In video game design, the deliberate reuse and reinterpretation of architectural elements can function as a form of digital spoliation, evoking historical continuity, cultural layering, and the passage of time within virtual worlds. Spoliation refers to the deliberate reuse of architectural elements, sculptures, or other materials from pre-existing structures in new constructions or artistic contexts. This practice, commonly observed in antiquity and the medieval period, extends beyond mere material conservation to encompass complex ideological, political, and aesthetic dimensions. Spoliated materials may have served to assert historical continuity, reinforce claims of legitimacy, or symbolize conquest and transformation. As such, spoliation operates as both a physical and conceptual act, reconfiguring the meaning and function of artifacts within new spatial and cultural frameworks.1

Games such as The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt (CD Projekt Red, 2015) employ this visual strategy to construct immersive environments that suggest long histories of conquest, adaptation, and decay. By incorporating fragmented or repurposed structures—whether in ruined fortifications, reclaimed sacred spaces, or cities built atop the remnants of older civilizations—these games mirror historical practices of spoliation, where materials and motifs from the past were integrated into new constructions. This digital appropriation of architectural elements serves not only as an aesthetic choice but also as a means of environmental storytelling, reinforcing themes of resilience, cultural inheritance, and contested histories. Through these design choices, game worlds gain a sense of historical depth, allowing players to engage with spaces that feel layered with memory and meaning. The presence of architectural remnants—whether seamlessly integrated or left as visible fragments—suggest shifting power dynamics, lost knowledge, and evolving cultural identities, enriching both the visual experience and the narrative complexity of the game world.

Spoliation can be seen across the medieval world. Partly driven by practical considerations, such as the availability of high-quality materials, the act also held ideological and symbolic significance and was sometimes used—as is the case in eleventh and twelfth-century Pisa—to establish a civic identity tied to elements of the past. In the 11th and 12th centuries, Pisa actively cultivated an image of itself as the “New Rome,” drawing upon both material and ideological claims to establish continuity with the legacy of the Roman Empire. This assertion was deeply intertwined with Pisa’s maritime expansion, military successes, and architectural developments, all of which reinforced its status as a dominant power in the western Mediterranean.

This perception was contemporaneously articulated in the Carmen in victoriam pisanorum, an eleventh-century epic poem which recounts the 1087 campaign in which Pisa and Genoa raided the North African city of Mahdia.2 The opening quatrain introduces the campaign as comparable to the Roman conquest of Carthage: Inclitorum Pisanorum scripturus istoriam, / antiquorum Romanorum renovo memoriam: / nam extendit modo Pisa laudem admirabilem, / quam recepit olim Roma vincendo Cartaginem.3 In his annotated translation of the Carmen, Giuseppe Scalia suggests that the invocation of Rome was not only a rhetorical device but also reflective of Pisan attitudes towards the ancient city.4

This identity was established in various ways but perhaps was most visible in the choice of materials utilized in the city’s new construction across the two centuries. In his material and stylistic analyses of the spolia in Pisa, Arnold Esch suggests marble objects and architectural elements were often selected from places around Rome, Paestum, and Pozzuoli, and then shipped back up the Tyrrhenian coast.5 This acquisition of Roman marble objects was likely a facet of the city-wide claim that Pisa was closely linked to ancient Rome, or that it should even been considered as a new Rome and should thus adopt similar aesthetic and material practices. The spoils of the 1087 campaign were used to fund the embellishment and endowment of Pisa’s cathedral, suggesting a vested interest in reusing Roman objects to position the city as a New Rome.6

