The topic of postcolonialism in Asia is directly linked to the aftermath of World War II, when many regions sought independence, like Indonesia. Nationalism in Indonesia developed from the 1910s to the 1940s, as people started to think of a future Indonesia as a single nation free from the Dutch, but these movements were suppressed by the colonial government.

In World War II, Japan occupied Southeast Asia from 1942, and in Indonesia, they promised independence to nationalist leaders to secure Indonesian support for the war in 1945. They provided a conference to discuss the concept of an independent Indonesia starting from ideology. As the war ended, there was considerable fear that the status of Indonesia would revert to the pre-war colonial structure. As a result, the Indonesian nationalist movement represented by Sukarno and Mohammad Hatta proclaimed the independence of Indonesia on 17 August 1945. News about this proclamation spread very rapidly, not only in Java but across many islands in Indonesia. This is where the story of our game, Surabaya Inferno, starts.

Surabaya Inferno is a real-time strategy game focused on the important events in Surabaya from September to November 1945. The game is divided into 3 main scenarios: Consolidation, Fighting Cock, and Inferno.

Consolidation is the opening scenario, where the Surabaya people or Arek-arek Suroboyo must acquire Japanese weapons before the Allies arrive, either through negotiation or by attacking the Japanese armoury. Arek-arek Suroboyo mostly refers to Surabaya youth, since most of the armed Indonesians in Surabaya were youths. This event starts in late September, with the Yamato hotel incident of 20 September 1945, where Arek-arek Suroboyo tore down part of the blue colour from the Dutch flag, which made it the Indonesian flag.

