Developed by Omega Force and published by Koei Tecmo, Bladestorm: The Hundred Years’ War (2007) is a tactical action game that immerses players in the brutal conflicts between England and France during the 14th and 15th centuries. The game is set during the Hundred Years’ War (1337–1453), which was a protracted conflict between England and France marked by shifting alliances, dynastic disputes, and the gradual evolution of medieval warfare (Seward 2003). This era saw the decline of chivalric combat in favor of more strategic and large-scale engagements, and in Bladestorm players take on the role of mercenaries who play a central role on the outcome of the war, reflecting the historical reality of the period (Janin & Carlson 2014). Players can take on the role of a mercenary commander who fights for either the English or French forces, which reflects the shifting loyalties and economic motivations that defined medieval warfare during this war (King & Ambuhl, 2024).

Unlike purely fantastical medieval-inspired games such as Dragon Age (2008), Bladestorm aims for a more grounded representation of medieval warfare, incorporating historical figures, battle formations, and the prominence of mercenaries in the period. While historical game studies have long grappled with the tensions between historical fidelity and creative license, particularly in medieval settings (Glancy, 2021), Bladestorm exemplifies a hybrid approach. Unlike games that fully embrace an imagined past, like Skyrim (Cooper, 2016) or Dragon Age (Jorgensen, 2010), Bladestorm integrates fantastical elements within a broadly historical framework. This balancing act reflects a broader trend in historical game design, where the incorporation of the fantastical—whether through mythic embellishments, anachronistic mechanics, or narrative liberties—serves to heighten engagement without wholly abandoning historical referents.

Although Bladestorm is more historically grounded than games like Skyrim or Dragon Age, it does not reach the meticulous ludic and experiential authenticity of games like Kingdom Come: Deliverance (2018), which emphasizes historical accuracy in combat mechanics, social structures, and daily life, or A Plague Tale: Innocence (2019), which carefully reconstructs 14th-century France’s social and environmental conditions while depicting the devastation of the Black Death and the Hundred Years War . This is not to say that Kingdom Come and A Plague Tale function as fully accurate simulators. Kingdom Come’s aesthetics, for instance, often prioritize visual and narrative coherence over strict historical fidelity, and its storytelling incorporates modern narrative sensibilities, particularly in its characterization and dialogue.

However, from a perspective that looks exclusively at game mechanics, Kingdom Come is more mimetic in its depiction of the medieval period. Its combat system, for example, eschews the exaggerated, cinematic action of many medieval-inspired games in favor of a weighty, physics-based model that emphasizes stamina management, directional strikes, and historical fencing techniques. Similarly, its survival mechanics—requiring players to eat, sleep, and maintain their equipment—reflect an attempt to immerse players in the material conditions of the era in a way that Bladestorm does not.

Instead, Bladestorm occupies a middle ground—it is historically inspired rather than strictly historical, offering enough realism to feel authentic to the average player while still taking creative liberties for the sake of gameplay. This balance between history and fiction is further disrupted in Bladestorm: Nightmare (2015), an expansion that introduces supernatural elements such as mythical creatures and fantastical battles, pulling the game away from its semi-authentic roots into the realm of medieval fantasy.

Like many games that depict the Middle Ages, Bladestorm blends historical elements with stylized gameplay, potentially shaping players’ perceptions of the medieval world. Still, while it captures certain aspects of medieval warfare with more realism than many fantasy-based titles, it ultimately distorts the historical record, reinforcing popular medievalist tropes that prioritize spectacle over historical nuance. This post will discuss the congruities and discrepancies between the historical fiction of Bladestorm and the historical fact of the Hundred Years’ War.