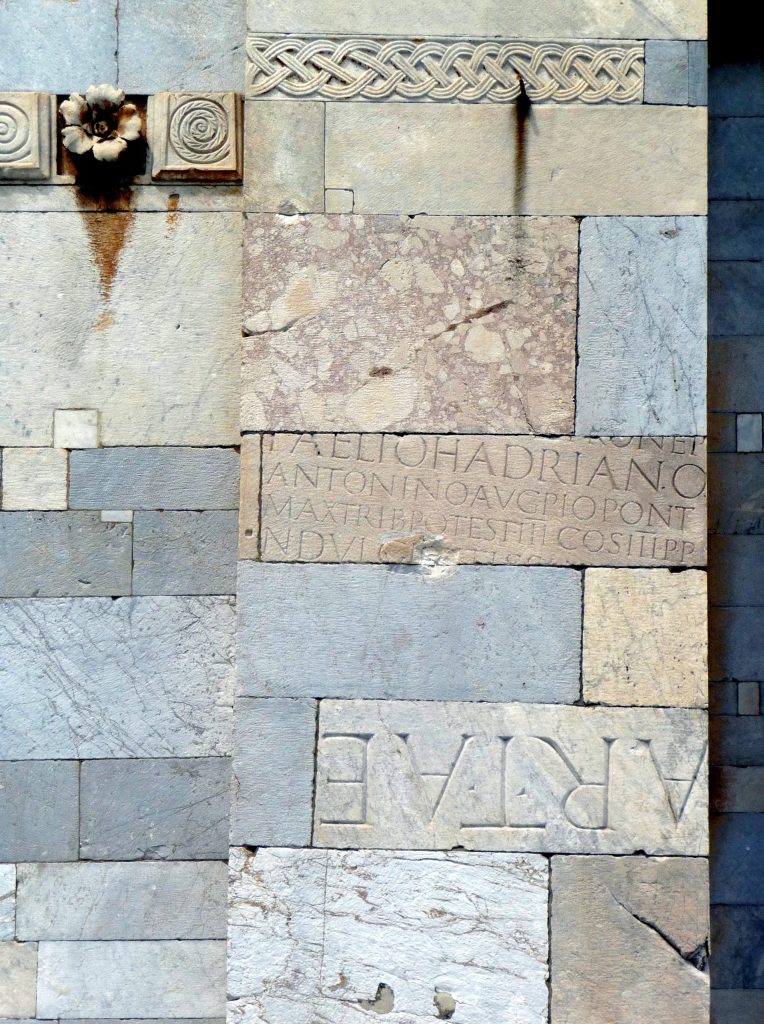

The extensive use of spoliation—ranging from reused columns to an assemblage of marble fragments—could be seen throughout the city, including on the very face of the cathedral.7 The inscriptions which remain visible today (Figures 1-2) could have been removed with minimal effort, so the fact they remain seems to suggest an intent to signal a direct, material connection to Rome.

Video games similarly repurpose architectural elements to evoke deep historical layers within their virtual worlds. In video games, the integration of previous cultural aesthetics in one which often goes unrevealed to the player and can only be deduced by cross-referencing lore and stylistic analyses. Nonetheless, the effect on the player is evident as these subtle design shifts help distinguish old from new, then from now, and help create worlds that have lived histories. While the spoliation practices of medieval cities like Pisa were grounded in tangible political and cultural motivations, the digital worlds of The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt similarly employ architectural reuse to weave complex narratives, bridging past and present through visual storytelling and environmental design.

In The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt, this can be seen in the use and reappropriation of Elven architecture across the Continent. The Elves, or Aen Seidhe, were once a dominant and highly advanced civilization that existed long before the arrival of humans. Following centuries of conflict, displacement, and persecution, their grand cities exist largely in ruins and their surviving communities forced into exile and subjugation. Elven architecture is characterized by its elegant, organic and asymmetric forms and natural integration, with structures featuring flowing lines, delicate carvings, and an emphasis on lightness and openness, as can be seen at the Arthach Palace Ruins (Figure 3). Elven buildings often blend seamlessly with their surroundings, using materials like stone and wood in a way that mirrors natural elements, such as vines or tree motifs in their decorative carvings.

This is most evident in Beauclair Palace (Figure 4), the seat of Toussaint’s rulers, which was designed by Elven architects and retains many elements of Elven stonework, pointed arches, and delicate ornamentation. Rather than reshaping these structures to reflect a new era of imperial control, Toussaint’s rulers maintained them as symbols of refinement and continuity with a more sophisticated past. The nobility viewed elven craftsmanship as a marker of high culture, aligning with Toussaint’s cultivated image as an artistic and idyllic land. This admiration extended to other locations, such as the Elven ruins scattered across Toussaint, which were often left intact or romanticized rather than demolished.

This reverence can be seen within various aspects of Beauclair’s construction, particularly in the elaborate tracery and complex archways. Importantly, as the wall constructed around the city attests, the palace was not let untouched by successive generations. Instead, additions sought to combine elements of the Elven past into new contexts, such as using a partially-ruinated Elven arch as an entrance within the walls (Figure 5).

The in-game description of Beauclair Palace suggests not just a deliberate integration of Elven architecture across the map, but a modern style which deliberately attempts to simulate or recreate the Elven past:

One of the best-preserved artifacts of the elven era, the Beauclair Palace was painstakingly restored and partially rebuilt by the famed Nilfgaardian architect Faramond. Master Faramond, a scholar and expert on nonhuman architecture, is considered the founder of the Neoelven School, of which the Beauclair Palace, home to the rulers of Toussaint, is the most characteristic example.8

The incorporation of both authentic Elven material and simulated Elven design (in the form of Neoelven elements) in the Beauclair Palace under Faramond’s guidance creates a layered architectural narrative that blurs the line between preservation and reconstruction. By using genuine elven stonework alongside Neoelven elements,9 the palace not only pays homage to the lost civilization but also reimagines its aesthetic for a new era, signaling a continuity of cultural prestige while highlighting the human agency in shaping and controlling that legacy. This blending reflects a deliberate effort to both preserve the authentic traces of the past and simultaneously assert human dominance in the present, reinforcing the rulers of Toussaint’s position as both the curators and renovators of the ancient world.

