Classical video games are not immune to the ailment most video games suffer from: at best erasing and at worst denigrating and/or abusing women. This becomes increasingly problematic when history is concerned not just because it legitimizes the representations included in the games through association with historical events and – it is present in a historical game, therefore it must be ‘true’ – but also because it risks rehashing a version of History with a capital ‘H’, a biased, selective and exclusionary version of events usually told from the perspective of those with power. Furthermore, for a significant portion of the player base, this is likely to be the first contact with the historical events, settings and characters depicted in these games, thus shaping further perspectives on history, and circumventing critical engagement.

The main challenge of historical games, classical games included (games which use the Ancient World and Greek and Roman mythology as their setting) is balancing entertainment value, player agency and player expectations, with historical accuracy and authenticity. Historical accuracy is often cited to protest to the inclusion of (too many) women in classical games, particularly as most focus on warfare and politics, areas of the public sphere where women have been less visible and prominent in historical accounts. This, of course, ignores current critical approaches to the authorship and biases inherent in these same historical accounts and risks perpetuating cultural and gender stereotypes, structures of oppression and prejudice. This argument also proves to be selective: historical inaccuracies and fallacies in everything but gender are more easily forgotten and forgiven, as demonstrated in Women in Classical Video Games, edited by Jane Draycott and Kate Cook (Bloomsbury, 2022). This makes the volume an important and timely collection of perspectives brought together to critically discuss and question the representation of women in classical video games. This collection paints an accurate and encompassing picture of the state of the video game industry as far as women’s voices are presented (or excluded), as characters, players, and content producers, but also proposes ways forward for historical video games to achieving their potential to be a more inclusive, diverse, and progressive form of entertainment and education.

The chapters collated here cover an ambitious range of genres (from roguelikes to romance via platformers, strategy games, RPGs, action adventure), platforms (PC and console, as well as mobile), budgets (from AAA to indie), number of players (single player, multiplayer), and methodologies (from close analysis to comparative analysis and qualitative and quantitative studies). Some of the games discussed need no introduction due to their popularity and notoriety: the God of War (Sony Interactive Entertainment, 2005-2022), Assassin’s Creed (Ubisoft, 2007-2020) or Civilization (Firaxis Games, 1991-2016) franchises, whereas others are less discussed which makes their analyses even more compelling: Hades (Supergiant Games, 2018), Choices: Courtesan of Rome (Pixelberry Studios, 2018). Draycott and Cook logically structure the collection into 3 parts, leading us from historical overviews (Part I Commencing Classical Gaming) into discussions of Gods, Heroines and Monsters (Part II) and concluding with considering the representation of mortal women in Part III (Queens and Commoners).

The chapter which opens the volume takes us farthest away in time and space, Japan in the mid-80s, to discuss the first playable female character drawn from antiquity: Athena. Dunstan Lowe offers a comprehensive analysis of SNK’s 1986 game, Athena, as well as its spiritual successors Psycho Soldier (1987) and King of Fighters (1994), to demonstrate how, perhaps surprisingly, girl-centred stories and female protagonists based on Greek mythology proved to be more progressive and popular in Japan then in the following three decades of classical games released in the West.

In the second chapter, Jordy D Orellana Figueroa provides an overview of controversies regarding the representation of female characters in classical video games followed by a quantitative analysis of these representations to argue that historical inaccuracy has plagued the representation of women in classical games from their diminished numbers, voices, and social roles to their physical appearance and clothing. These types of inaccuracies, as pointed out above, are not however as troubling to players as the inclusion of women, particularly in positions of power and agency in games.

The final chapter in Part I continues the discussion of female representation in classical game worlds particularly in relation to its impact on player behaviour within and without game communities. Marcie Gwen Persyn analyses the different types of roles played by female characters in God of War: Ascension, Total War: Rome II, Ryse: Son of Rome, Apotheon and Assassin’s Creed: Origins to argue that the diminished presence, voice and agency of women in these games contributes to the formation of game communities that are hostile to non-male identifying players. Representation – mostly as either “damsels in distress, sex objects or victimised avengers”, Persyn argues, matters because the way women are depicted, sexualised, objectified and fetishized, impacts on how male players respond to them and can promote sexism, misogyny and abuse. Persyn also astutely draws parallels here between classical games and classical academic disciplines, pointing out that the silencing of women in games is not unrelated to the silencing of women in historical scholarship.

Dan Goad opens Part II with a discussion of the monstrous feminine in classical video games to draw parallels between the monstrous representation of female antagonists in games (particularly in relation to their sexuality) and the reinforcing of female sexuality as a danger and threat that needs to be overcome by the male hero.

Amy Norgard in Chapter 5 provides an excellent close reading of Apotheon to argue that deicide in the context of the game can be read as a dismantling of patriarchy. This chapter makes some excellent contributions particularly in discussing how gameplay mechanics contribute to characterization and the gender dynamics. The gameplay mechanics in boss battles against the goddesses Artemis, Aphrodite, Athena and Demeter subvert the more traditional hack and slash combat mechanics encountered in the boss fights with male deity opponents to encourage a different power dynamic between the male hero and the female antagonists. These creative combat mechanics make space for dialogue and allow the players an opportunity to get to know the female opponents as fully fleshed, rounded and developed characters.

