The study of history in digital games related to memory culture often focuses on games that directly address a specific historical period or topic with the goal of increasing players’ understanding and knowledge.1 This can range from simple educational goals, to creating emotional connections to the past, to ideological and moral goals. Much less often, however, do researchers look at the influence of memory culture itself on the development of entertainment games. In his book Geschichte und Erinnerung in Computerspielen (History and Memory in Computer Games), Nico Nolden aptly describes this influence as a historical feedback loop (“zeitgeschichtliche Rückkoppelung”). He argues that every game developer is tapping into their own historical understanding while designing rules, stories and worlds, acting as an intermediary to convey contemporary understandings of history.2

Looking at fantasy games, especially Western fantasy games, the most obvious aspect of this feedback loop is popular historical images of medieval Europe that influence their development. But in addition to this direct contemporary understanding of the past, more subtle influences can also be found. As an example, Nolden mentions the strategy game Medieval 2, whose faction design is based on an Anglo-Saxon understanding of the nation-state and thus interprets the federal nature of the Holy Roman Empire as a weakness.3 The contemporary socio-political context of the game’s creators thus influenced their view and design of medieval forms of governance and this allows us to understand how they specifically remember the Middle Ages.

But not every game communicates its historical inspiration as clearly as the previous example. Some merely adapt it into a highly fictional setting, which still offers researchers the opportunity to analyze how the culture of memory itself influences the creation of the games themselves. In this short article, I will analyze the Gothic and ELEX role-playing game series by the German studio Piranha Bytes as such an example.

Mining in Gothic and the Ruhr Area

Piranha Bytes was founded in 1997 in Bochum, a city in the German Ruhr area, the former center of the German coal and steel industry.4 During its 26 years of existence, the studio has worked on three fantasy and science-fiction roleplaying series: Gothic, Risen and ELEX. The first two games of the Gothic series in particular are considered cult classics in the German video gaming scene, with significant fan bases in Poland and Russia as well. Since the release of the first Gothic in 2001, the public discourse surrounding these games has been dominated by one elusive aspect: the so-called “Ruhrpott-Charme”, a certain flair that is specifically attributed to the inhabitants of the place where the games are created, the Ruhr area.5

