As both a game developer and a medieval historian, each of my interests informs the other. In this post, I’m going to talk you through some ways I approach putting medieval elements in games and think about why they’re there.

The process I use is based on thinking about medieval ideas as a sort of curated collection in a game. Other starting points exist, usually thinking about the accuracy of a whole game (how close it is to precisely representing reality) or its authenticity (how much it feels to the player like it’s representing the past as they imagine it). Often, though, rather than assessing a whole game for accuracy or authenticity, we’re often better focusing on individual elements and asking where they come from and why they’re used. No game is totally accurate, and accuracy in one area of a game doesn’t counteract inaccuracy in another: the effect on the player of having an accurate or inaccurate 3D medieval dress model and the effect of having an accurate or inaccurate portrayal of how people historically interacted with faith and social mores are very different.

This idea is particularly important when considering fantasy games. Most history, and especially medieval history in gaming, isn’t found in games that are trying to be direct simulations of the medieval past, but in elements that we associate with historical cultures turning up in otherwise unrealistic games or settings. We’ve no evidence that people directly assume that their games – realistic or not – are giving them a complete view of history. Indeed, studies in education settings very much indicate that people don’t make that assumption.1 Historical ideas embedded in games are nonetheless powerful because they form part of a discussion space between the past, the fantastic, and the present – one especially important when it comes to ideas about identity or nation that are often rooted in our understanding of the medieval.2 History is crucial in that space because it adds both possibilities (by showing us different worlds) and anchors (by providing information about where our current world comes from). It’s part of the stories we tell about who we are. That isn’t always a literal understanding, but it is one that matters to people, for better and worse.

The Exile Princes and Curated Medievalisms

The concept of a curation process is also useful from a designer’s perspective, and enables better collaboration between historians and developers. By understanding more consciously where certain elements of a game have come from and why they’re there, we can empower ourselves creatively by better knowing what to look for, and consider what elements of the past might have been left out when informing the historical inspiration for a game’s design.

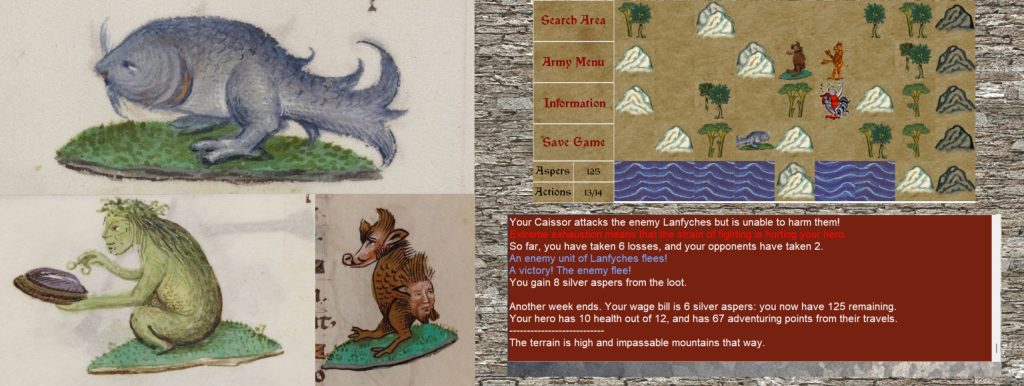

To give you an idea of how this works, let’s take a tour through my own latest project. The Exile Princes is a strategic role-playing computer game, with a text readout and simple graphics. The player controls their character and a small ‘warband’ or army of troops that can move around a tile-based map and engage in turn-based combat and decision-making events. Cities on the map provide central hubs in the game: the game’s ultimate objective is to control all the cities, and they function as places for recruitment, quest-giving, healing, and various ways of increasing one’s influence through politics, elite connections, and military might. Beyond the cities, small bands of heavily settled farmland give way to larger areas of forest and plains which include some foes but also searchable tiles that can contain farms, woodcutters, charcoal burners, and a variety of other medieval-style people going about their business.

The most obvious medievalism in the game is in the art. Images for the game’s tile-type graphics were produced with reference to real manuscripts, especially from the British Library and the Bodleian Library, plus some tweaks, edits, and reinterpretations by myself.

Reinterpreting medieval art was an important part of the development process. A lot of the figures in medieval marginalia that were used were strange or demonic in some way – a fish with legs, clawed imps, a bipedal boar. Working out how those creatures would fit into my pseudo-medieval setting was an interesting process: some of them became ‘naturalised’ as features of the world the player would inhabit, whereas others kept a more demonic, external position.