The reuse of Elven architecture in modern Toussaint, particularly in the design of Beauclair Palace, serves as a strategic assertion of cultural continuity and refinement by the ruling class, positioning the duchy as both a guardian and reviver of an ancient, sophisticated legacy. For the player, encountering these recontextualized elven elements fosters a sense of historical depth, subtly linking Toussaint’s present grandeur with the lost civilization of the Elves, thus evoking a layered experience of cultural nostalgia and power while highlighting the juxtaposition between preservation and appropriation in a world marked by its turbulent past. This digital reimagining of spoliation not only enhances environmental storytelling but also reinforces the game’s themes of contested spaces, shifting power, and the reinterpretation of cultural heritage.

In this way, The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt employs spoliation as a means of world-building, using architectural remnants to signal the passage of time, the legacies of past civilizations, and the contested nature of sacred and political authority in its fantasy setting. In both the medieval world and the virtual environments of The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt, spoliation serves as a powerful tool for linking the past with the present, preserving cultural legacies while reshaping them to reflect contemporary power dynamics, thus demonstrating the enduring significance of architectural reuse in storytelling and identity formation.

Blair Apgar is assistant professor of Art History at Elon University. Blair specializes in Northern Italian material culture of the eleventh and twelfth century, virtual reality and 3D modeling, and medievalisms in modern culture. Their recent work on video games has spanned issues of modding and ahistoricism, the constructed and reflected imagined pasts, reflective game design, and historiographical implications of medievalist media. This past fall they also taught a course entitled Playing the Past: The (Art) History of Video Games, which explored video games as historical narratives and cultural artifacts, analyzing their visual language, worldbuilding, and engagement with the past through art historical frameworks. Find them on Bluesky, or @BlairApgar on Steam.

References

- Beat Brenk, “Spolia from Constantine to Charlemagne: Aesthetics versus Ideology,” Dumbarton Oaks Papers41 (1987): 103, https://doi.org/10.2307/1291549; Jill Meredith, “The Arch at Capua: The Strategic Use of Spolia and References to the Antique,” Studies in the History of Art, Symposium Papers XXIV: Intellectual Life at the Court of Frederick II Hohenstaufen (1994), 44 (1994): 108–26; Jaś Elsner, “From the Culture of Spolia to the Cult of Relics: The Arch of Constantine and the Genesis of Late Antique Forms,” Papers of the British School at Rome 68 (2000): 149–94; Dale Kinney, “Roman Architectural Spolia,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 145, no. 2 (2001): 138–61, www.jstor.org/stable/1558268; Richard Brilliant and Dale Kinney, eds., Reuse Value: Spolia and Appropriation in Art and Architecture from Constantine to Sherrie Levine (London New York: Routledge, 2016), https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315606187; Dale Kinney, “The Concept of Spolia,” in A Companion to Medieval Art, ed. Conrad Rudolph, 1st ed. (Wiley, 2019), 331–56, https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119077756.ch14. ↩︎

- Eloise M. Angiola, “Nicola Pisano, Federigo Visconti, and the Classical Style in Pisa,” The Art Bulletin 59, no. 1 (1977): 1–27; H. E. J. Cowdrey, “The Mahdia Campaign of 1087,” The English Historical Review 92, no. 362 (1977): 1–29, www.jstor.org/stable/566299. ↩︎

- Anonymous, Il carme pisano sull’impresa contro i Saraceni del 1087, trans. Giuseppe Scalia (Padua: Liviana, 1971), ll. 1–4. ‘I will write the history of the celebrated Pisans, renewing the memory of Roman antiquity: for I extend to Pisa an admirable praise, which Rome once received by conquering Carthage.’ ↩︎

- Anonymous, 587. ↩︎

- Arnold Esch, “Reimpiego dell’antico nel medioevo: la prospettiva dell’archeologo la prospettiva dello storico” (Spoleto: Centro Italiano di studi sull’alto medioevo, 1999), 78–108; Paul Zanker and Björn Christian Ewald, Living with Myths: The Imagery of Roman Sarcophagi, trans. Julia Slater, First Edition, Oxford Studies in Ancient Culture and Representation (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 3. ↩︎

- Cowdrey, “The Mahdia Campaign of 1087,” 18. ↩︎

- Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, ed. Gaston du C. De Vere, Everyman’s Library (New York: Knopf, 1996), 60–61. ‘1303 A.D…the abovementioned grave was transferred twice, then in the church near the seats, and now here, to this excellent and distinguished space.’ ↩︎

- “Beauclair Palace,” The Official Witcher Wiki, accessed March 10, 2025, https://witcher.fandom.com/wiki/Beauclair_Palace. ↩︎

- Though this term does not get expanded upon within the game, the nomenclature suggests similar revival styles such as ‘neo-Gothic’ and ‘Neoclassical’ which seek to repurpose architectural themes and elements from past architectural movements in modern contexts. ↩︎