In Chapter 6, Sophie Nogan, discusses the representation of women in Rise of the Argonauts, to argue that representation and ideology conflict in the game, despite the fact that RofA makes some positive strides with its inclusion of Atalanta, Medea and Medusa on the Argonaut roster, their representation is problematic. They are transgressive (their femininity contradicts gender stereotypes), objectified, sexualised and although powerful, their power is kept in check by Jason. They serve the male hero and cater to the implied male player gaze therefore reproducing misogynist, patriarchal and heteronormative ideologies.

Kira Jones focuses on Supergiant Games’ most recent title, Hades, to offer an excellent discussion about how the positive representation of Eurydice promotes feminist values like consent, empowerment, and respect. Hades not only offers a rounded and complex portrayal of Eurydice, it also frees her from the tyranny of passivity and silence to which classical myths have consigned her to.

Katherine Beydler discusses the reception and representation of Graeco-Roman Goddesses in SMITE: Battleground of the Gods to argue that the genre specific conventions of a MOBA (multiplayer online battle arena) can offer opportunities for more empowered and nuanced character development. Furthermore, Beydler makes a compelling argument for SMITE’s inclusion in the classroom as part of game-based learning activities centred around the characterization and role of women in classic and modern interpretations of myth.

Chapter 9 focuses on the representation of Aphrodite as a caricature of women’s sexuality in God of War 3. Olivia Ciaccia argues that by portraying Aphrodite as a submissive and oversexualised woman, locked in her bedroom and handcuffed to her bed, initially rejected and eventually used by Kratos’ for information, God of War 3 objectifies the Goddess of love, she is no longer divine, powerful or indeed even human, but completely subjected to Kratos and the player who can play with her as they choose. Ciaccia argues convincingly that the dangers of such an approach are that by identifying with Kratos, players are continually exposed and actively encouraged to use Aphrodite’s, and by extension women’s bodies.

Hannah-Marie Chidwick opens the last section of the volume which is dedicated to representations of mortal women. And what better way to start than by discussing the relationship between women and violence in classical video games to argue against sensationalising and sanctioning violence and brutality against women as entertainment. Following Salvati and Bullinger terminology of the ‘historically real’ – what people perceive as actually having happened in the past (2013), Chidwick discusses at length the double-edged sword of this selective historical accuracy, at once used to keep women out, othered and under-represented and, when included, keeping them ‘in their place’ with needless brutality against women which can easily pass as historical real.

In Chapter 11, Jane Draycott offers a discussion of the portrayals of the Egyptian queen Cleopatra VII in relation to historical accuracy and authenticity in Assassin’s Creed: Origins and Dante’s Inferno. The historically real discussed above returns here as authenticity which, Draycott argues, can help to explain the appeal to the same racial and sexist cliched representations of Cleopatra in ACO – because this is what the audiences expect. Draycott offers an alternative to the explanation that Ubisoft simply capitulated to player expectations and prejudices; she convincingly argues that Cleopatra’s more positive qualities are in fact present, but in the character of Aya. This would have allowed Ubisoft the chance to play into player expectations of Cleopatra whilst at the same time draw from the extensive historical research undertaken to more subtly redeem her.

Andrew Dufton turns our attention to the Punic World to discuss playing as Dido in Civilization VI: Gathering Stormand as Salammbô in Salammbô: Battle for Carthage. He argues that if video games are to distance themselves from orientalist stereotypes and recreate the complexities and nuances of the Punic world they should look beyond Greek and Roman narratives.

