Technology trees are everywhere.[1] They’re a really useful game design tool. But they come with a lot of baggage and often don’t align with scholarly or popular views of the past. In particular, this often leads to unusual representations of the ‘Dark Ages’.

The medieval world is typically presented as backwards and superstitious[2] (not to mention violent and dirty),[3]exhibiting substantial technological and intellectual regression from the glories of the classical world.[4] This slide into darkness is often portrayed as spanning the centuries until the illumination of the renaissance or enlightenment reinvigorated humanity’s progress towards the stars.[5]

There are obvious issues with this depiction of the Middle Ages. For starters: it’s hugely Eurocentric, ignoring Golden Ages of learning in Baghdad, Timbuktu, Beijing and elsewhere. It also ignores any cultural, social, or technological change in Europe during the period – including the formalisation of universities – and the concept of the Dark Ages exists primarily to distinguish the ‘modern’ world from the medieval, and emphasise the superiority of contemporary society. Nevertheless, the Dark Ages remain firmly rooted in the popular imagination.

Very often the image of the medieval world as the Dark Ages makes its way into digital games. Games likes Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla (2020) and the Dragon Age (2009-2024), Witcher (2007-2015), and Elder Scrolls (1994-2024) series are littered with ruins of precursor civilizations who were clearly more technologically advanced than the current inhabitants of the game world.[6] These ancient sites house powerful weapons to be looted and powerful adversaries to be overcome.[7] Within these games, much of the population is portrayed as superstitious, uneducated or primitive.

A Forest of Tech Trees

The main exception to these Digital Dark Ages is found in the almost ubiquitous technology trees of the strategy genre.

