878AD is an immersive living history experience in the Brooks Shopping Centre in Winchester, England. Described as “a multi-sensory museum experience with theatre, tech and play,” it was created through a partnership between Hampshire Cultural Trust, Ubisoft, and Sarner to utilise graphics from Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla (2020) as a backdrop for telling the story of the year 878 and King Alfred’s conflict against the Viking leader Guthrum. The experience simulates a street through Anglo-Saxon Winchester, and features live actors in Anglo-Saxon costume, artefacts from Hampshire Cultural Trust’s collections, and graphics, audio and gameplay footage from Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla to create an immersive living history venue. To further the experience, there is also a downloadable app that takes visitors on a walking tour around Winchester which offers minigames and utilises game graphics to help users engage with the city’s early medieval history.

I was initially brought on board as a freelance researcher to create a document detailing the costumes needed for the actors, and I now work at the venue as a member of the Front of House staff. I specialise in Early Medieval clothing and textiles, and the project managers emphasised their desire for fully authentic costumes to be featured in the experience. Our partners at Hampshire Wardrobe then created the outfits to my recommended specifications. This desire for full authenticity then created a juxtaposition between the completed costumes, and the graphics utilised within the space, as, while both the non-playable characters (NPCs) and player character’s designs are inspired by historical clothes, they are by no means completely accurate to this time period. Instead, the game designs use recognisable aspects of medievalism to appeal to the public’s perceived image of ‘The Dark Ages’, blending historical and fantasy elements to create a palatable view of the time.

The different ethnicities in Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla are emphasised by their character designs. As Raphaël Lacoste explains in The Art of Assassin’s Creed Valhalla (2020), “bold silhouettes and stances for each archetype are key to ensure immediate allegiance identification by the player in the game.”1 This is evident when comparing the two main opponents, the Vikings and the Anglo-Saxons. King Alfred’s character design surrounds him with crosses, both on his clothing, and in his vicinity. For example, at 1:00 into the teaser trailer for the game, Alfred wears vestment-like garments, his seat is carved with crosses, and a crucifix stands behind him. The emphasis on his Christianity serves to both play into the medievalist trope of the church dominating the medieval mind and sets him up as a foil to the pagan Viking characters, who are shown conducting rituals to their gods earlier in the trailer.

Similarly, the designs for the Scandinavian characters play into popular ideas of Vikings in modern media, particularly pushed by TV shows such as Vikings (2013 – 2020) and The Last Kingdom (2015 – 2022). These tropes include things like warpaint, braided hair, leather ‘armour’ and fur garments. Even Mehl Amundsen, a concept artist for the game, stated that “it was fun to push the concept of the Vikings, which is firmly grounded in the Dark Ages… the simpler versions of the Vikings still had to exude that ‘kick-ass’ mentality.”2 In modern public perception, Vikings are fierce, barbaric warriors, wearing leather lamellar and animal skins. This ideology stems right back to Wagner’s Die Walküre, a stage opera from 1856 that seemingly first fed into this standardised depiction of Vikings in most media now. Another aspect to this type of character design is the Rule of Cool, as Raphaël Lacoste explains: “We spend lots of time designing outfits to ensure that they make great rewards for our players.”3 Players want a gratifying, badass design for their characters in the game, and this then opens the door for more interpretive versions of unlockable clothing inspired by both historical and medievalist tropes.

Some have argued that this favouring of medievalist motifs harms the quality of the game. John Herman claimed that

“despite the game’s incredibly gorgeous visuals, specific aesthetic choices were made to amplify the gameplay experience rather than historical or religious accuracy… Ubisoft’s choices to revert it’s games from being museum-worthy recreations into wildly sensationalized ethnic and religious portrayals of characters and locations in AC: Valhalla diminish the level of historical accuracy seen in other Assassin’s Creed games.”4

While he is perhaps right that the player experience was placed above historical accuracy, it is perhaps somewhat ironic that these visuals are now indeed being utilised within a museum. But how do they work in the space?

878AD presents a mixture of concept art, gameplay footage, and NPC images around the space to add to the immersive nature of the experience. Life-size depictions of certain NPCs are positioned throughout, ranging from a musician to a nun. The figures help to ‘populate’ the town and tie into several of the scenes performed by our costumed actors. For example, we have a scene between a nun and a healer, and one between a lyre-playing storyteller and a weaver. The actors, in their historically accurate clothing, are juxtaposed against several backdrops from the game during their scenes, as well as their fantasy NPC counterparts, and this potentially has several different effects.

