By offering environments in which play can take place, games provide their players with resources from which they can craft their own narratives. In historical games this includes the capacity to create stories set in the spaces of the past, but players can be seen to engage in historical work in relation to a range of non-historical environments as well. Practices such as modding and archaeogaming, for example, have seen players apply historical sensibilities in games such as Arma 3 (2013)and No Man’s Sky (2016): games which are not typically considered to be historical games. In this post, I’m going to focus on one such player practice – that of cartography – and explore how the map-making activities of players across a variety of games can be thought of as historical work concerned (at least in part) with environments – spaces – of play.

Making Maps

Player cartography produces a wide range of materials of different kinds, with different purposes, but all connected with games. Mapmaking is a principal way that players articulate their relationship to the environment in which their play takes place – the gameworld, its places and spaces. Although many games provide maps – to play on, or of important game locations – player cartography is a longstanding part of game culture, both as a core part of gameplay (in the Etrian Odyssey series [2007-19], for example, or in map-making games like Ryuutama [2007]) and as an adjunct to or extension of play (mapping a game level to orientate yourself, for example, or creating new maps for Civilization 6 [2016]). Player maps might be produced digitally or on paper, by hand or by software, online or off. They capture, for players, critical aspects of the play environment, including its boundaries – be those the edges of a scenario map in a player-produced level, or gaps and spaces which represent the limits of exploration.

The examples I’ve just provided allude to some of the many ways in which maps are utilised by players in relation to their play. Such instrumental usage reflects established contemporary (Western) sensibilities around maps, which see them as tools to identify, explain and master space, and echoes longstanding colonial logics discussed in relation to historical games and roleplaying games alike. My own interest in these maps really begins, though, when their use value is exhausted – when they have stopped being tools and become something else: remnants of play, representing the afterlife of game experiences. Historical (re)sources, in other words, which textualise play and, most importantly for us here, play environments.

Player Cartography as History

As a practice which produces historical materials, player cartography is significant not only in the history of games, but in the development of historical cultures around games. When considered outside the narrow framing of utility, it is immediately apparent that maps can and do tell – and capture – stories, through an attention to location. This is a way of thinking about maps that, in the West at least, predates modern instrumentality – medieval maps, for example, focused on locations and events, serving as (usually spiritual) storytelling devices, as Thomas Rowland describes. For Rowland, this mode of mapping does not commonly survive in contemporary culture, but has experienced a renaissance in games, particularly in video games which represent story progression through non-geographical maps. This approach to understanding space can also be seen outside video games, of course, in maps such as those produced by players of adventure gamebooks.