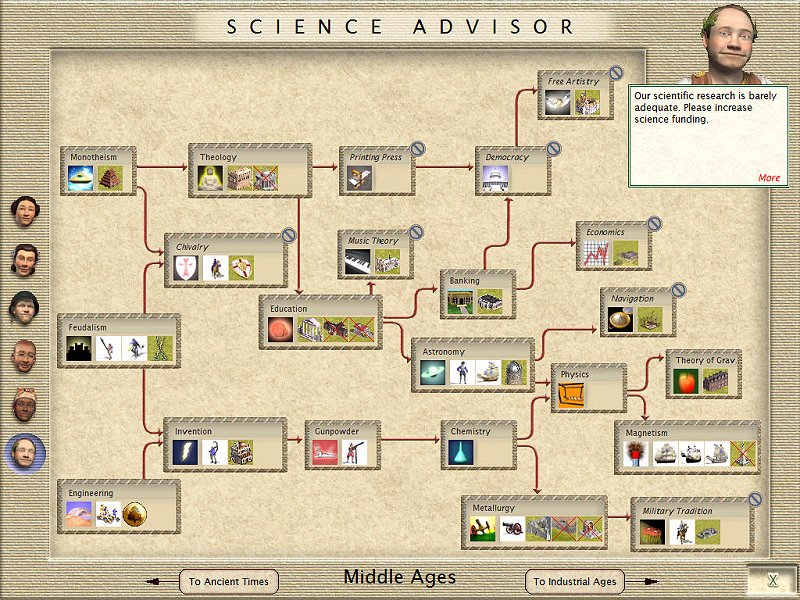

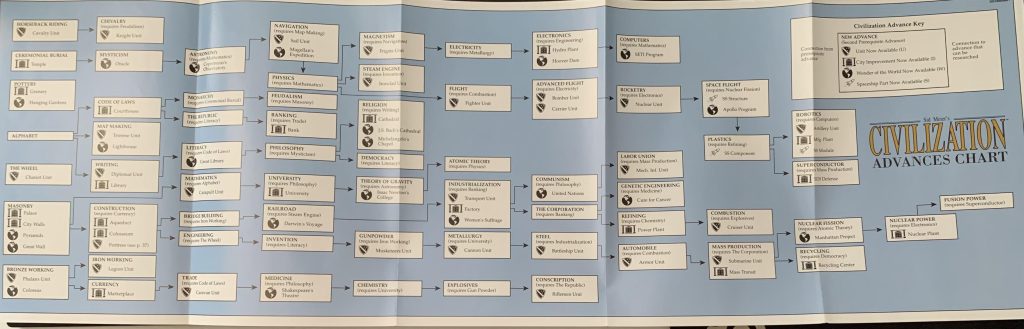

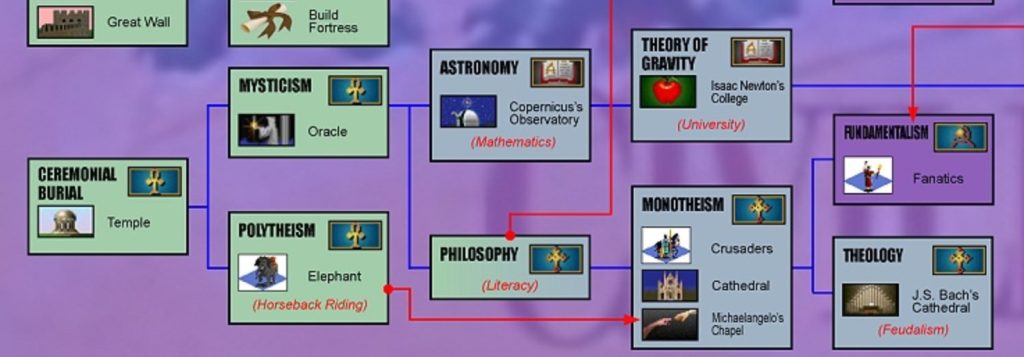

Ever since Civilization and Master of Orion codified many of the conventions around turn based strategy games, the ordering of science and technology into neatly arranged trees of progression has abounded across historical and science fiction settings. These foundational behemoths of the strategy genre quantified research and knowledge as concrete resources (comparable to food and production materials) to be generated by centrally directed scientists, working to uncover a discrete series of technological advances which would allow access to ever more powerful weapons, buildings, and other abilities. These individual technologies ranged from ‘Pottery’ and ‘Ceremonial Burial’ in the ancient world through to ‘Nuclear Fission’ and ‘Space Flight’ in the modern period. Most technologies opened up access to new subjects for research and these scientific discoveries were arranged into a neat tree. Later strategy games have experimented with these trees in various ways – randomising the availability of certain technologies, providing different routes through the tree, or creating parallel systems for social or cultural change – but the core concept remains heavily visible in games from Age of Empires to Stellaris.

It’s fairly easy to see why this model for scientific change has remained so ubiquitous within strategy games. Tech trees provide an easy visualisation of this core concept of the game and facilitate strategising and planning by players. Allowing the player to direct research likewise simplifies a potentially complex issue to facilitate game play, and also grants new strategic options – do you choose to research ‘Gunpowder’ for its military potential, or to focus instead on ‘Banking’ for its capacity to enhance your income? Establishing a tech tree which remains identical in any playthrough ensures that strategies will remain relevant across multiple games. Perhaps most importantly, presenting a series of technologies which provide systematic advantages to the player’s faction allows a tangible feeling of progress throughout the game which is a core conceit for much of the medium – indeed there is a striking similarity between the tech trees of strategy games and the systems of character improvement common to action, adventure and roleplaying games.

Averting the Digital Dark Ages

Of particular interest to me as a medieval historian, tech trees present a ‘March of Progress’ narrative.[8] Every technology is universally superior to those which came before, granting access to more powerful units, lucrative buildings, or other benefits. New technologies likewise seldom have negative consequences to their adoption (earlier versions of Civilization rendered several world wonders and, more occasionally, buildings obsolete after certain technologies were researched, but this came to an end with Civilization V). Furthermore, this march of progress is irreversible. Once a technology has been discovered it may never be lost, so there is no scope for regression into a more ‘primitive’ level of technology.[9]

