While researching my dissertation, I came across a recent book by Andra Ivănescu, entitled Popular Music in the Nostalgia Video Game: The Way It Never Sounded (2019). It’s a very interesting read, particularly the opening chapter, which talks in depth about the BioShock franchise and how the appropriation of genres of music, along with cultural references, effectively evoke a sense of the Roaring Twenties despite the game’s fantastical elements.[1] This led me to consider whether the video games I study do this as effectively when they try to cultivate their own environments.

One song caught my ear, as it is featured heavily in both the games I am presently focused on, which often lean towards alternative history scenarios, as well as games that try their best to cultivate a historically authentic environment for the player to explore. Historically authentic environments are not the same as historically accurate environments; instead they focus on capturing the imagined ‘feeling’ that a particular era or place has in the popular imagination.[2] One way that developers are able to capture this feeling of ‘pastness’ is via the use of songs. The song that appears in the games this article studies is called “The House of the Rising Sun,” the original author of which is uncertain. The song is well-known, and the most successful version was released in 1964 by The Animals, which allowed the song to become a staple of the 1960s as it hit number one in both the USA and the UK.[3] Some have even argued that it was the first folk rock song in history, and ever since then the song has been recorded in various styles over the years.[4] Regardless, the 1964 version of this hit song is one of those pieces that Ivănescu’s work describes. It is a song that undoubtedly evokes a certain era in people’s minds and is a perfect addition to any game that evokes the cultural memory of the 1960s.

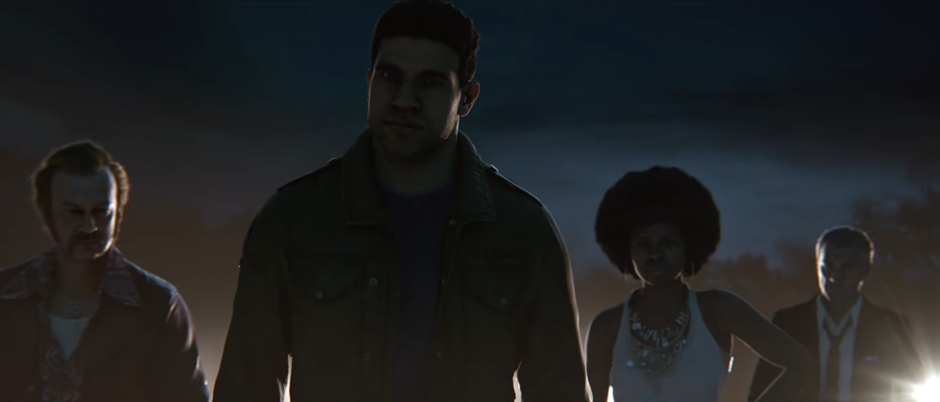

Firstly, let’s look at how a game uses the song to construct a 1960s that appears historically authentic to the player. Mafia III (2016) includes “The House of the Rising Sun” in its soundtrack, alongside a number of other hit songs that similarly evoke the idea and feel of the 1960s, such as “White Room,” released in 1968 by Cream. In Mafia III’s reveal trailer, “The House of the Rising Sun” is used in particular to highlight the main character’s defiance of the existing hierarchical structure that the Mafia has imposed in the fictional city of New Bordeaux, which is heavily inspired by New Orleans.[6] The song itself tells of the way a person’s life has gone wrong in New Orleans, which mirrors the way in which the main character, Lincoln Clay, has had his life effectively turned upside down by Mafia intervention. By having the song play during the trailer’s moment of absolute defiance against this Mafia authority, the game is subtly telling the audience that Lincoln Clay has been personally affected by the Mafia and is not taking the punishment lying down; and it does all of this in a way that helps build a believable, yet fictional region set in 1960s America. The believability, in this case, comes from capturing soundscapes that are true to the period, and specifically in the case of this trailer, aligning the struggles of the main character with 1960s music culture along with utilising elements such as the car radio (and the static that comes with it) to set the historical scene.