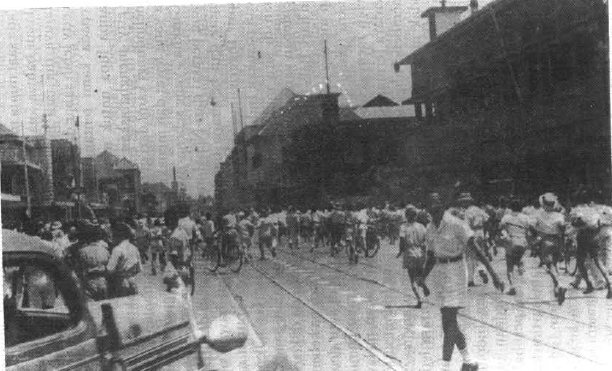

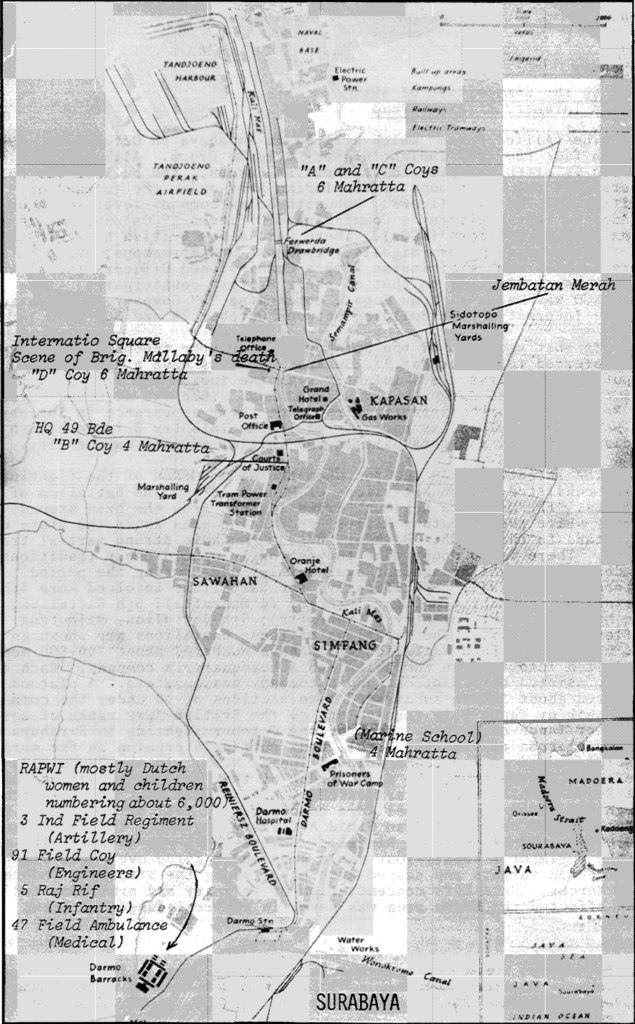

The Fighting Cock scenario relates to the fighting between Indonesian troops and militia – Arek-arek Suroboyo – and the British-led 49th Infantry Brigade on 28-30 October 1945. The main cause of this event was a demand from the Allied commander urging all Indonesians to surrender their weapons on 27 October, which contradicted a previous agreement made with the commander of the 49th Infantry Brigade and further angered the Arek-arek Suroboyo. Allied Forces Netherlands East Indies (AFNEI) troops had landed in several places in Sumatra and Java. On 25 October, the 49th Infantry Brigade arrived in Surabaya to find the city under the control of armed Indonesian nationalists. The Arek-arek Suroboyo, which had amassed considerable weapons and tanks, decided to attack on the evening 28 October 1945. Despite rising tensions, the 49th Infantry Brigade was not fully prepared and had not anticipated the attack. Significant casualties were inflicted upon British and Indian troops, as well as Dutch internees.

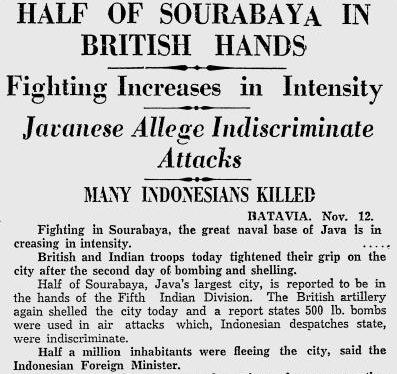

Inferno is the main scenario of Surabaya Inferno and focuses on the Battle of Surabaya, starting on 10 November 1945 when the British 5th Indian Division prepared to attack Surabaya from land, sea, and air unless Indonesian troops and militia surrendered by 6 AM. This demand was in direct response to the killing of Brigadier A.W.S. Mallaby by Indonesian miltia at Jembatan Merah (Red Bridge) on 30 October. Rather than choosing to surrender, Arek-arek Suroboyo chose to fight and defend the city with the spirit of “freedom or death”.

The battle continued for almost 20 days. Although the Indonesian nationalists lost the city and were forced to leave, what happened in Surabaya inspired many more Indonesians in fighting for independence and became a symbol of unity against British and Indian troops.

Research about Revolution in Surabaya

Research is an important aspect of making historical games. Sengkala Dev wanted to make the game as accurate to what happened as possible and translate that into a strategy game.

There are many sources for Surabaya 1945, starting with memoirs written by Sutomo (Bung Tomo, the leader of the Republic of Indonesia Rebel Organization who inspired people by his speech), Student Soldiers: A Memoir of the Battle that Sparked Indonesia’s National Revolution by Hario Kecik, Seratus Hari di Surabaia yang menggemparkan Indonesia or The Hundred Days in Surabaya Which Shook Indonesia by Ruslan Abdulgani, and Mohammad Jasin. These provide the Indonesian perspective. Memoirs written by Sir Philip Christison, and archival reports on Surabaya, form British military viewpoints. From the Indian perspective, there are memoirs written by P.R.S. Mani. Other perspectives come from Ktut Tantri or Muriel Stuart Walker, a Scottish-American supporting Indonesia by addressing English language on Sutomo’s radio and writing her experience in her novel. There are many good books about the Battle of Surabaya, such as Francis Palmos’ Surabaya 1945: Sacred Territory -The First Days of the Indonesian Republic, and Richard McMillan’s British Occupation in Java 1945-1946.

Sengkala Dev developed Surabaya Inferno to be accurate and represent historical events. Accessing some source material was challenging as some books are rare and required library access which was limited due to Covid-19. Where possible we used historical websites to get information about Surabaya. Imperial War Museum video footage of Surabaya provided images of the Battle of Surabaya in addition to the National Archive of the Republic of Indonesia.

We supported these with newspaper archives. There are many newspaper reports on what happened in Surabaya from local newspapers (Indonesia) to foreign newspapers. Local newspapers were difficult to access as the National Library had very strict access requirements due to the Covid-19 outbreak. Online newspaper archives were useful but often limited due to subscription requirements.