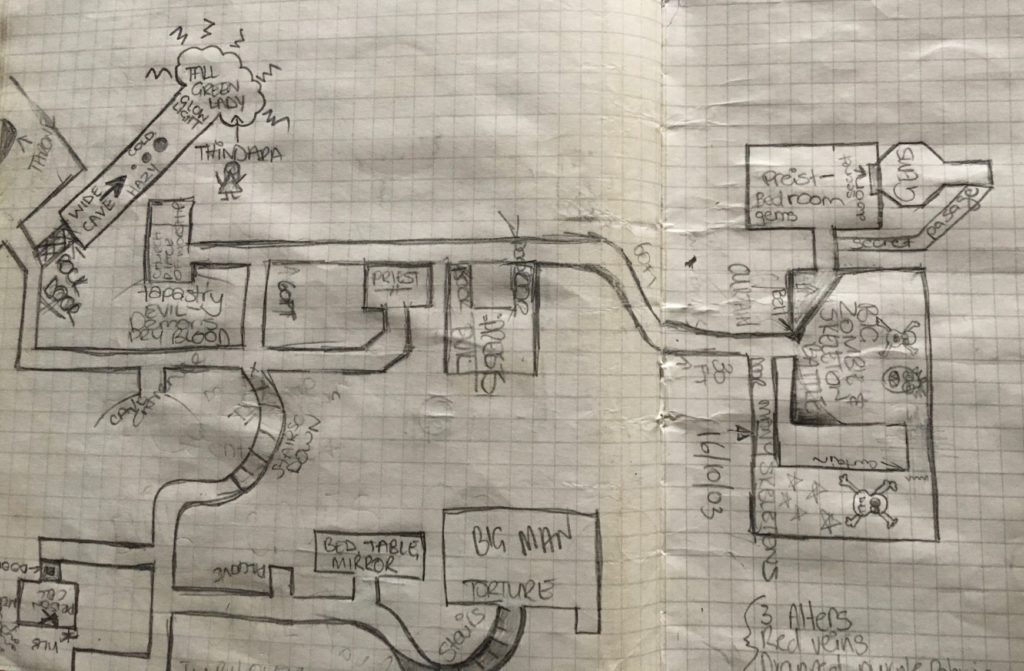

Player maps may also identify meaningful landmarks and include annotations by their creators to assist themselves – and others – in navigating a space and recalling the events which took place in a particular locale. As already suggested, their presences and absences imply a commentary on which parts of a gameworld were explored and what might have happened to the explorers. In his examination of ‘The Oldest Dungeon Maps in D&D History’, for example, game historian Daniel Boggs compares maps made during a playthrough of Blackmoor Dungeon c.1972 with the published version of that adventure, drawing our attention to the spaces missed and features of the environment which went undiscovered by the players. As Boggs goes on to demonstrate, these maps prompt memories of the experience of play, with map-maker David Megarry recalling:

We would be scrambling like mad to figure out a strategy. We would have been drawing the map by hand on loose graph paper. If the room was unusually hard to describe, [the gamemaster] would draw what we could see on our map. We never got to see his map.

Archival Environments

Significantly, also, where player maps exist beyond the immediacy of a game, they are amenable to archiving. In fact, it is through archives that some of the historical benefits of this player practice can perhaps best be understood, particularly when the maps that players make represent the only enduring reminder of their play: solitary mnemonic materials which evoke memories of places in games long since ended. Repositories which incorporate such maps configure player cartography clearly as a historical practice, whether they are personal archives which hold the gaming remnants of an individual life, or larger, more developed community spaces. Archiving not only preserves materials for future use and engagement, solidifying their historical value, but also allows stories to be told through comparison in cases where multiple maps are available – for example in each session of a roleplaying game or when different players have mapped the same play location.