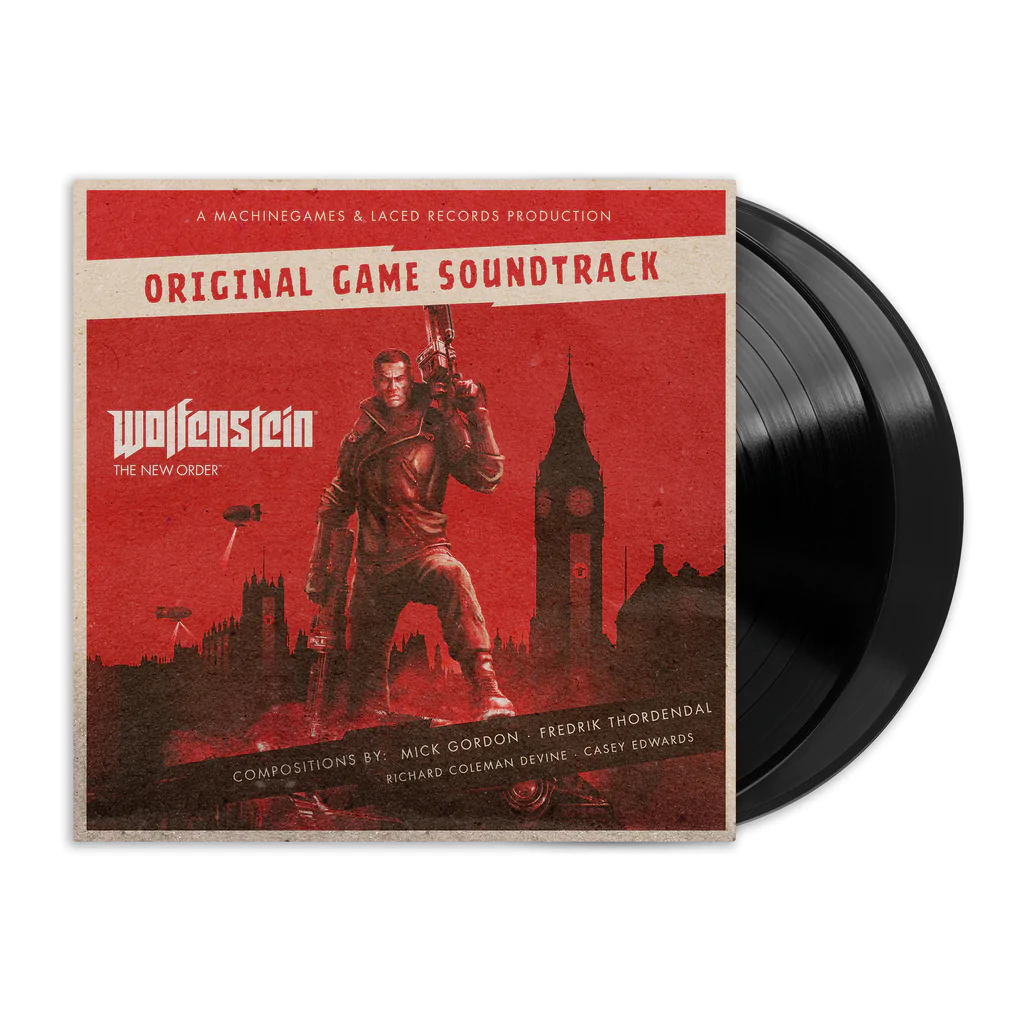

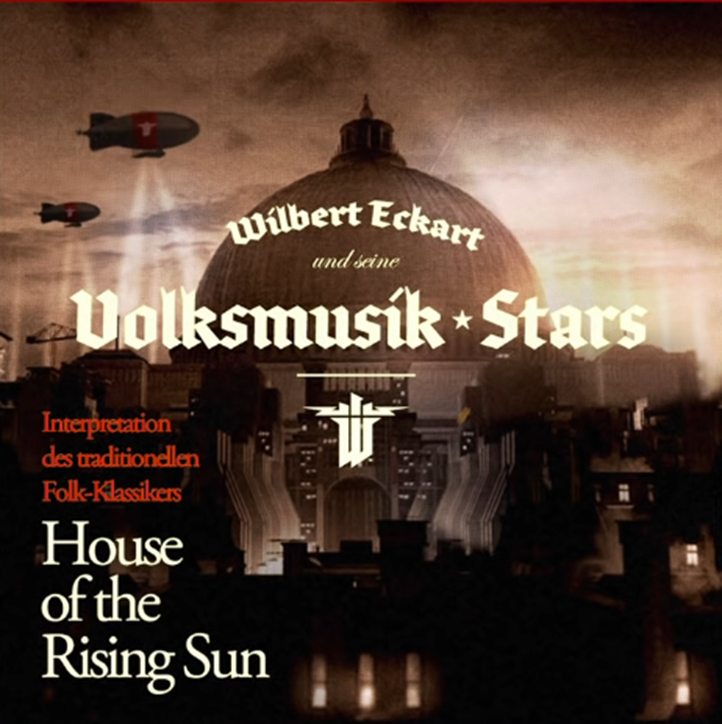

But as I outlined previously, I mainly focus on games that twist history into an alternative version of itself. So, how can a game that spins an alternative history narrative effectively use a song such as “The House of the Rising Sun” to create a world that is alien yet still historically believable? Surely, if it is an alternate history that branches away from our own timeline, the cultural references are less accessible? Not necessarily. Wolfenstein: The New Order (2014) breaks away from our historical timeline immediately upon starting, as the first level is set in 1946 where the Allies are making one last effort to try and gain territory from the ascendant Reich. They fail, and the Nazi forces successfully win the war. Just under 15 years pass, and the rest of the game is set in a 1960s that is drastically different from our own in one key, obvious aspect: the Third Reich now dominates the entirety of the world and is in the process of colonising the other planets of the solar system. Yet despite this, “The House of the Rising Sun” remains an iconic song that is used effectively to help make this world believable. Instead of it being folk rock, it is now played with Volksmusik instruments, and the lyrics are in German. Not only this, but the trailer for Wolfenstein uses the song in a significantly different way than Mafia III. Instead of it symbolising a resistance to authority, it is now appropriated by the authority. Instead of it highlighting the victory that Lincoln Clay has over the Mafia, it is used as a background to Paris being crushed. This sets both the tone of the game as well as the nature of what the player will face. Rather than taking revenge, the player must resist a great authority that looms over them, threatening to transform reality around them in the process. By using this song, Wolfenstein’s developers have effectively indicated the period of time in which the game is set, as with Mafia III, but at the same time highlighted the status quo of this Nazi-dominated alternative world. This, then, is an attempt to reflect the real world as accurately as possible, while still transcending the boundaries of our timeline to tell a satirical story about what might have been.[9] While some might argue that alt-history games do not need to reflect the world accurately, by dipping into the cultural tropes and icons of the time Wolfenstein is able to create a world which feels more immersive, as it is able to be more easily related to by players. Overall, it helps create an environment that feels logical and true, or in other terms, authentic.

Both games, then, use “The House of the Rising Sun” for historical effect, but in remarkably different ways. Mafia III uses it to enhance an allegorical city, to make it seem like a place that one could realistically find in the American south. Wolfenstein uses it to create an unnerving and disturbing alternative 1960s, which feels simultaneously both familiar and terribly wrong. “The House of the Rising Sun,” then, is a marvellous example of popular history that is utilised effectively in historical games to cultivate an environment that feels authentic to the players that choose to engage with it.

