So. I’m a curator and a game designer. I work on a lot of different sorts of games: games to play at home, games for museums, games for festivals, games for schools, occasionally even games for computers.

Often, these are games with some sort of connection to history, usually made as half of Matheson Marcault, in collaboration with my colleague Sophie Sampson.

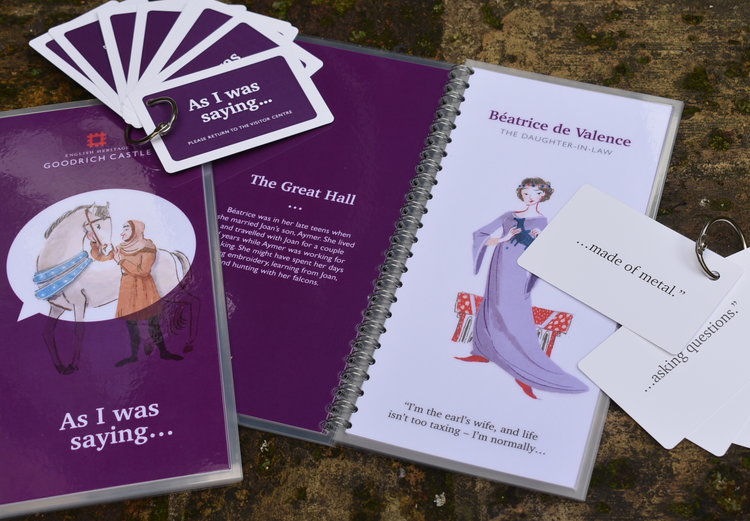

Sometimes these games are directly informed by specific historical moments. So for example As I Was Saying, which we made for Goodrich Castle in Herefordshire, is based around the time that Countess Joan de Valence spent living in the castle in the late 1290s. She wrote a lot of letters, so historians have amazing records of that time: who was there, what they got up to, where things happened. And the game focuses on digging into those details, what we know about the day-to-day life of the people who accompanied the countess, how the castle worked, who was in there and what they did.

In other cases, the connection to history is more oblique: for example, One Easy Step, a temporary installation for the Quad at King’s College. Here, the primary aim of the installation was to get people moving around and responding to and noticing the space in new ways; but the history of the location informed our design. A hundred years previously the Quad had been a school playground, and hundreds of years before that a geometrical garden, and we drew on both of those inspirations while thinking about what might work well. These historical connections aren’t educational in this case — you wouldn’t expect anyone wandering through One Easy Step to think about the historical background unless it’s something they were already aware of. Instead the connections are inspirational: when we’re making work for a specific public space, knowing about the past uses of that space helps to prompt different ideas and approaches. (It also makes it more possible to avoid inappropriate uses of a space).

And then there are in-between games which draw less upon specific historical details, but which still have an educational or education-adjacent purpose; I’m thinking of games like Manifesto, which we made for Furtherfield to run at Frequency Festival in Lincoln. Our brief was to connect to Magna Carta and to themes of democracy, but not necessarily to draw out any specific historical details; so we ended up with a fill-in-the-blanks competitive manifesto game, where players tried to assemble manifestos that they were happy to stand behind while racing against the clock. In some versions of the game, passers-by are then invited to vote on their preferred manifesto.

So in our work there’s this really wide range of ways of engaging with history, everything from using it as a jumping-off point that we expect most players to miss entirely, to focusing on it as a core part of the player’s experience.

I thought in this context it might be interesting to talk a little about my experience as a designer, and the contexts that make it possible for those historically-inspired games to be — well — good.

Not necessarily good as history. That’s another set of issues, with its own solutions: say, clear and informative briefs; early collaboration between designers and historians; time and budget built in for sign-off and revisions; early clarity about what sources and resources are available; ensuring that we as designers understand not just what is known about the historical context but also how it’s known, and what else we might plausibly be able to find out; and a lot of other details that differ from project to project.

But rather: good as a game.

If someone is commissioning or calling for historical games, from my perspective as a designer, here’s what I get excited about seeing in a brief.

Clarity and flexibility about the desired learning outcomes

Not everything is suitable for communicating through a game. A project brief with extremely specific outcomes around particular facts can be really difficult to work with, especially as there’s bound to be constraints around space, time, budget, type of game as well.

At the same time, a brief to just make a game that’s informative or educational in a broad sense, without clarity about what sort of information or education needs to come out of the experience, can make it hard to evaluate game concepts and figure out which ones work best. A brief that’s clear about what a good outcome looks like can help with both initial design and with refining that design through playtests and feedback.