Bladestorm’s Political and Historical Shallows

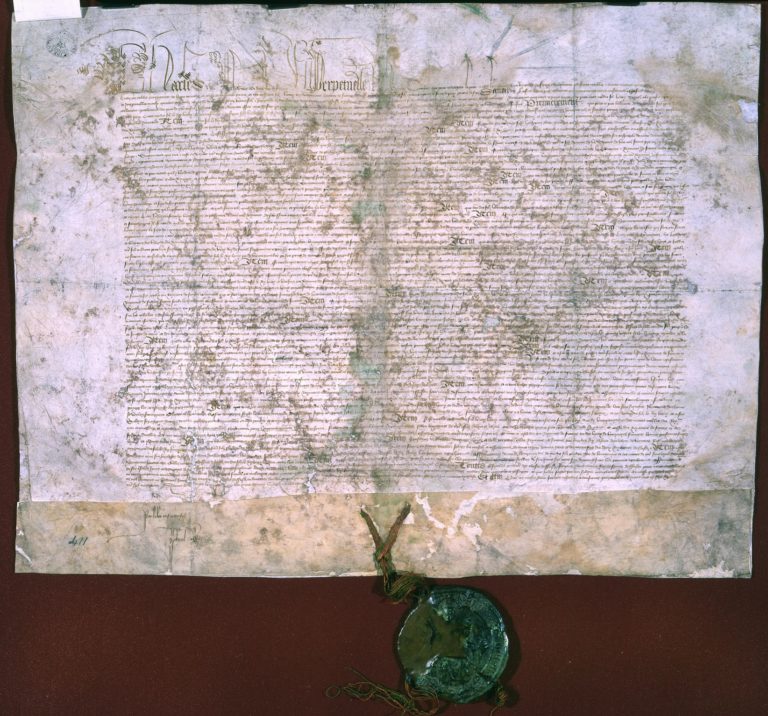

Although Bladestorm draws inspiration from real historical events, its portrayal of the conflict is heavily simplified, stripping away much of the political intricacy that defined the period. The Hundred Years’ War was not a straightforward battle between England and France but rather a multifaceted struggle involving fluctuating alliances, internal divisions, and competing claims to the French throne. Burgundy, for example, played a crucial role, at times siding with England against France (Mansoor & Murray 2016). Likewise, the war was influenced by broader political, economic, and social factors, including disputes over succession, shifting military strategies, and even the impact of the Black Death.

These elements are largely absent in Bladestorm, where the focus is on battlefield engagements rather than the underlying causes and consequences of the conflict. Bladestorm reduces these complexities to a binary opposition, presenting the war as a clear-cut clash between two nations rather than the tangled web of feudal allegiances and betrayals that it truly was. While Bladestorm does feature historical figures such as Joan of Arc and Edward the Black Prince, their portrayals lack the depth and complexity of their real-world counterparts. Joan of Arc, for instance, was not just a warrior but a deeply religious figure whose visions and leadership changed the course of the war. In the game, however, characters are often reduced to simplified archetypes—heroic leaders or ruthless warlords—rather than nuanced individuals shaped by their historical contexts.

By streamlining the war’s political and historical intricacies, Bladestorm prioritizes gameplay accessibility and dramatic storytelling over historical fidelity. While this approach makes the game more engaging for players, it also risks reinforcing a reductive understanding of the Hundred Years’ War, shaping perceptions of medieval warfare as a straightforward, nationalistic struggle rather than the complex and often chaotic reality it truly was. This is further exacerbated by the game’s romanticized depiction of medieval combat.

Anachronistically Heroic Mercenary Commanders

While Bladestorm takes inspiration from historical battles, its depiction of medieval warfare is heavily romanticized and emphasizes individual heroism and large-scale spectacle over the gritty realities of medieval combat. The game places the player in the role of a mercenary captain who can single-handedly influence the outcome of battles. While medieval commanders certainly played crucial roles, warfare in the Hundred Years’ War was driven by collective strategy, discipline, and coordination rather than lone warriors changing the tide of battle.

The game’s mechanics allow the player to seamlessly switch between different units, giving them a level of control that is far removed from historical reality. In actual medieval warfare, a single leader—especially a mercenary—would rarely, if ever, wield such overwhelming influence. Historical accounts depict mercenaries as operating within the constraints of feudal command structures, often negotiating with nobles for payment and authority rather than single-handedly directing large-scale battles (Usher, 2006).