Daniel John is a Master’s student at Cardiff University. His current research interests include 20th century ideologies, religion, and historical video games. He is writing his MA dissertation on alternative histories in video games and their relationship to popular nostalgia, focussing on the Fallout and Wolfenstein games.

Bibliography

Primary Sources:

- Mafia III – Worldwide Reveal Trailer | PS4, PlayStation YouTube Channel: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j6dgC5RMXRs (Accessed on 18/03/2022)

- ‘Official Singles Chart Top 50, 09 July 1964 – 15 July 1964’, Official Charts Company: https://www.officialcharts.com/charts/singles-chart/19640709/7501/ (Accessed on 25/04/2022)

- ‘The Hot 100 – Week of September 5, 1964’, Billboard: https://www.billboard.com/charts/hot-100/1964-09-05/ (Accessed on 25/04/2022)

- Wolfenstein – ‘House of the Rising Sun’ Launch Trailer (PEGI), Bethesda Softworks UK YouTube Channel: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OHn6jbK7RE4 (Accessed on 18/03/2022)

Secondary Sources:

- Ivănescu, Andra, Popular Music in the Nostalgia Video Game: The Way It Never Sounded (2019)

- McLean, Ralph, ‘Stories Behind the Song: ‘House of the Rising Sun’, BBC (08/09/11), https://web.archive.org/web/20110908152455/http://www.bbc.co.uk/northernireland/music/story_behind/houseofrisingsun.shtml (Accessed on 18/04/2022)

- Schulzke, Marcus, ‘The Critical Power of Virtual Dystopias’, Games and Culture, 9:5 (2014), pp. 315-34.

- Schwarz, Angela, ‘History in Video Games and the Craze for the Authentic’, in Lorber, Martin and Zimmerman, Felix (eds.), History in Games: Contingencies of an Authentic Past (2020), pp. 117-136.

[1] For further references to the power that certain music has, see Andra Ivănescu, Popular Music in the Nostalgia Video Game: The Way It Never Sounded (2019), pp. 3-4

[2] Angela Schwarz, ‘History in Video Games and the Craze for the Authentic’, in Martin Lorber and Felix Zimmerman (eds.), History in Games: Contingencies of an Authentic Past (2020), p. 119.

[3] “The House of the Rising Sun” hit number one in the USA on the week of September 5, 1964, as shown in Billboard’s ‘The Hot 100’ archive: https://www.billboard.com/charts/hot-100/1964-09-05/ (Accessed on 25/04/2022), while in the UK it hit number one a few months prior, on the week of July 9, 1964, as shown on the Official Charts Company archive: https://www.officialcharts.com/charts/singles-chart/19640709/7501/ (Accessed on 25/04/2022)

[4] Ralph McLean, ‘Stories Behind the Song: ‘House of the Rising Sun’, BBC (08/09/11), https://web.archive.org/web/20110908152455/http://www.bbc.co.uk/northernireland/music/story_behind/houseofrisingsun.shtml (Accessed on 18/04/2022)

[5] Mafia III – Worldwide Reveal Trailer | PS4, PlayStation YouTube Channel: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j6dgC5RMXRs (Accessed on 18/03/2022), at 2:53.

[6] Mafia III – Worldwide Reveal Trailer. The pivotal scene where “The House of the Rising Sun” plays can be found at exactly 3:00 in the video, where a mobster is fed to crocodiles.

[7] Wolfenstein – ‘House of the Rising Sun’ Launch Trailer (PEGI), Bethesda Softworks UK YouTube Channel: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OHn6jbK7RE4 (Accessed on 18/03/2022). This scene is the chilling opening sequence of the trailer, in which the alternate timeline is firmly established.

[8] Wolfenstein – ‘House of the Rising Sun’ Launch Trailer (PEGI). This album cover is shown at the end of the trailer and can also be found in the game as a collectable.

[9] Marcus Schulzke, ‘The Critical Power of Virtual Dystopias’, Games and Culture, 9:5 (2014), pp. 515.