What’s the middle ground between “too specific” and “not specific enough”? Well, I think briefs for educational historical games tend to work well when they provide a subject area, whether that’s narrow or broad; details about the type of learning that needs to come out of the game; and just a whole bunch of information about the period, place, subject area that can then become one of the materials of the game-making process, one of the things the designers are going to be able to dig into and work with. So for example, we’ve had briefs to:

* Make a playground game for primary-age children that communicates… something… about the Battle of Hastings. Players should be made aware that the Battle of Hastings happened, who it was between, how it worked out

* Make a card game for families that draws on existing information about what was going on in Goodrich Castle in 1296-1297, as documented primarily in the letters of Countess Joan de Valance (as mentioned above)

These are radically different prompts in terms of specificity, but in both cases we were able to use the historical sources as materials to dig into: the briefs were about defining an area of interest and the way that players’ understanding should change as a result of the game, rather than either giving specific facts on the one hand, or on the other just generally evincing a desire that the game be educational without defining what that would look like.

Which leads to my second point:

Just a whole bunch of information and a whole heap of sources, and ideally a historian or two to talk to

It’s hard to say in advance what historical moments or details will prompt a game idea, what particular aspects of a past event are suitable for whatever the game design ends up being.

An ideal brief lets the designer look for the stuff that’s fun, that’s interesting, that they can hook a mechanic onto, that people will think is funny. Again, this can be super-specific, or it can be more general — but the important thing is that it’s a resource that can be drawn on in creating the game, that there’s scope to dig around and discover and respond.

If it’s possible to have an expert’s time, a historian who can provide information and answer questions and suggest possible areas of interest and resources, then that’s even better, especially at a few key points: when starting out, to help the designer understand the scope of the subject and find little corners of interest that they might otherwise miss; when getting the game ready to playtest, to ensure that it fits with the history; and during a post-playtest signoff period. Knowing in advance that this sort of engagement will be possible is incredibly useful.

A commissioning process based on approach and track record rather than concept

So, I’ve been arguing that a lot of the best ideas for educational historical games come from really, really digging into the space and the history and finding the moments or approaches that can be used to create and facilitate play.

What this means in practice is that the sort of ideas it’s possible for game designers to have in response to an unpaid open call are often just… not the best ideas. If you ask designers to have an idea for no money in order to win a commission then what you will get are ideas that those designers can have fast: that draw heavily on previous work or their existing knowledge of a period or place or a genuine but relatively superficial engagement with the information that you’ve put in your brief. You might still get something great! But you might not.

If you want to get the best game concepts for a space and theme and period, the designers need time.

The approaches that seem most straightforward to me are to either commission someone based on their general approach and work you’ve seen in the past, so that they have time to engage fully before making their proposals; or if the commission is large enough, to have a paid proposal process where the designers or companies you are considering are able to put at least a couple of days into thinking through the possibilities and coming up with something that is more deeply based in the specific history and details of the call.

I realise I’m not exactly neutral in this. I mean, I’m a game designer, obviously I’m going to say it’s good to give game designers money. But I do genuinely think that you will end up with better games if it’s possible for the designers to dig into the history to have their ideas, rather than come up with something in the day or half-day or hour that they can afford to spend on having an idea on spec.

Consideration of what play means in that specific space

And finally: look, play can be a weird use of a space. People who are playing will behave unpredictably, they will replace the usual rules of behaviour in a space with the rules of the game.

So designers of games for historical sites in particular need to understand what the restrictions are on how weirdly people can behave, what is an acceptable alternate use of the space and what isn’t. Can people run? Can they take photos? Is it okay if they talk louder than everyone else? Is it all right if they stay in one particular place in front of, say, a particular cabinet for half an hour?

If a commission or a call can be up-front about what the restrictions on the use of the space are, and conversely what weird uses would be encouraged, then that’s incredibly useful.

Of course, nobody needs a four hundred page document at the start of a project going through exactly what is allowed where in a building, maximum brightness permitted for lights within four metres of a particular cabinet, any tokens used in the games must be at least 1.5 centimetres on the narrowest side to prevent them falling between gaps in the cobbles, the hundreds of little details and restrictions that often only emerge the first time someone asks hey, can we do this unusual thing?

But people playing a game use the space that they’re in differently, and when commissioners think about what sort of use is okay and what isn’t, then that helps to suggest the types of play that might be possible in the space, and stops designers from getting carried away with things that might be impossible. And in some cases, it gives designers permission to have wilder and stranger ideas than they otherwise might have, and ensures that any limits they put on what is permissible are based on the real restrictions of the space, not their assumptions about what heritage spaces permit; I’ve certainly had moments where I’ve asked “are we allowed to…” and then received a “yes” that I wasn’t expecting.

Holly Gramazio is a game designer, curator and writer. Holly’s research interests are in games that invite people to make something creative while they play, or that get players looking at their environment in new ways (Holly tends to make a lot of site-specific work). Holly founded Now Play This, a festival of experimental game design based at Somerset House in London and running annually as part of the London Games Festival. Her more recent projects include writing the script for videogame Dicey Dungeons (winner of the 2019 Indiecade Grand Jury Award) and putting together New Rules, a collection of essays about play during the pandemic.