“The potential of videogames for museums is limitless.”

Museum Lab, 2022.

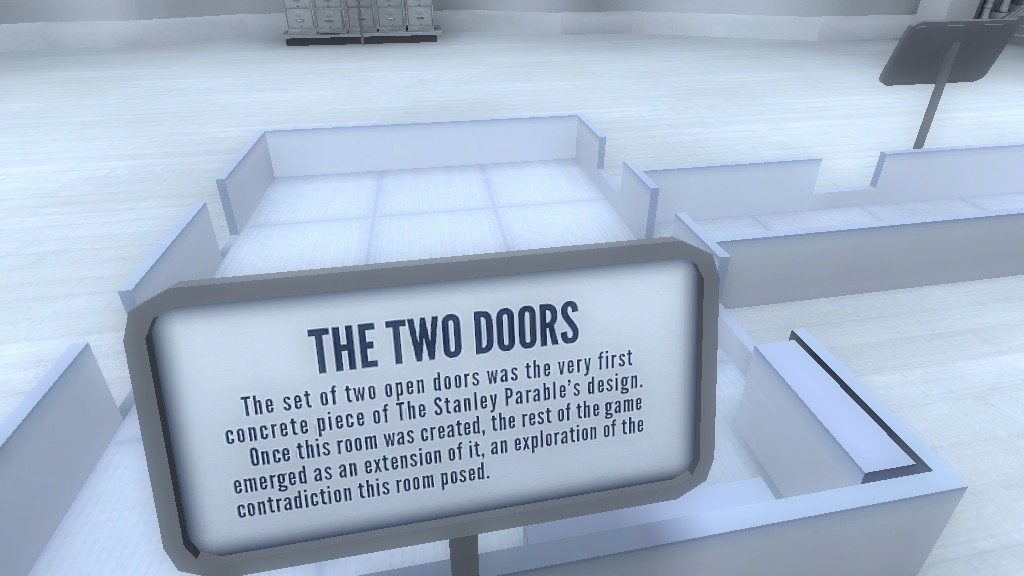

In 2014 I was playing Galactic Café’s The Stanley Parable (2013) – a story-based game with a branching narrative providing commentary on player choice, decision making and game design – when I encountered the game’s ‘Museum Ending’. In this ending, the player is invited to explore a digital museum detailing the development of the very game they are playing, a metaphysical experience which prompted me to think more about the wider relationship between museums, heritage and video games, and the implications of this relationship.

Exploration of the possibilities at the intersection of these sectors is not new by any means. From 2002’s Game On exhibition at the Barbican Centre in London, which delved into the history and culture of computer games, to the establishment of the National Videogame Museum in Sheffield in 2018, both museums and video game developers have used and adapted each other’s mediums to innovate and improve the experience of their audiences. For example, in 2011 the Wellcome Collection developed the trading game High Tea, in collaboration with Preloaded, to accompany an exhibition on the history of mind-altering drugs. Based on the Opium Wars, the game proved popular and provoked discussion between players on the history and ethics of the opium trade. Meanwhile, Ubisoft drew on exhibition design principles to develop a series of ‘Discovery Tour’ experiences for recent releases in the Assassin’s Creed series, linking their recreation of different periods of history back to the artefacts that evidenced and inspired them by including museum objects as part of their discovery tours.

As technology continues to advance, and in many ways become more accessible to a wider range of both players and designers, so does this relationship between museums and video games. Prompted by the development of new projects and a growing field of academic research, this intersection has become ever more complex as museum professionals and game makers seek to better understand each other, and as museums face and overcome limitations (whether in terms of knowledge, capacity, or finance) which have prevented the use of game technologies more widely in the sector. The examples of projects detailed here provide just some examples of the diverse ways in which museums have used video games and game technologies to reach, engage, and cocreate with their audiences. Finally, my own research reveals the surprising similarities between the mediums, and considers how museums could potentially take the use of video games further in the future.

1. Enhancing Education – Great Fire 1666

Education is a common goal of museum engagement with video games, taking advantage of the immersive nature of the medium and the ability of video games to teach through play. Released to coincide with the 350th anniversary of the Great Fire of London, the Museum of London’s Great Fire 1666 campaign involved commissioning the creation of three Minecraft maps which are free to download. Each map provides context on different parts of the historic event, from the pre-fire events to how the fire spread and was tackled and its aftermath. The use of Minecraft and its ability to create 3D representations allowed players to better visualise and understand the layout and structure of 1600s London and how this impacted the spread of the fire. Players are not passive observers in these maps; they are invited through a series of challenges to meet key figures such as Samuel Pepys, whose diary provides a key primary source on the events of the period, to join the effort to fight the fire, and to take part in the rebuilding of the city. Downloaded over 30,000 times, the museum was able to successfully tap into a considerable audience of Minecraft players of all ages.