This motif of constant progress stands in stark contrast with the common depiction of the Middle Ages as the Dark Ages and leads to a very different depiction of the period. The Middle Ages in most strategy games simply forms part of the broader chain of progress as depicted within the tech tree, following on from the ancient world and leading into more modern periods. The model of incremental progress over time is retained through the medieval eras of these games, with each technology of this period representing an improvement on those of the ancient world. Hence in Civilization VI,the medieval technologies ‘Apprenticeship’, ‘Military Engineering’ and ‘Stirrups’ effectively provide better versions of the units and buildings unlocked by the classical technologies ‘Iron Working’, ‘Engineering’, and ‘Horseback Riding’. The Middle Ages in tech trees are not Dark, but are simply a stepping stone between the ancient and modern worlds.

A faint echo of the Dark Ages is retained in many of these games, but this is typically overwritten by the deeper message of inevitable progress. There is a tendency to focus on religious and social ‘technologies’ in the medieval portion of the tech tree as opposed to the more scientific and economic technologies of the modern world. A few games present some medieval ‘technologies’ as dead-ends: in the original Civilization, ‘Chivalry’ led to no new technologies, a characteristic shared by ‘Theology’ in Civilization II. Nevertheless, the medieval technologies represent a degree of progress, providing access to better units, buildings or other abilities. A handful of games attach disadvantages to medieval technologies – most notably in Total War: Attila the string of Roman religious technologies representing the rise of Christianity progressively deny the faction the ability to construct useful and archetypically Roman structures such as aqueducts, forums, and baths. But even here the disadvantages are more than outweighed by the benefits provided by these new technologies.

As a result, the technological Dark Ages don’t generally exist in strategy games. Instead, the Middle Ages form part of a broader model of progress spanning all of human history. This most persistent of tropes is firmly put to bed.

The Trouble with Tech Trees

But while tech trees are very useful from a game development standpoint, they present a few questionable accounts of technological change. Cultural, social, philosophical and religious changes are incorporated into many of these tech trees and are ‘researched’ in the exact same way as more scientific technologies: hence scientists will discover ‘Feudalism’, ‘Ceremonial Burial’ or ‘Democracy’. The presentation of technologies as a series of sequential unlockables likewise throws up a few oddities. In Civilization II for example ‘Horseback Riding’ was an indirect prerequisite to research ‘Monotheism’, ‘Refrigeration’, and ‘Space Flight’, and similar contingencies appear in every iteration of Civilization.[10] Furthermore, the mechanisms around these tech trees often imply that technological research is always centrally directed, always focused on one avenue of research at a time, and that a new technology is immediately adopted across a polity as soon as it is discovered.[11] Moreover, this sequential unlocking of technologies implies that there was only one possible arc for human development – and this arc tends to be Eurocentric and leads to the creation of societies looking very similar to the modern USA.[12] The entire system is built around exploring the world, expanding the empire, exploiting the environment, and exterminating opposition (the 4Xs defined by Alan Emrich),[13] reinforcing a colonialist and imperialist view of the world.

Most fundamentally, the model of constant progress which is inherent to most tech trees comes with a host of problems. The implication is that more recent technologies – and social, cultural, and philosophical ideas – are invariably superior to those that came before, with no consideration of any negative impact.[14] The social upheaval and unrest of the agricultural and industrial revolutions doesn’t get a look in. ‘Monotheism’ is typically mechanically superior to the earlier ‘Polytheism’. With the occasional exception of nuke happy rulers, the mass destruction inherent to the technologies of modern total warfare is obscured. Ultimately, the model builds towards an image of the present or near future as the pinnacle of human achievement.

Chopping Down the Tech Tree?