While some visitors, especially scholars, historical reenactors, or gamers, may perhaps find the inaccurate graphics jarring or confusing due to their sheer difference to the actor’s costumes, the graphics could be said to serve a useful purpose: attracting visitors via the ‘recognisable’ idea of a medieval persona, before our actors and artefacts introduce them to a more realistic portrayal. This could perhaps help bridge the gap between public conceptions of the medieval world and of historical clothing, and the museum education side of the story. While some members of the public may not even necessarily notice that there is a real difference between the live costumes and the game designs, it may subconsciously help to introduce realistic medieval silhouettes to the public consciousness and detract from the idea that the ‘Dark Ages’ were backwards and barbaric, a common medievalist trope.

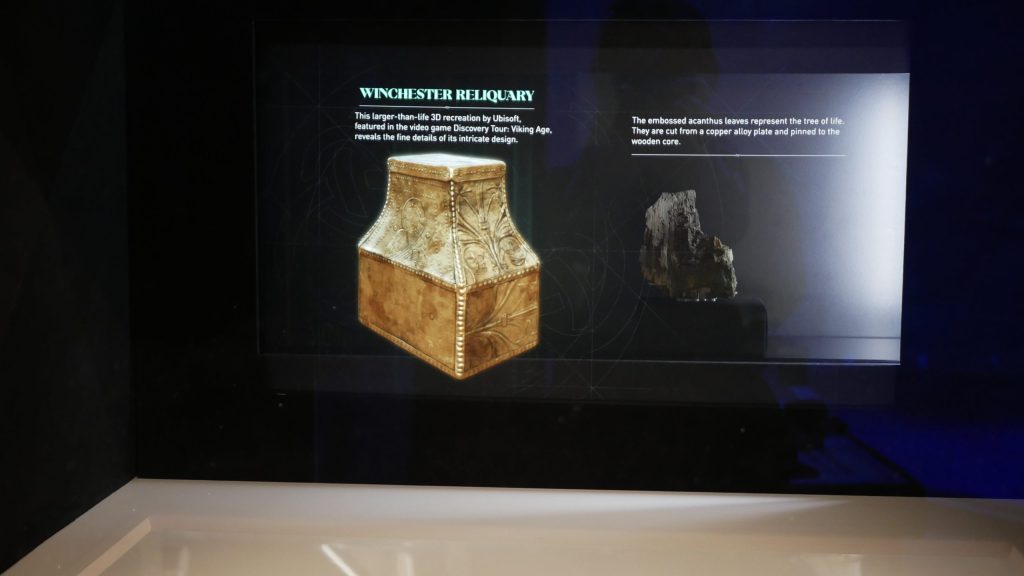

878AD also uses graphics from Assassin’s Creed Discovery Tour: Viking Age (2021) to further public education. One of the quests in the Discovery Tour has players retrieve a reliquary, and while the in-game version is huge by comparison, it is an otherwise wholly faithful depiction of the real Winchester Reliquary, the star object of the 878AD experience. The museum utilises the 3D model of this object by displaying in alongside the actual object in an informative video about the item. As the reliquary is now fragmentary and displayed in two halves, the 3D model is vital for presenting the object as it originally was and allows for a fully dimensional view of the item. It is also a very recognisable object to those who have played through the Discovery Tour itself, helping to pique interest in learning more about the period and the items on display by seeing the object from the game in real life.

To conclude, 878AD uses the graphics from Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla in a variety of ways. The NPC artworks serve as palatable, recognisable ‘medieval people’ to attract visitors through their preconceived notions of Vikings in modern media, whilst also populating the reconstructed town. 3D models of objects like the reliquary help to further the public’s understanding of them by presenting them as they originally would have looked. Lastly, they serve as a link between the fantasy gameplay elements of Valhalla, and the realistic depictions of characters through costumed live actors to bring to life the historical background of the year 878.

Katie Newell works for Hampshire Cultural Trust in Winchester, including at 878AD, an immersive museum experience that uses graphics and media from Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla to bring to life King Alfred’s Winchester and the Anglo-Saxon period. In her free time, she is also a living historian and reenactor, specialising in the Early Middle Ages, and her work in this area can be found on Instagram via @skadi.blodauga. She graduated from the University of Winchester in 2022, where she attained a BA in Medieval History with First Class Honours.

References

- Raphaël Lacoste in Ubisoft, The Art of Assassin’s Creed Valhalla (Milwaukie: Dark Horse Books, 2020). ↩︎

- Even Mehl Amundsen in Ubisoft, The Art of Assassin’s Creed Valhalla (Milwaukie: Dark Horse Books, 2020), p. 49. ↩︎

- Lacoste in Ubisoft, The Art of Assassin’s Creed Valhalla (Milwaukie: Dark Horse Books, 2020), p. 17. ↩︎

- John Herman, “A Review of Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla’s Sensationalized History.” Gamevironments 14 (2021): 257-262. ↩︎