This distinction isn’t absent from medieval European thinking: strange and marvellous creatures or peoples described in travelogues and bestiaries are often understood to be miracles of the real world, often with an allegorical connection to showing the nature of creation, as opposed to being directly divine or infernal. The game draws explicitly on some of these imaginaries of distant and miraculous parts of the world, for example in its use of blemmyae, one of the ‘monstrous races’ of headless men with eyes and a gaping mouth on their chest. It also has its own creations, with legged fishes (lanfych as I named them in the game) taken from a piece of medieval art and then fleshed out into the sort of creature one might find in a medieval bestiary as best as I was able. The more naturalistic approach to for example the lanfyches means the player can do things like find a young one and raise it as a pet, an option not available with the more demonically-framed creatures: mechanically as well as visually, the interpretations I built around different bits of marginalia affect the player’s experience of the game world.

One thing I’d have liked to have done (but didn’t for lack of time) was to explore those bestiary-style understandings more: there’s a tonal tension between modern games’ scientistic depictions of animals, which tend to a pseudo-scientific tone to go with the necessary numeric stat comparisons, and the more fantastical and allegorical understandings of creatures we see in medieval texts. Thinking more about how some of these creatures are understood symbolically by the people of the game’s setting would have been a nice addition to what is already present in the game.

Another way that medievalisms give the game flavour is through various direct references to medieval texts. For example, the difficulty settings are all named after particular medieval figures. John Mandeville, the apocryphal author of a wildly popular medieval travelogue, is the figurehead for the sandbox mode where the player can’t die – because it’s all made up anyway. Vis, protagonist of the Persian & Georgian tales of Vis and Ramin, is the easy mode. Moriaen, the Ethiopian knight of the Round Table found in Dutch romance, is the standard difficulty. Flea on a Drum, a thief from the Chinese novel Outlaws of the Marsh, appropriately figureheads the roguelike mode. Finally, for the hardest difficulty there is Silence, from the Roman de Silence, who is born female but lives as a man and has nature and nurture argue over their ultimate fate, riffing on the concept of nature being against the player character.

These elements are there on a surface level to give some light flavour, but they also perform two other important functions. Firstly, they bring the game more clearly into dialogue with medieval texts, making it less ‘generic fantasy’ and signalling its anchoring to those traditions. Secondly, they illustrate the kind of medieval world this game has: one that takes inspiration from a lot of different parts of the real medieval Eurasian world, with a colourful array of characters and some quirky creatures and plotlines. This sets the game apart both from more purely aesthetic medievalisms that lack such a direct connection to their source material, such as those in modern fantasy games like Baldur’s Gate 3 or Dragon Age: Veilguard, and also from more ‘gritty’ medievalisms seen in games that sell themselves on a sense of violent verisimilitude, like Kingdom Come: Deliverance, Mount & Blade, or Dragon Age: Origins.

Curating Player Actions

Historical references in games, however, aren’t just about visual and textual signalling. What you can do and how you can do it are also important parts of the interactions between a game and the imagined pasts it’s trying to evoke.

In The Exile Princes, aspects of the core gameplay were designed by thinking about simple but historically-minded ways to model such processes. When controlling a city later in the game, the player has a lot less control than might be the norm in some strategy games: rather than a range of spreadsheet-like systems to implement fine control of a place, the player simply gets to say yes or no to certain suggestions made by a city’s petitioners, officials, and courtiers. The intention of this was to keep the role-playing element at the forefront and put the player into the role of a ruler whose duties included war, maintaining personal connections, and making judgements, but who did not have access to the kind of statistics and data that define modern governance.