2. Outreach – Father and Son

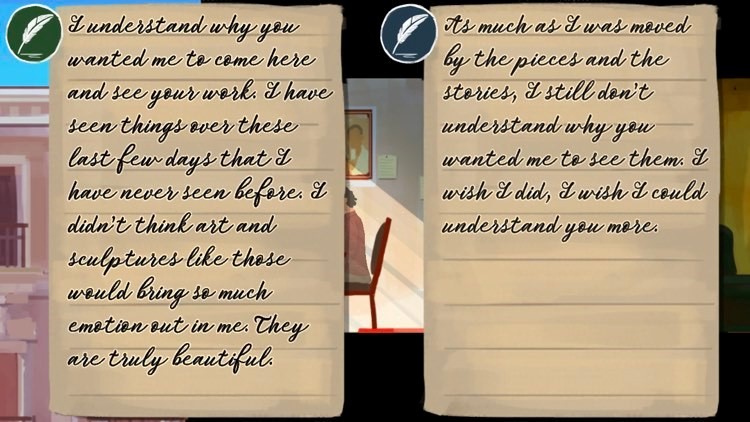

Another common aim of museum games is to reach new audiences – and the audience for video games is substantial. Developed by digital creative studio Tuomuseo for the National Archaeological Museum in Naples, Father and Son is a mobile game which invites players to explore the museum collection through the story of a son trying to understand the work of his father. The game includes a virtual version of parts of the museum and reveals the stories behind those objects by transporting players through time from the last hours of Pompeii to daily life in Ancient Egypt. Interestingly, the game also invites, through a series of narrative choices at the end of the game, reflection upon the experience and how it has impacted the player’s perception of the museum’s collection. Not only does Father and Sontake parts of the collection out to players, it also invites them in by posting QR codes in the museum which can unlock new areas, turning digital players into physical visitors. Within a year of launch, Father and Son had achieved 2 million downloads and over 18,000 players had visited the museum.

3. Embodying a Message – British Library Simulator

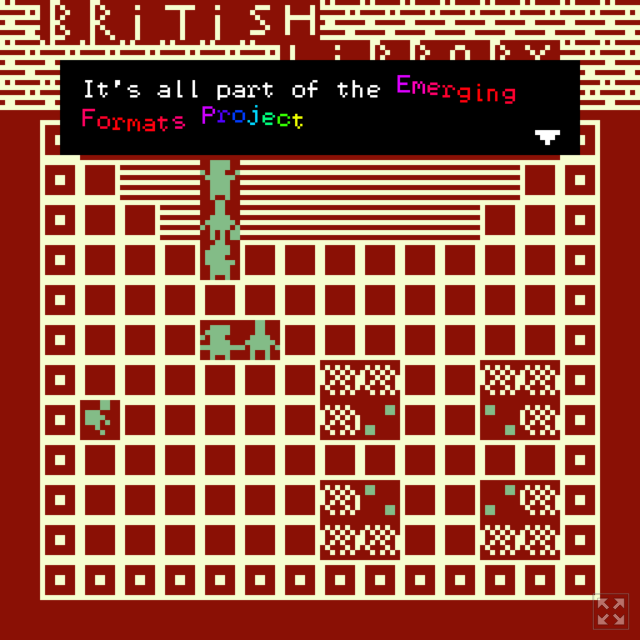

Video games have for some time formed a part of museum collections, but the British Library Simulator took this a step further. A short and relaxing experience produced during the 2020 Covid-19 lockdown, the British Library Simulator provides players with a chance to visit a pixelated version of the British Library and explains library etiquette, the history of the building, and ways that players could access the library’s physical and digital collections from home. The British Library Simulator was created in-house using Bitsy, a free, beginner-friendly game design program, a trend that became increasingly common during the Covid-19 pandemic as the cultural sector shifted its focus to digital engagement. The game also both embodied and formed a part of the library’s Emerging Formats Project, which aims to capture and preserve digital publications such as eBooks, apps, and interactive narratives such as the British Library Simulator, as referenced in the game itself.

4. Prompting Social Action – Utah Climate Challenge

The Natural History Museum of Utah is one of an increasing number of museums engaging with contemporary conversations, topics, and issues. With the museum’s focus on nature, the museum wanted to prompt consideration of climate change, biodiversity, and sustainability, and explored options that might encourage visitors to take action. The result was Utah Climate Challenge, a video game which presented a complex climate system in a way players could understand, but also aimed to meaningfully impact the behaviour of those players within and beyond the museum space. Tasked with building a city of the future, Utah Climate Challenge is a multiplayer game where players must work together to make decisions around different policies, and anticipate the impact of those policies on a changing climate. With over 15,000 players, many of whom played multiple rounds (resulting in a very high dwell time for a museum interactive) the idea, game developer Preloaded states on their website, was for players to realise that, just as in real life, that they must work together to save the future of Utah.

5. Teaching Skills – Virtual Reality Blacksmith

The growing need to teach and pass on heritage crafts to future generations was recognised by Chain Bridge Forge in Spalding, who wanted to find a way to engage young people with blacksmithing to help preserve the skill. However, teaching in the traditional manner was costly in terms of materials and equipment and carried risks from having children and teenagers work with hot metal. The forge turned to digital technology and, in collaboration with the University of Lincoln, developed a virtual reality blacksmith’s forge which enabled schoolchildren to learn how different blacksmithing tasks were undertaken in a virtual environment. Particularly intriguing about this project was the use not only of VR and motion capture tracking which enabled the skill to be recreated as accurately as possible, but of 3D printing which converted digital objects created by players into physical objects that could be taken away as keepsakes. The VR blacksmith project has since become part of a wider innovation lab at the forge. The hope was that VR blacksmiths might go on to take up the trade for real.