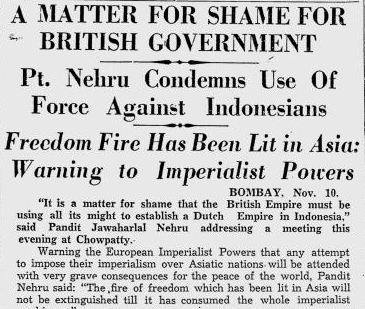

The British Newspaper Archive had good information but was often limited due to the subscription model. In the Google News Archive, we found the Indian Express and this provided interesting information from Nehru’s statement about the struggle of peoples in the Battle of Surabaya, student demonstrations, and more. That the fighting between Indonesian and the Allied forces was headline news in newspapers across the world for several days after the conflict started was of interest.

Unlike British newspapers, the Indian Express gathered other sources and did not depend on the statements from the Allies, which attempted to discredit Indonesia’s struggle and present the fighting as the work of radicals under Japanese control. Instead, official Indonesian government statements and broadcast news, like Sutomo’s radio, were used as sources of knowledge for their articles. They mentioned foreign newspapers such as Pravda voicing Russian concern for the revolution in Indonesia and Indochina. Other articles commented on the Chinese fighting on the Indonesian side against the Allies, referencing military and medical support offered by the Chinese in Indonesia, something very rarely known nowadays due to the strong prejudice against Indonesian-Chinese. This prejudice is rooted in Dutch colonialism of the late 18th century: after Javanese and Chinese fought together against them in the 1740s, the Dutch implemented a number of segregation laws which continued into Suharto’s government, and which required Indonesia-Chinese loyalty to Indonesia, not China. For this reason, the history of shared struggle by the Indonesians and Chinese has mostly been covered up, and it was rarely mentioned until the reformation era in 1998-1999, which gave much greater freedom to Indonesian-Chinese.

We also watched video footage documenting British and Indian troops fighting in Surabaya from the Imperial War Museum website, which was better quality than the Indonesian video. This gave us an image of what Surabaya was like at that time.

According to “Participation Artist in Independence Struggle at East Java Province: Study Case Surabaya City in 1945-1949” from the Republic of Indonesia Department of Education and Culture, many artists and musicians joined the Battle of Surabaya and made many works based on these events. During the battle, many street artists drew on buildings and put up posters to encourage people to fight, and to tell British and Indians not to fight for Dutch purposes. A poem about a battle in a viaduct was written by Luthfi Rahman, recalling his experience in a railway viaduct when the enemy fired a mortar and killed many young people. Moh. Sochieb used his experience in painting to capture what happened in Surabaya, creating many epic paintings.

