The landscape and implications of sandboxes, modding and user-generated content in historical games

The evolution of game modding

As video games grew in popularity, their developing player communities quickly took advantage of their mutable nature, particularly on PC platforms. Especially early on, games were often installed with non-obfuscated code and assets which could be easily modified or swapped. This led to the practice of ‘modding’, whereby players with relevant technical and creative skills could modify games, creating everything from small balance, visual, and quality of life tweaks, all the way to entirely new games and genres, effectively using the original game as an engine and creativity outlet.

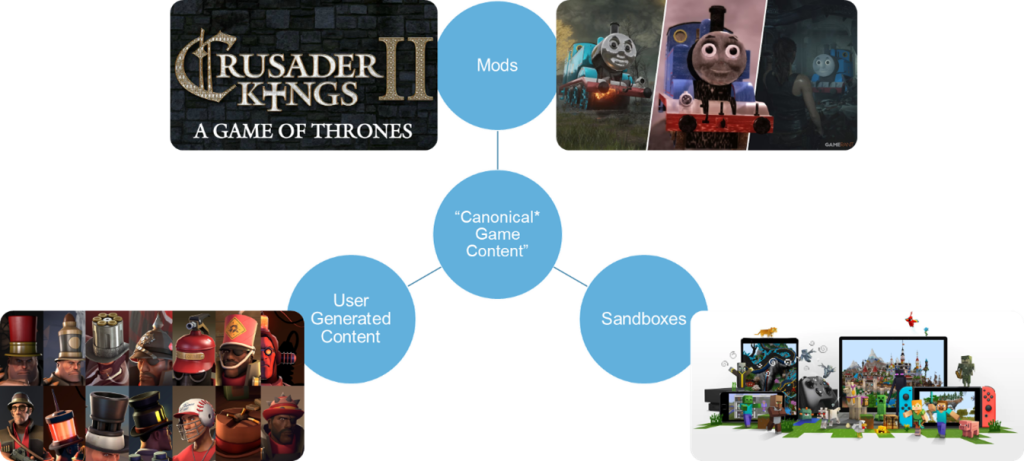

Many developers embraced this practice, publishing their games with modding support. Conversely, some publishers actively discouraged modding, citing reasons that ranged from the technical difficulty of using the game’s development tools, to cheat prevention. Notably, the lack of modding support coincided with the adoption of the downloadable content (DLC) and servitisation business models which now dominate the industry. Games ship with a base amount of content, which is expected to be increased through future updates, DLC and expansions. Depending on the game, these updates can also feature unofficial content, either from external sources through mods or user-generated content, or internally due to a sandbox design or in-game content creation tools (Figure 1). The distinction between these types of content is primarily along the lines of creative freedom and moderation processes. Mods made with official or unofficial development tools tend to be less moderated but often unlimited in terms of IP or scope, while those made in-game and distributed (and monetised) within the game (or more appropriately ‘platform’) are usually better moderated and smaller in scope and have to abide by terms of service. Sandbox content is made exclusively in-game and is mostly an expression of creativity using in-game mechanics. This limits the scope of potential creations to what is available in-game, but this can often be subverted.

There is strong evidence to demonstrate that games that support user-generated content, either with inbuilt tools or with modding support, have considerably longer-lasting communities – often with comparatively little post-release support from the developers. Indeed, some of the most influential and genre-defining games originated from mods (Postigo, 2007; Winnerling, 2014). Examples abound, and include games such as Counter-Strike, which began life as a Half-Life mod; the Warcraft 3 mod Defence of the Ancients, later to become DOTA and popularise the MOBA genre; and several ARMA mods, that used the military simulation game to foster genres such as “Open-World Survival” with DayZ, and “Battle Royale” with PUBG: Battlegrounds.

There is a discernible trend where, prior to the rise of accessible game engines such as Unity 3D, games that provided modding support were the ideal incubators for novel game designs and creators. This is the trajectory that the now ubiquitous Unreal Engine trailblazed, transitioning from a game to a game engine. This is the opposite of the originally equally moddable id Tech engine, of Doom and Quake engine fame, which followed a different path, being licensed and further developed for the Call of Duty series, and forking into the very successful, and extremely moddable, Source engine.

Player modding practices

While it can be supported that mods have been a net positive for the games industry and gamers, they have raised significant implications and challenges for how user-generated content is handled in the gaming landscape. Mods encourage creativity but also enable the promotion of potentially contentious and controversial views (Pfister & Tschiggerl, 2020). This is a similar challenge to that faced by the GLAM (Galleries, Libraries and Museums) industry at large with the increasing popularity of participatory visitor experiences that enable visitor interpretations.

Games face the same challenge; however, here the challenge is exacerbated by the existence of comparatively large pre-existing audiences and an inherent difficulty in moderating mod content. This has the effect that moddable games can act as platforms for the dissemination of extremist ideas, misappropriation and harmful revisionism, and possibly as avenues of radicalisation (Andrews, 2022).