Altering the core idea of the tech tree is fairly unpalatable to both developers and players – it’s too effective a mechanic to be discarded and it’s an expected part of the genre – but there are still several ways in which its issues can be alleviated. Presenting the consequences of the adoption of new technologies could be an effective path here. Civilizationhas intermittently experimented with climate change as a late game issue, with several games in the series monitoring rising pollution tied to the adoption of new technologies and their associated buildings. The Gathering Storm expansion for Civilization VI presents particularly severe consequences for this climate change, with rising sea levels systematically engulfing coastal regions. The developers of Civilization VII (2025) look to be adapting and expanding this late game crisis to create breaks and ‘Dark Ages’ throughout the timeline of the game – including various ways for the ancient world to collapse into a medieval Dark Age.

Displacing the Dark Ages with this Whiggish historical model is replacing one limited and sometime troubling model with another. Both models can create potent gameplay opportunities, but they are often flat both in their historical representations and in the variety of repeated playthroughs. There’s potential to do more here, and there’s plenty of appetite for this from both developers and players. Tech trees cause plenty of trouble, but they offer a way to avert the Digital Dark Ages and engage with history in a more interesting way.

Robert Houghton is a Lecturer in Early Medieval History at the University of Winchester. His research focuses on Italian political and social networks, and on medievalist computer games. Recent publications include Playing the Crusades, The Middle Ages in Modern Culture, and Teaching the Middle Ages through Modern Games. Rob has worked with The Public Medievalist and with Paradox Interactive, and is currently the lead organiser for The Middle Ages in Modern Games Twitter conference. His book The Middle Ages in Computer Games is out now.

[1] This piece draws on material and discussion published in: Robert Houghton, The Middle Ages in Computer Games: Ludic Approaches to the Medieval and Medievalism, Medievalism 28 (Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2024).

[2] Helen Conrad-O’Briain, “Were Women Able to Read and Write in the Middle Ages?,” in Misconceptions about the Middle Ages, ed. Stephen J. Harris and Bryon Lee Grigsby, Routledge Studies in Medieval Religion and Culture 7 (New York: Routledge, 2008), 236; Peter Dendle, “‘The Age of Faith’: Everyone in the Middle Ages Believed in God,” in Misconceptions about the Middle Ages, ed. Stephen J. Harris and Bryon Lee Grigsby, Routledge Studies in Medieval Religion and Culture 7 (New York: Routledge, 2008), 49; Peter Dendle, “The Middle Ages Were a Superstitious Time,” in Misconceptions about the Middle Ages, ed. Stephen J. Harris and Bryon Lee Grigsby, Routledge Studies in Medieval Religion and Culture 7 (New York: Routledge, 2008), 115; Stephanie Trigg, “Medievalism and Convergence Culture: Researching the Middle Ages for Fiction and Film,” Parergon 25, no. 2 (2008): 111; Elke Koch, “Magic, Media, and Alterity in Catweazle,” European Journal of English Studies 15, no. 2 (2011): 162–63, https://doi.org/10.1080/13825577.2011.566699; Amy S. Kaufman and Paul B. Sturtevant, The Devil’s Historians: How Modern Extremists Abuse the Medieval Past (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2020), 15–18.

[3] Vivian Sobchack, “The Insistent Fringe: Moving Images and Historical Consciousness,” History and Theory 36, no. 4 (1997): 9–10; Bettina Bildhauer, “Medievalism and Cinema,” in The Cambridge Companion to Medievalism, ed. Louise D’Arcens, 1st ed. (Cambridge University Press, 2016), 53, https://doi.org/10.1017/CCO9781316091708.004.

[4] Richard Raiswell, “The Age Before Reason,” in Misconceptions about the Middle Ages, ed. Stephen J. Harris and Bryon Lee Grigsby, Routledge Studies in Medieval Religion and Culture 7 (New York: Routledge, 2008), 124–25.

[5] David Matthews, Medievalism: A Critical History, Medievalism, volume VI (Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2015), 20–21; Andrew B. R. Elliott, Medievalism, Politics and Mass Media: Appropriating the Middle Ages in the Twenty-First Century, Medievalism 10 (Woodbridge, Suffolk: D. S. Brewer, 2017), 55–77 esp. 77.