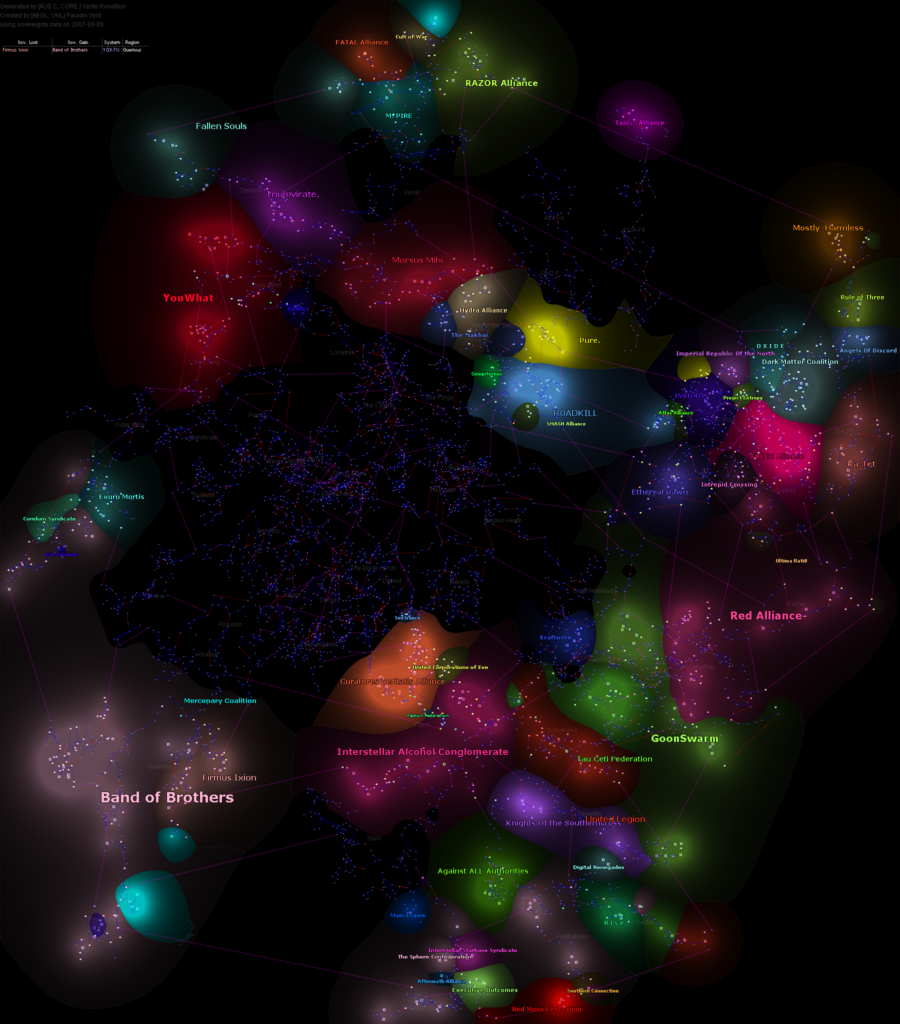

At an ordinary scale, such comparisons narrate the emergence of the play environment in the Dungeons & Dragons game Adventures in the World of Wearth, played in 2000-2 and recorded in a monthly campaign diary. Rather more grandly, the daily sovereignty maps produced by Verite Rendition trace the shape of the empires of New Eden, the star cluster setting for EVE Online (2003-date). These maps represent shifting allegiances, ownership of resources, and control of space, defining the environment of EVE’s nullsec. The map archive covers 15 years of activity by thousands of players, commencing on 9 August 2007 and running to date, like some vast, granular historical atlas.

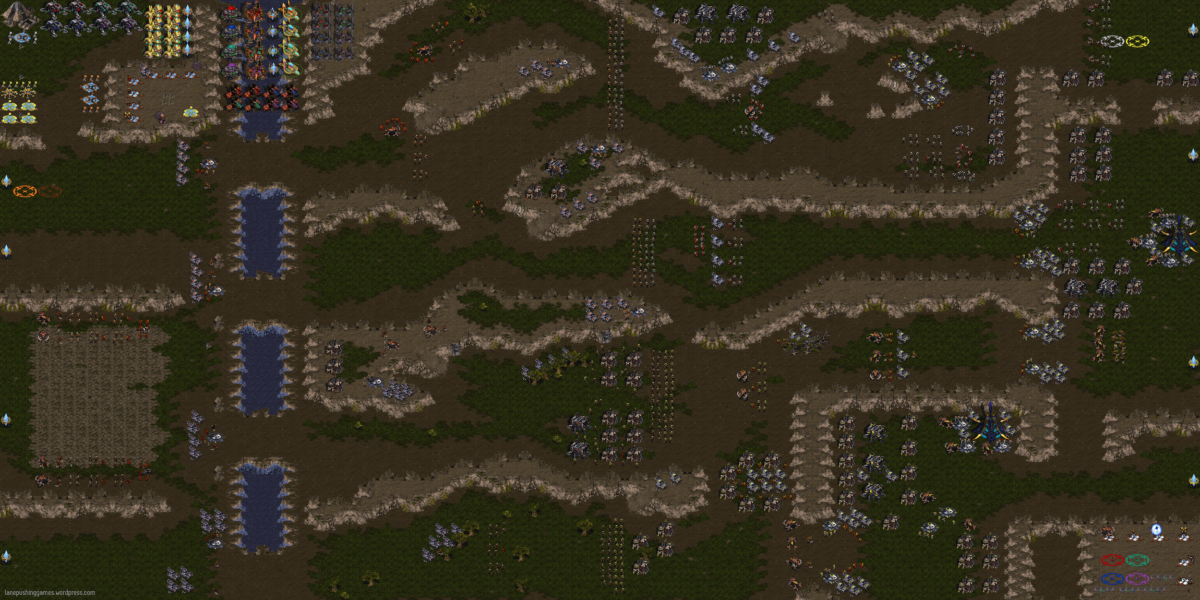

Similar, usually more modest, acts of community cartographic collection can be discovered for other games, focused variously on individual games, games series, game genres, etc. Player maps also, however, sit at the centre of non-cartographic projects which are concerned with the past of a range of games, particularly where their form either evokes shared memories of common experiences, or where such maps have been important or influential. One significant example might be the Starcraft: Brood War (1998) map ‘Aeon of Strife’, developed by player Nick Taijeron (Gunner_4_ever) in 2001-2. Popular with Starcraft and subsequently Warcraft III: Reign of Chaos (2002) players, this map offered a four-lane environment for play which spawned a raft of imitators. These included the original ‘Defense of the Ancients’ map, which played a key role in the development of the MOBA genre. As such, the Aeon of Strife map has been a key part of attempts to understand the past of MOBAs and related games, and to recover and archive maps that were part of this development.

The play environments which games offer, then, are historicised through the practice of player cartography, which captures them and makes them available for archiving. Here, map-making is historical work, conducted by players as part of and/or an extension to their play, in response to the spaces in which that play takes place.

0 replies on “Mapping Game Environments: Player Cartography as History”

muy interesante