This is particularly evident in historical games, which by their nature already adopt and represent a particular historical perspective and narrative (Apperley, 2007; Chapman 2016). Games that draw on real-world events inevitably run into the challenge of conflicting narratives (Apperley, 2013). Often these games also endow the player with the power and agency to change the course of events and in effect, rewrite history (Pennington, 2022).

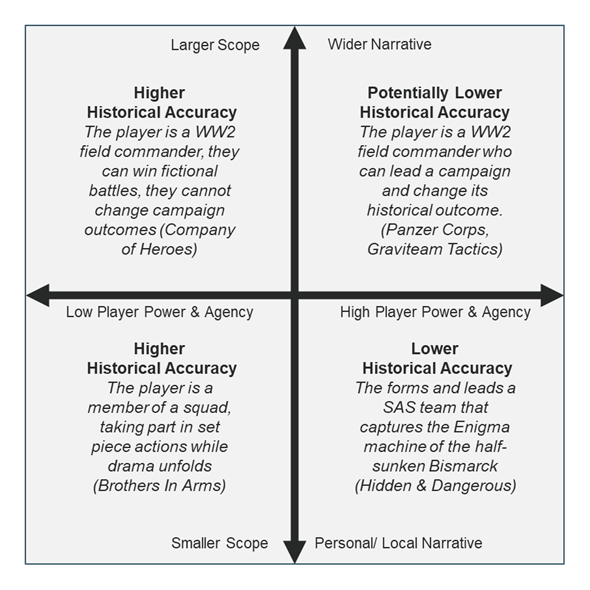

This demonstrates a tension between re-enactment and a mutable sandbox. Arguably, a historical game that maintains a historical narrative will struggle to encompass a larger scope and provide extensive player agency. And it may have to constrain and shape its narrative to given historical facts. On the other hand, a historical game that allows significant deviation from established fact may struggle to retain historical legitimacy, while also creating an opening for players to express differing views.

Case study: Hearts of Iron 4

A notable example is the Hearts of Iron strategy game series (HoI), which places the player in the role of the leader of a nation during World War II. What sets these games apart from the many others that depict this setting is that HoI aims to be a historical sandbox, giving players a starting date with a “historically accurate state of the world” at that time (by default January 1936), and then the freedom to deviate. While a relatively deep simulation, HoI’s permission is still an illusion, as the courses the players can take are somewhat limited by HoI’s National Focus system. In most cases, the unmodded (or ‘vanilla’) game allows players to follow a historical national focus, or deviate at key points to follow an alternative path, usually along ideological lines. While many players stick to historical paths, a not-insignificant number of players systematically conduct playthroughs where they intentionally pick alternative options. The HoI developers release semi-regular “Telemetry” summaries that provide data-driven insights into the choices of the player base.

There is a very interesting tension between re-enacting history and a mutable historical sandbox. Arguably, a historical game that sticks to a historical narrative will struggle to encompass a strategic scope and provide player agency such as HoI does. It may have to constrain and weave its narrative according to given historical facts. On the other hand, a historical game that allows significant deviation from established fact may struggle to retain historical legitimacy, while also creating an opening for players to express differing views.

However, HoI is extremely moddable, and its community has created innumerable mods that range from minor tweaks to total conversions for fantasy and science fiction settings. Thus, it has also fermented a significant number of mods that express or implement a variety of controversial content, including examples of nationalist extremism and negationist historical revisionism. This has several negative knock-on effects, both in an immediate practical sense to communities and developers, but also more longitudinally by amplifying the increasingly evident negative aspects of online culture on society.

Case Study: The ARMA series

The ARMA series by Bohemia Interactive is another strong example of a game that has surpassed its original intent of being a sandbox for combined arms military gaming. Its modability enabled creative players to produce numerous mods that add an incredible amount of historical, real-world and science-fiction factions and their equipment.

Like HoI, ARMA‘s basis in contemporary conflict has been fertile ground for a variety of views to be expressed (Lakomy, 2019; Squire, 2024) and its fidelity has led to gameplay footage being problematically publicised (knowingly and by accident) as real-world conflict footage1 – which prompted an official response.2

With published ARMA 3 mods numbering in the hundreds of thousands, and communities that have formed around Military Simulation (MilSim) roleplay, which often focuses on particular conflicts and re-enactments, it is not hard to see how the ARMA sandbox can be misappropriated, despite the efforts of the developer to temper this trend directly.3

The negative implications of modding and user-generated content

Despite the many positives that modding has for the longevity of a game and the creative expression of its users, we can conclude that there is a negative side as well. Games, like any form of media, can attract unintended audiences, who appropriate them and utilise them as platforms for inappropriate purposes, taking advantage of their large audiences. Depending on the content dissemination model the game developers or publishers employ, they can lose any control or moderation of the game’s content and direction, letting its nature and intent be twisted. This leads to the question of what can be done to combat such misappropriation. The answer to this is complex, and it must also be noted that it exists regardless of a game’s support for user-generated content. Mods do not cause misappropriation, but they can enable it.