[6] Patrick Butler, “Ashen, Hollow, Cursed: Fragile Knighthood in the Dark Souls Series and Its Medieval Antecedents,” in Playing the Middle Ages: Pitfalls and Potential in Modern Games, ed. Robert Houghton (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2023), 228–29.

[7] Dom Ford, “Lost Futures: In the Presence of Long-Lost Civilisations in The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild,” in Unpublished, 2018, https://doi.org/10.13140/rg.2.2.32490.57286.

[8] Claudio Fogu, “Digitizing Historical Consciousness,” History and Theory 48, no. 2 (May 2009): 117, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2303.2009.00500.x; Eva Vrtacic, “The Grand Narratives of Video Games: Sid Meier’s Civilization,” Teorija in Praksa 51, no. 1 (2014): 95–97.

[9] Vincenzo Idone Cassone and Mattia Thibault, “The HGR Framework: A Semiotic Approach to the Representation of History in Digital Games,” Gamevironments 5 (2016): 174–75.

[10] Fogu, “Digitizing Historical Consciousness,” 117; Gerald A. Voorhees, “I Play Therefore I Am: Sid Meier’s Civilization, Turn-Based Strategy Games and the Cogito,” Games and Culture 4, no. 3 (July 2009): 265, https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412009339728; Ghys Tuur, “Technology Trees: Freedom and Determinism in Historical Strategy Games,” Game Studies 12, no. 1 (September 2012); Vrtacic, “The Grand Narratives of Video Games,” 97–98; Dom Ford, “‘eXplore, eXpand, eXploit, eXterminate’: Affective Writing of Postcolonial History and Education in Civilization V,” Game Studies 16, no. 2 (2017), http://gamestudies.org/1602/articles/ford; A. Martin Wainwright, Virtual History: How Videogames Portray the Past (Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge, 2019), 46–48.

[11] Ramón Reichert, “Government-Games und Gouverntainment. Das Globalstrategiespiel CIVILIZATION von Sid Meier,” in Strategie Spielen. Medialität, Geschichte und Politik des Strategiespiels, ed. Rolf F. Nohr and Serjoscha Wiemer (LIT, 2008), 191–95, https://mediarep.org/handle/doc/3476; Trevor Owens, “Modding the History of Science: Values at Play in Modder Discussions of Sid Meier’s CIVILIZATION,” Simulation & Gaming 42, no. 4 (August 2011): 485–90, https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878110366277.

[12] Fogu, “Digitizing Historical Consciousness,” 117; Voorhees, “I Play Therefore I Am,” 265; Tuur, “Technology Trees”; Vrtacic, “The Grand Narratives of Video Games,” 97–98; Ford, “‘eXplore, eXpand, eXploit, eXterminate’”; Wainwright, Virtual History, 46–48.

[13] Alan Emrich, “MicroProse’ Strategic Space Opera Is Rated XXXX!,” Computer Gaming World 110 (1993): 92–93.

[14] Alex Whelchel, “Using Civilization Simulation Video Games in the World History Classroom,” World History Connected 4, no. 2 (2007), http://worldhistoryconnected.press.uillinois.edu/4.2/whelchel.html; Reichert, “Government-Games und Gouverntainment,” 199–200; Lutz Schröder, “Research the Spinning Jenny, Gain +8% Wealth by Textile Industries: The Transformation of Historical Technologies into the Virtual World of Empire: Total War,” in Early Modernity and Video Games, ed. Tobias Winnerling and Florian Kerschbaumer (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars, 2014), 83–85; Scott Alan Metzger and Richard J. Paxton, “Gaming History: A Framework for What Video Games Teach About the Past,” Theory & Research in Social Education 44, no. 4 (2016): 554, https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2016.1208596; Nicolas de Zamaróczy, “Are We What We Play? Global Politics in Historical Strategy Computer Games,” International Studies Perspectives 18, no. 2 (2017): 166–67, https://doi.org/10.1093/isp/ekv010.