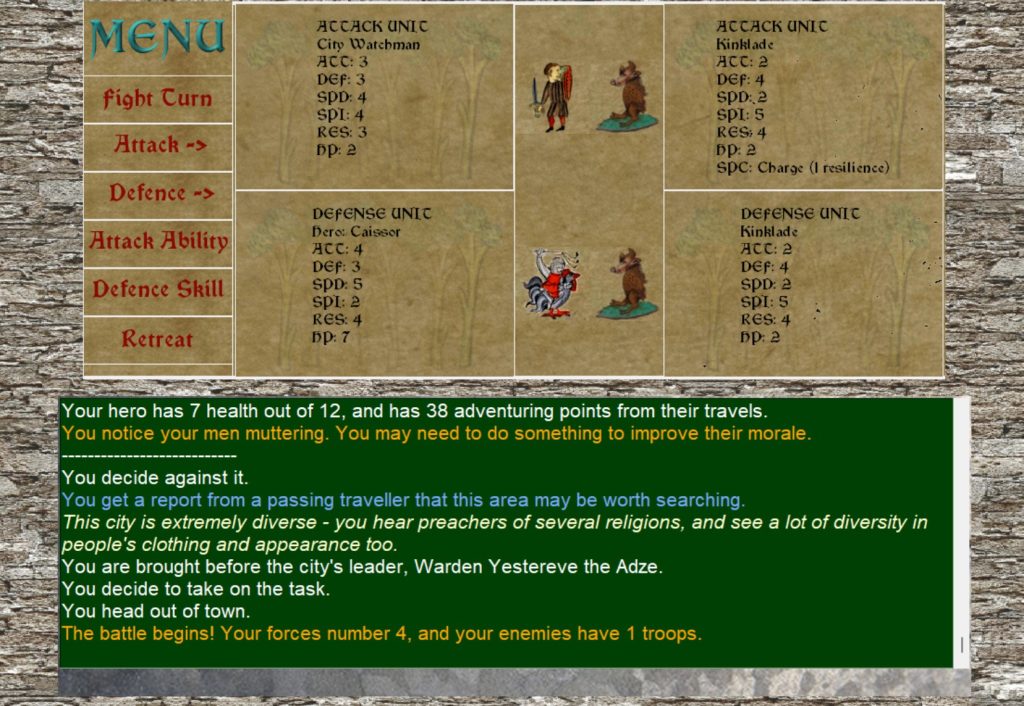

Conversely, the battle system is extremely abstracted. The player has one ‘attack’ and one ‘defence’ unit at any given time, and the enemy attack unit attacks your defence unit and vice versa, with an exhaustion mechanic that means it’s helpful to swap out units as they get tired. Needless to say, real battles do not in any sense work this way. The decision made here was a mixture of ludic and narrative concerns: I wanted to keep the battles on a simple system that kept with the low graphics and input complexity of the game, and I wanted to keep them relatively quick to keep the focus on the story, whilst still having enough mechanical complexity to provide a challenge.

There are elements of this, however, that are designed to help reflect elements of medieval literature as opposed to medieval reality: only having two units ‘in play’ at a time centres the player and their companions in how battles unfold, enabling me to keep a wider army system whilst still having strong roles for characters, including moments where characters’ traits such as recklessness can affect strategy. When we think about historical references in games, we should always remember that reflecting historical imaginaries and realities are both ways of bringing history into gameplay – in some cases they’re clearly different, but at other times we might find them hard to distinguish.

Conclusions

Overall, understanding these medieval references, processes, and elements, and how they’re encoded, helps us make better historical games. The goal isn’t a single holy grail of ‘an accurate game’, but rather of taking a wider array of different possible approaches to the past. That can give players more ways to understand how societies can work – deepening that possibility space and making it more meaningful – and it can give developers more ways of building interesting historical elements into their games and gameplay.

James Baillie is a historian at the Austrian Academy of Sciences’ Institute for Iranian Studies, specialising in the history of the medieval Caucasus region and in the ways that our understanding of history is influenced by computer systems and data structures. His research has included several pieces on computer games, and he is the convenor of the Coding Medieval Worlds workshop series which connects historians and game developers. He is also an active game developer and chair of the Exilian creative projects and indie developers’ community: his most recent title, the medieval-fantasy RPG The Exile Princes, was released in December 2024, and his other games include the medieval wetland survival-adventure game Fenlander. You can find him on BlueSky (@jubalbarca.bsky.social) and Mastodon (@JubalBarca@scholar.social).

Works Cited

- Kevin O’Neill and Bill Feenstra, “‘Honestly, I Would Stick with the Books’: Young Adults’ Ideas About a Videogame as a Source of Historical Knowledge” Game Studies 16.2, (2016), https://gamestudies.org/1602/articles/oneilfeenstra ↩︎

- Richard Utz, “The Great Complicity: Medievalism and Nationalism”, Medievalists.net (2022) https://www.medievalists.net/2022/01/medievalism-and-nationalism/ ↩︎