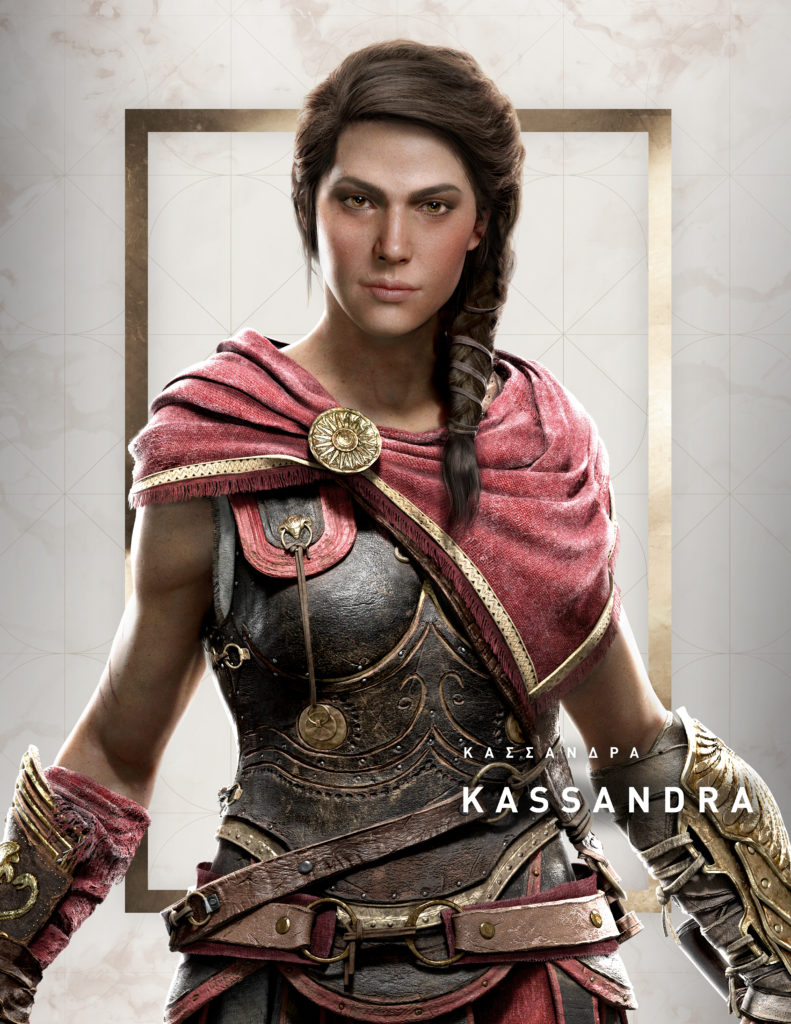

In chapter 13, Richard Cole takes us back to Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey, but this time to discuss the meaning of playing Kassandra. Cole argues against the often-cited statement that deciding to play as either Kassandra or Alexios results in a simple cosmetic difference by offering an in-depth analysis of the game and its paratexts. Choosing to play as Kassandra is a meaningful and powerful action, it has meaning for the player as they experience and see the world as Kassandra, but also because it is in itself an act of defiance: by playing Kassandra they are rewriting history, both ancient (the limited roles, agency and power of women in Ancient Greece) and recent (the limited roles, agency and power of women in historical games).

Roz Tuplin continues the foray into Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey with the clear focus of discussing the representations of sex workers in the game. Tulin offers an insightful and balanced analysis of the hetaerae (sex workers) in Odyssey to argue that Ubisoft have managed to provide a compassionate, human, rounded and progressive representation of sex workers, only to revert to the cliché of transgression: a woman who is in control of her sexuality and manifests political power is a threat and therefore must be (violently) punished. Tuplin’s power of argument is so compelling that I cannot but feel her frustration at watching the game take one step forward only to eventually succumb to the shorthand stereotypes.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the editors have chosen to conclude the volume with a discussion of a mobile title. Mobile games, due to their accessibility and diverse player base, seem to allow more freedom and innovation in terms of representation offering a less hostile environment to women and non-binary players. In the final chapter, Kate Cook offers a refreshing look at mobile games to discuss gender, genre and agency in Choices: A Courtesan of Rome. Cook carefully unpacks the gameplay experience to discuss various aspects relating to the female lived experience which are considered and sensitively represented by the developers: female agency, freedom, and power within the confines of history and patriarchy, as well as female networks as a source of empowerment, support, and agency. This chapter then prompts us to consider whether mobile games are the key and the future for representing more authentic lived experiences of women in the ancient world and beyond?

Women in Classical Video Games is an excellent read not just for the variety of perspectives that it includes, the games that it discusses and the questions that it answers, but also because ultimately it mirrors the purpose of history itself, to document the past so that we may learn from it. By looking back at historical games with a critical eye we can begin to acknowledge and accept where we fell short and understand where, going forward, we can do better.

Book review by Mona Bozdog (Abertay University)

Mona is a Lecturer in Immersive Experience Design at Abertay University where she acts as Programme Co-Lead on the BA (Hons) Game Design and Production. She completed her Applied Research Collaborative Studentship PhD: “Playing with Performance/Performing Play. Creating hybrid experiences at the fringes of video games and performance” at Abertay in 2019. Her Research Project was a collaboration between Abertay University, The Royal Conservatoire of Scotland and The National Theatre of Scotland, funded by RLINCS and The Scottish Funding Council through the Scottish Graduate School for Arts and Humanities. She has published in Games and Culture (SAGE), Journal of Gaming and Virtual Worlds (Intellect), The Scottish Journal of Performance and presented work at numerous national and international conferences and events: DiGRA, CHI, ELO, ResFest, BBC Click Live, Future Play at the Edinburgh Fringe, Games Are For Everyone, Arcadia. She has co-edited The Art of Care, a special issue of the Scottish Journal of Performance. Her research is practice-based and focuses on the convergence of contemporary performance practices and video games, particularly designing hybrid forms of storytelling, performative games, mixed-reality and immersive experiences and games for public spaces and heritage sites. Mona is currently working on a series of projects that investigate the potential of games for capturing, preserving and sharing lived experience and herstory.