6. Interpretation – Hard Craft

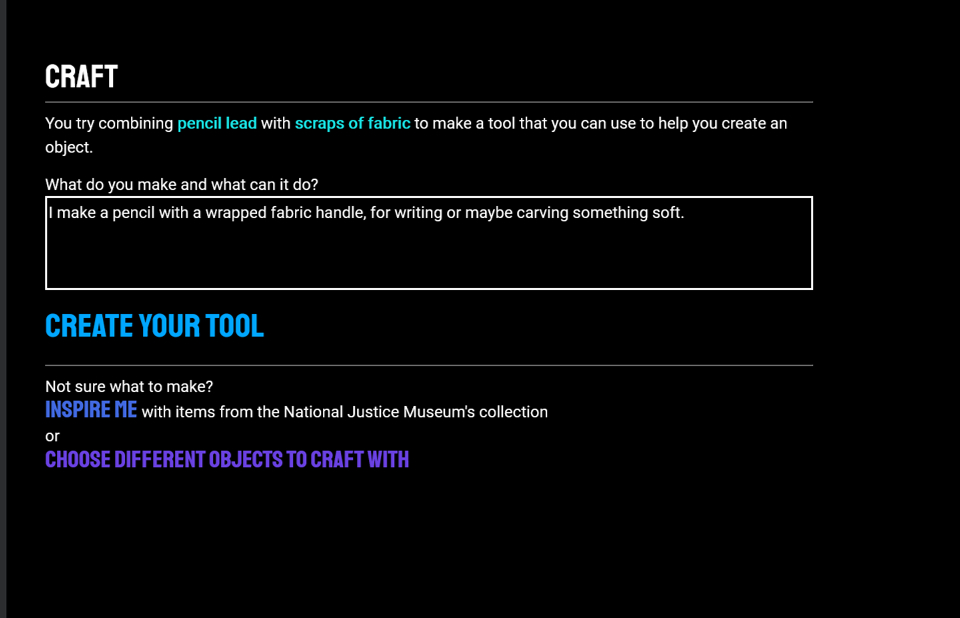

Whilst museum and heritage sites have been testing new uses for games and game technology, academic research at the intersection of museums and video games has been described as “fragmentary” (Camps-Ortueta et al. 2021:196). As such, my PhD research project aimed to take a step back from analysing individual game projects to look at the bigger picture of the convergence between museums and video games as both fields of academic study and industries. What I found was that there are considerable similarities between contemporary museum interpretation practice and video game design principles. Focusing on museum approaches to narrative, emotion and affect, and critical thinking, my research suggested that video games as a medium were capable of realising or even innovating upon interpretation methods museums had been experimenting with to prompt deeper visitor engagement. To explore this further, an outcome of this research was Hard Craft, a Twine game created in collaboration with the National Justice Museum in response to their ‘Ingenuity’ exhibition of objects and art created by people living in person, and which was designed to employ mechanics of video game design to enhance interpretation. Taking a journey of limitation and creativity within a prison-like environment, Hard Craft asks players to collect materials, craft tools and create their own objects, inspired by the collection and the stories they have encountered. In doing so Hard Craft and my research investigates what it might mean for museum games to be designed with interpretation at their core.

Museums are often keen to explore the possibilities of new technologies, and video games have become an increasing part of this. The examples here have evidenced how video games have enabled museums to reach new audiences, teach skills, encourage social action, and engage players with collections and stories. As museum professionals come to better understand the medium its uses diversify, yet academic studies and my own research suggest that there is more that museums can learn from video games which would help the sector unlock the full potential of the medium and use it most effectively within museum projects.

References

Camps-Ortueta, I., Deltell-Escolar, L. and Blasco-López, M., 2021. New technology in museums: AR and VR video games are coming. Communication & Society, 34 (2), pp. 193-210.

Museum Lab., 2022. When Museums Meet Videogames Handbook. Villa Albertine. https://villa-albertine.org/va/news/museum-lab-handbook-when-museums-meet-videogames/

Dr Amy Hondsmerk is a heritage professional based in the East Midlands. Since discovering the field of game studies she has completed a PhD exploring the potential of video games as museum interpretation at Nottingham Trent University and has published and spoken on topics including interactions between museums and video games during the Covid-19 pandemic. As part of this journey she dabbled in game development, undertaking a collaborative placement with the National Justice Museum designing a Twine game in response to the ‘Ingenuity’ exhibition. Alongside her research, Amy taught at NTU on museum engagement contemporary issues such as social justice, digital technologies, and diversity and accessibility. She currently works for Historic England, building on her experience working with a variety of different museums and heritage sites from roles with Culture Syndicates CIC and Mansfield Museum.