Considering a framework for historical game design

A systematic analysis of games gives rise to an emergent multi-dimensional framework that considers, among other characteristics, a game’s adherence to historicity, historical narrative flexibility, player agency, mod-ability, popularity and community. The aim of this framework aims to help conceptualise, communicate and further understand how these characteristics can occur and what effects they can have, such as attracting unintended audiences and inadvertently becoming platforms for controversial content, which have severe negative knock-on effects, both for communities and developers, but also more longitudinally by amplifying the increasingly evident negative aspects of online cultures (Wells et al., 2023).

For historical games, player agency is a key factor. Such games draw on real-world events and have to deal with conflicting narratives, while player agency introduces opportunities for the participant trajectory to deviate from the ‘canonical’ narrative. This is not necessarily a bad thing. In the context of historical game design, there is a tension between agency and re-enactment – at least along one dimension. Simplistically, the higher the player agency in a game, the lower the historical accuracy will be as the player can deviate from established history. Considering this along one dimension is too reductive. A second dimension to consider could be the ‘scope’ of the game’s context and narrative.

Currently, the work-in-progress Historical Game Design Framework considers two dimensions (Figure 2), player power and agency within a game, and the scope of the game’s context, setting and narrative. Historical games can be plotted on this framework in terms of their “perceived historical accuracy” to observers. Other potential dimensions could be “realism vs. fantasy”, or several cultural perspectives. Going forward, this research aims to elicit thoughts on the implications of user-generated content in the already challenging space of historical games, through the discussion of case studies and the co-creation of a framework that disambiguates the nature and effects of sandbox and moddable historical games.

Dr Dimitrios Darzentas is a lecturer in the School of Computing, Engineering, and the Built Environment (SCEBE) at Edinburgh Napier University and formerly a multidisciplinary Research Fellow in the Mixed Reality Lab of the University of Nottingham. His work is situated at an intersection between Human-Computer Interaction and Design with a broad scope including Mixed Reality Technologies, Experience Design, Digital Storytelling and Cultural Heritage, Service Design, Playful Interactions, Wellbeing, Sustainability and Political Engagement, among others. His current research interests include Hybrid Physical/Digital Experiences, Meaningful Interactions, the Socio-Political and Cultural Heritage aspects of Gaming, virtual production workflows for interactive experiences, and harnessing Data (AI)-Supported Creativity.

References

Andrews, S. (2022, February 17). Understanding Attitudes to Extremism in Gaming Communities. GNET. https://gnet-research.org/2022/02/17/understanding-attitudes-to-extremism-in-gaming-communities/

Apperley, T. (2007). “Virtual Unaustralia: Videogames and

Australia’s Colonial History”. Proceedings of the Cultural Studies

Association of Australasia Conference 2006: 1–23.

http://www.academia.edu/385987/Virtual_UnAustralia_Videogame

s_and_Australias_colonial_history.

Apperley, T. (2013). “Modding the Historians’ Code: Historical

Verisimilitude and the Counterfactual Imagination” in Playing with

the Past: Digital Games and the Simulation of History edited by

Matthew Kappell & Andrew B. R. Elliott, 185–98. London:

Bloomsbury.

Chapman, A. (2016). Digital Games as History: How videogames represent the past and offer access to historical practice. Routledge.

Lakomy, M. (2019). Let’s Play a Video Game: Jihadi Propaganda in the World of Electronic Entertainment. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 42(4), 383–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2017.1385903

Pennington, M. J. (2022). Authentic-lite rhetoric: The curation of historical interpretations in ‘Hearts of Iron IV’ [Phd, Bath Spa University]. http://researchspace.bathspa.ac.uk/14679/

Pfister, E., & Tschiggerl, M. (2020). “The Führer’s facial hair and name can also be reinstated in the virtual world” Taboos, Authenticity and the Second World War in digital game [Application/pdf]. https://doi.org/10.24451/ARBOR.15839

Postigo, H. (2007). Of Mods and Modders: Chasing Down the Value of Fan-Based Digital Game Modifications. Games and Culture, 2(4), 300–313. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412007307955

Squire, C. S., Kurt. (2024). Introduction to Videogames and the Extremist Ecosystem. In Gaming and Extremism. Routledge.

Wells, G., Romhanyi, A., Reitman, J. G., Gardner, R., Squire, K., & Steinkuehler, C. (2023). Right-Wing Extremism in Mainstream Games: A Review of the Literature. Games and Culture, 15554120231167214. https://doi.org/10.1177/15554120231167214

Winnerling, T. (2014). The Eternal Recurrence of All Bits: How Historicizing Video Game Series Transform Factual History into Affective Historicity. Eludamos: Journal for Computer Game Culture, 8(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.7557/23.6432