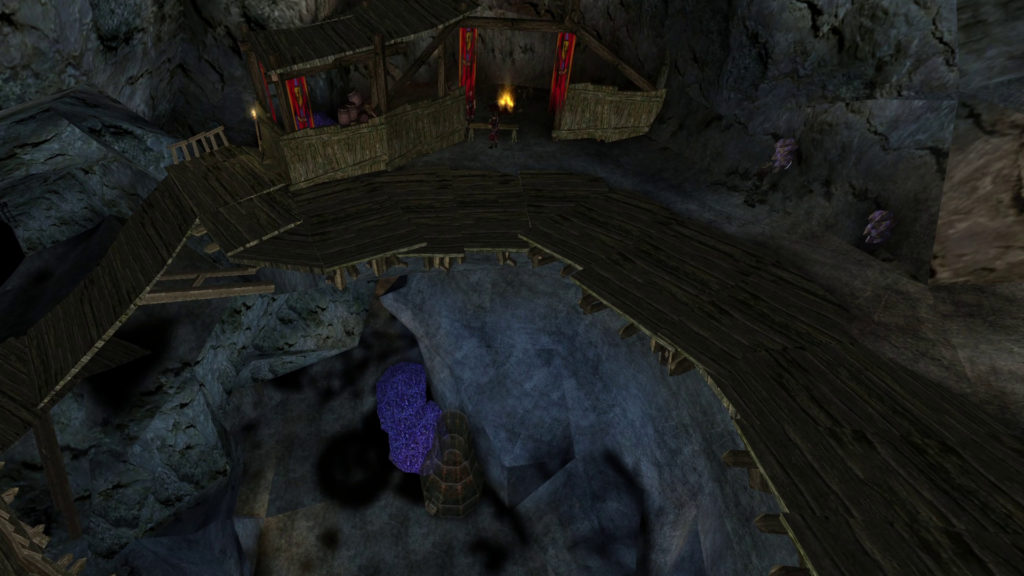

This flair has mainly influenced the way the characters in Piranha Bytes’ games act and talk, which is defined by direct pragmatism and leaves almost no room for glory and great pathos, something that is also attributed to the actual inhabitants of the Ruhr area. But this is not the only connection to the industrial region in the west of Germany: The first Gothic is set in a prison colony. The prisoners are tasked with mining valuable ore for the king’s war effort. However, an uprising leads to the prisoners taking over the colony and blackmailing the king with their control over the ore. The player character enters this ecosystem and must navigate a society and economy based solely on access to (and mining of) ore, with the ultimate goal of escaping the prison. There are many parallels to German history here, as the Ruhr was central to the war effort in both World War I and World War II, with millions of people forced to work in the mines and factories of the Ruhr. The Ruhr was also the site of armed unrest, such as the short-lived uprising of the so-called Ruhr Red Army against the Kapp Putsch, a right-wing attempt to overthrow the elected government of the Weimar Republic.

In Gothic 2, the situation has changed. The prison colony is no more, and the ore mines are almost depleted. Most of the characters from the previous game are refugees, confused by the sudden collapse of the colony and looking for new ways to earn a living and ensure their survival.

Between the first and second Gothic games, the importance of ore to the game’s characters changed at a different pace. While some still rely on it, others try to move on. Though not exactly the same, this shows remarkable similarities to the development of the real Ruhr area. Its industrial dominance began to decline with the coal and steel crises in the late 1950s. West Germany then began a decades-long process of slow deindustrialization to avoid the sudden collapse of one of the country’s most important employment sectors. From the second half of the 20th century onwards, the Ruhr area was and still is synonymous with the slow death of industrial culture, coupled with strong struggles against this decline by unions and the working class in general.6 The developers of Gothic live in and around this development, and while Gothic is not specifically about the deindustrialization of the Ruhr, its influence is evident in the series’ focus on mining and its economic importance to the world and people of the game.

The Ruhr’s Post-Industrial-Era in Elex

In Piranha Bytes’ next RPG series, Risen, mines and caves returned as a common design element. With this series, however, the studio moved away from dark, medieval-inspired worlds to a fantasy pirate world. That is, until the development of ELEX, which is set in a science-fantasy world where technological advances and magic coexist. After a catastrophic event, modern society as we know it has collapsed and out of its ashes several factions have emerged. Some simply use whatever they can find to survive, others worship the old technology as sacred and yet a third faction has abandoned all technology and is using magical artifacts to restore the planet’s nature.

In a way, the world of ELEX feels like a fantastical reflection of the development that the Ruhr area has slowly undergone since the 1990s. Coal mining has been completely abandoned and steel production has been reduced. Old industrial factories and plants are either abandoned, slowly becoming overgrown, or have been converted into cultural centers. Here art festivals are held and a new middle class sips wine while listening to concerts, nostalgically remembering the struggle of their ancestors in the mines, as Stefan Berger puts it not without cynicism in his attempt to define the identity of the Ruhr area historically in his article “Was ist das Ruhrgebiet?” (“What is the Ruhr area?”).7

While ELEX is set in a dystopian world full of warlords and warring factions, it is also the beginning of a new world where its people are striving for a new beginning. Fittingly, it also contains the most direct references to the Ruhr area, with an old coal mine tower modeled after the UNESCO World Heritage Site Zeche Zollverein in Essen. Similarly, ELEX 2 features a real photo of the same tower as a collectible (among other similar photos), creating a direct link between the Ruhr area and the ELEX game world.