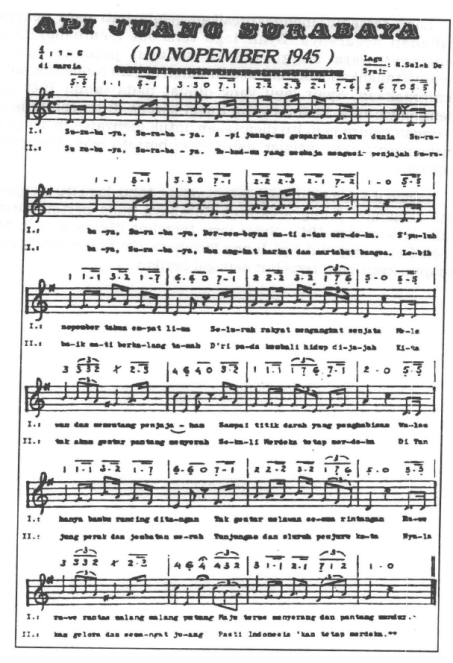

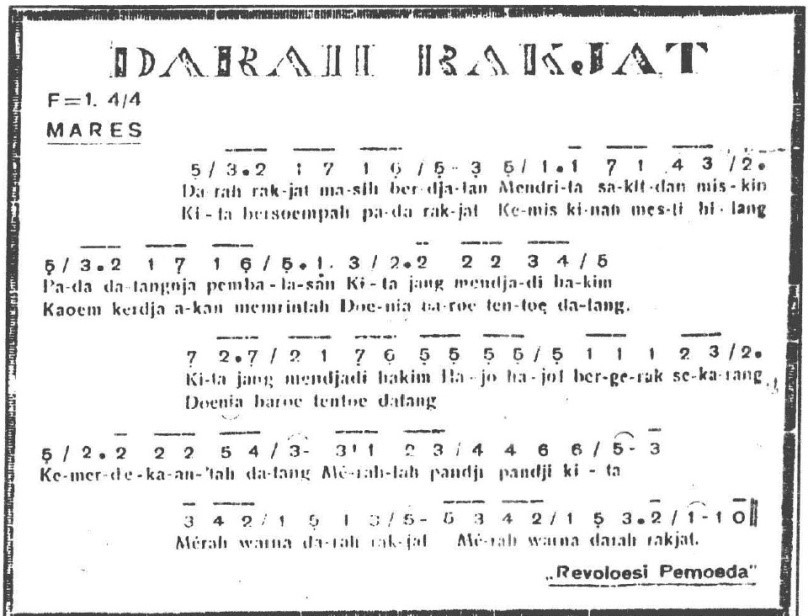

The battle also inspired songs, such as Api Juang Surabaya (Flame of Surabaya’s Struggle) by M. Saleh Dewo, some of which were used when the battle was raging, such as Darah Rakjat (The Blood of the People). These songs inspired the music in Surabaya Inferno and were translated well by Raden Agung, an experienced composer.

Many of the sources we used focused on what happened in Surabaya, not just the fighting between British and Indonesians, but also the conflict between the old (colonialist)and new world (post-colonial Asia). This makes the development of Surabaya Inferno more unusual, as we bring out information often missing from books since Indian sources are less commonly used. Most research about the Battle of Surabaya relied on Indonesian sources but did not see how Indians viewed the Indonesian struggle in Surabaya.

Pre-Production and Production

Development of Surabaya Inferno started on 15 February 2020. We had previously thought of making the Battle of Surabaya as a first-person shooter, but since this was more challenging, we opted to make it as a real-time strategy game. With no budget, we made this game with a strong desire to adapt what we found in our research

We used Game Maker Studio 1.4 Standard, and project development only involved two team members: a composer and a game director who handled everything from programming and art to marketing. The development of Surabaya Inferno was divided into two phases, February-May and August-September. 15 February to early June was the first phase, where the production focus was on making 3 main scenarios for Surabaya Inferno and publishing them on Itch.io. The quality of Surabaya Inferno from the first phase was not as good in comparison to the second phase.

In the first Surabaya Inferno, our plan was for a first-person shooter, combined with strategy. This proved very difficult. We returned to a real-time strategy game, but with new features compared with other real-time strategy games developed by Sengkala, such as Perang Laut Maritime Warfare and The Last Great War of Mengkasar.

In the second phase, the game was published on Steam and released on20 September 2020, which made Surabaya Inferno Sengkala’s first game published on the Steam platform. We borrowed money to pay for Steam Direct in early August and marked the project’s further continuation as we made the first Sengkala page on Steam. We added new features to the game, like negotiation with Japanese soldiers, surrender, shooting enemy warplanes, and food supplies.

Post-Production

After releasing Surabaya Inferno, sales were very low but still better than on Itch.io. This is because Sengkala Dev made a mistake with our marketing, and a problem with the tutorial meant that players complained on the first day, which lowered the user score and made the game unpopular. It will take a year or maybe more to reach the minimum sales necessary to withdraw money from Steam, which means we are still unable to donate our game revenue share (10%) to veterans.

Many of the events of the Surabaya revolution are not shown in the game since we were confused about how to adapt them. This is an ongoing challenge that we need solve for our future Radio of Resistance project, which we will move on to once our Perang Laut-Maritime Warfare project is done. We learned a lot about game marketing and quality from the Surabaya Inferno case. The Radio of Resistance project is based on the Sutomo organization’s radio broadcasting, which was very important in igniting people’s spirit against colonialism. With this project, we hope that players can feel the revolution in Surabaya compared to the present. We plan to include extensive original work from Sengkala and increase the quality of the game as we have for Perang Laut-Maritime Warfare.

Sengala Dev is a small developer from Tangerang, Banten Province, Indonesia, focused on making historical games. Currently, the studio consists of Muhammad Abdul Karim, game director, and Raden Agung, composer, who creates the music for all of Sengkala’s games. Since 2015, Sengkala Dev have made several games from Pedalahusa Fall of Bali (January 2017, status on-hold), Surabaya Inferno (September 2020, released), Dato of Srivijaya (December 2020, released), and Perang Laut-Maritime Warfare (October 2021, currently under development and will be released shortly). You can find them on Twitter here.