From the thriving mining valley in Gothic to its collapse in Gothic 2 to the post-industrial wasteland in ELEX and ELEX 2, the developers at Piranha Bytes have incorporated not only their own lived experience but also the collective memory of the industrial culture of the Ruhr region into their games. Especially for games that are primarily commercial entertainment products, this cultural specificity is remarkable and invites further research. The production of games is deeply rooted in a globalized market and consumer culture, which has led to an international homogenization of themes, especially in the case of entertainment games with a need for high sales figures. In contrast, Piranha Bytes’ games show how important and interesting the inclusion of local cultures and their collective memory can be.

[*A big thanks to Jennifer Pankratz from Piranha Bytes for talking with me about this topic and helping me tracing the links between Gothic, Risen, Elex and the Ruhr area.]

Rüdiger Brandis studied history, literature, cultural anthropology and game development. He worked at the University of Göttingen and the TH Cologne in the field of historical theory and game studies before moving into the game industry as a game designer and producer. He currently works as Lead Producer for Flying Sheep Studios and also founded the studio Achtung Autobahn Studios, which aims to specialise in the development of social-realistic games. He is currently doing his PhD on the influence of historical theory on the development of digital historical games at the Chair for Theory and Methods of Historical Studies at the University of Göttingen. (more here)

Notes

- A few examples include: Bury Me, My Love (2017), Through the Darkest of Times (2020) & Blackhaven (2021). The German foundation Stiftung Digitale Spielekultur (Foundation for Digital Games Culture) also works continuously on a database containing and discussing games with themes related to memory culture. ↩︎

- Cf. Nolden, Nico (2019): Geschichte und Erinnerung in Computerspielen, pp. 192-210. ↩︎

- Cf. ibid., p. 195. ↩︎

- Cf. Piranha Bytes: Company. https://www.piranha-bytes.com/index.php?navtarget=2&lang=en (accessed 10.08.2023) ↩︎

- Cf. Halley, Dimitrey (2016): ELEX – Echte Revolution oder doch nur Gothic? https://www.gamestar.de/artikel/ELEX-echte-evolution-oder-doch-nur-Gothic,3305482.html#top ↩︎

- Cf. Brüggemeier, Franz-Josef (2021): Das Zeitalter der Kohle in Europa, 1750 bis heute, pp. 22-24. ↩︎

- Cf. Berger, Stefan (2021): Was ist das Ruhrgebiet?, p.101. ↩︎

References

Berger, Stefan (2021): Was ist das Ruhrgebiet? Eine historische Standortbestimmung. In: Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung (Ed.): Abschied von der Kohle. Struktur- und Kulturwandel im Ruhrgebiet und in der Lausitz. Bonn, pp. 90-103.

Brüggemeier, Franz-Josef (2021): Das Zeitalter der Kohle in Europa, 1750 bis heute. In: Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung (Ed.): Abschied von der Kohle. Struktur- und Kulturwandel im Ruhrgebiet und in der Lausitz. Bonn, pp. 22-24.

Halley, Dimitry (2016): ELEX – Echte Revolution oder doch nur Gothic? Online: https://www.gamestar.de/artikel/ELEX-echte-evolution-oder-doch-nur-Gothic,3305482.html#top (accessed 10.08.2023).

Nolden, Nico (2019): Geschichte und Erinnerung in Computerspielen. Erinnerungskulturelle Wissenssysteme. Oldenburg.

Stiftung Digitale Spielekultur (ongoing): Datenbank: Games und Erinnerungskultur. Online: https://www.stiftung-digitale-spielekultur.de/games-erinnerungskultur/ (accessed 10.08.2023).

Games

Gothic (Shoebox 2001, O: Piranha Bytes)

Gothic 2 (JoWood 2002, O: Piranha Bytes)

ELEX (THQ Nordic 2017, O: Piranha Bytes)

ELEX 2 (THQ Nordic 2022, O: Piranha Bytes)

Medieval 2; Total War (Sega 2006, O: Creative Assembly)

Bury Me, My Love (Plug in Digital 2017, O: The Pixel Hunt)

Through the Darkest of Times (HandyGames 2020, O: Paintbucket Studios)

Blackhaven (Historiated 2021, O: Historiated)