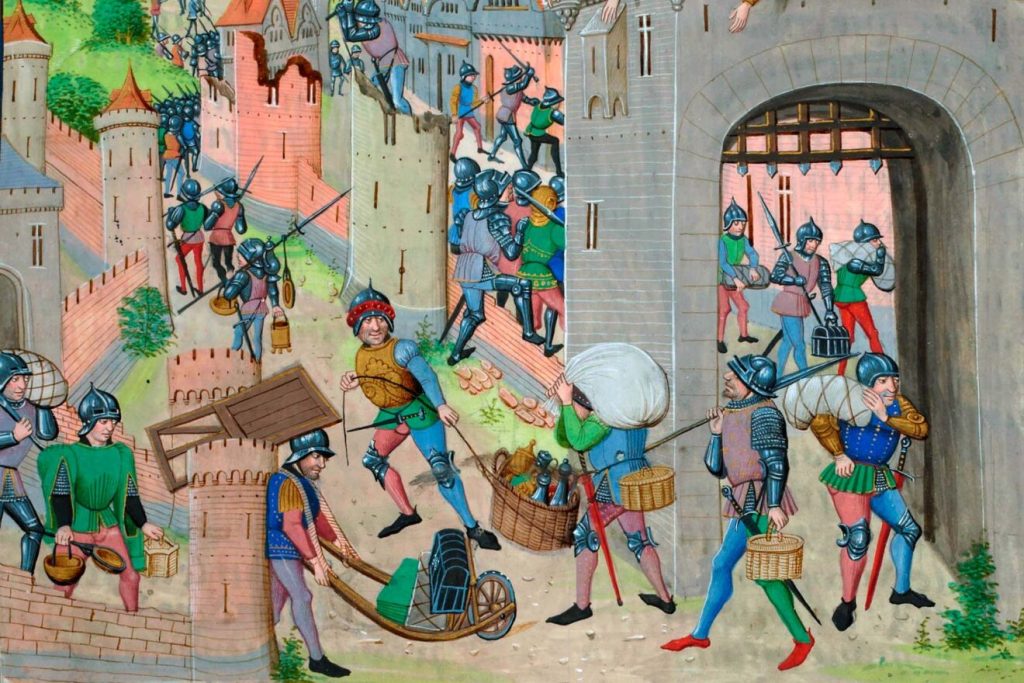

Additionally, medieval campaigns were not just about combat; they were deeply shaped by logistical concerns such as food supplies (Lambert, 2011), terrain navigation, and the seasonal constraints on warfare (Pryor, 2006). As John Keegan (2012) notes, the success of military campaigns often hinged on the ability to secure provisions and maintain supply lines, with armies frequently resorting to pillaging when resources ran low. Armies required extensive supply chains, and starvation or disease often claimed more lives than battle itself (Green, 2015). Bladestorm, however, largely omits these crucial aspects, presenting warfare as a series of dramatic engagements rather than a prolonged struggle of endurance and resource management.

Medieval warfare was not solely about soldiers clashing on the battlefield. Engineers, siege specialists, camp followers, and even clerics played essential roles in sustaining armies. Castles and fortifications were often besieged rather than assaulted outright. The realities of war in the Middle Ages included rampant disease, exhaustion, and psychological strain. Desertion, mutiny, and shifting morale were common, particularly among mercenaries, who often prioritized financial incentives over loyalty (Urban, 2006).

Bladestorm bypasses these elements, portraying soldiers as unwaveringly obedient and battle-ready, which simplifies the unpredictable nature of real medieval conflicts. It also reduces medieval warfare to open-field combat, neglecting the vital contributions of those who operated behind the scenes. While this approach makes for engaging gameplay, it risks perpetuating myths about medieval warfare as a purely heroic and straightforward endeavor.

Regressively Progressive Middle Ages

Another misconception that the game’s ludic and narrative exigencies might reinforce in players is, ironically, regarding the period’s ethos of innovation and how it contrasts with its rigid social structures.

The Hundred Years’ War was a period of significant military innovation, as it saw the introduction and refinement of pivotal technologies like the longbow, gunpowder weapons, and new siege tactics, which would fundamentally alter the nature of warfare (Pryor, 2006). The English longbow gave infantry a newfound power to defeat heavily armored knights, while the growing use of cannons and firearms began to shift the balance of power in siege warfare. Bladestorm, however, downplays these advancements and focuses on more conventional medieval combat, where knights and traditional melee weapons dominate the battlefield. As Houghton (2025) suggests, this approach not only limits the tactical depth of the game but also reinforces an outdated, “Dark Ages” myth that medieval technologically regressive.

Contrasting this technological march forward was a stagnant social ethos. The game introduces female mercenaries in prominent combat roles, which, while historically inaccurate for the period, offers a more inclusive and diverse gameplay experience. In reality, medieval warfare was overwhelmingly dominated by men; and although women had a lot more agency during this period than both medieval and contemporary fiction show (Cannon, 2019), when it came to warfare they were only occasionally involved in defense or in exceptional leadership roles and rarely participated directly in combat. This portrayal sidesteps the rigid social and gender hierarchies of medieval Europe where roles were strictly defined. The game makes mercenary life seem more egalitarian than it was, as medieval mercenaries were often drawn from specific social strata, with limited opportunities for people outside of certain classes to rise to prominence.

Closing Comments

In the end, Bladestorm: The Hundred Years’ War presents a compelling and engaging vision of medieval warfare, blending historical events with fictionalized elements to create an action-packed gaming experience. However, its portrayal of the Hundred Years’ War, while entertaining, is not entirely faithful to the complexities of the historical period. The game simplifies key aspects of the conflict, such as the political intricacies, the technological innovations, and the social realities of medieval Europe, opting instead for a more accessible and dramatic narrative that emphasizes individual heroism and combat. This approach leads to a romanticized version of medieval combat, which aligns more with outdated myths of the Middle Ages as a period of stagnation rather than a time of technological innovation and progress. While it does presents a more inclusive play experience by incorporating female mercenaries, this inclusion comes at the cost of ignoring the rigid social and gender structures that characterized medieval society.

Still, while Bladestorm may distort the player’s understanding of the historical Middle Ages, it serves as a reminder of the ways in which games can both shape and reflect our perceptions of history. As with many other historical games, the tension between historical accuracy and gameplay dynamics underscores the challenge of balancing entertainment with education, and the potential impact that these representations can have on how players view the past.

Johansen Quijano is an Associate Professor of English at Tarrant County College, where he teaches courses on rhetoric, literature, writing, and digital media. His interests lie at the intersection of rhetoric, theory, history, education, and games. Although his early work focused on gaming and language acquisition, his current focus is on games, rhetoric, and history. He has published in several anthologies and journals, participated in translation, adaptation, and creative videogame projects, and presented in local, national, and international conferences. His proudest playful achievements include winning several regional Dance Dance Revolution championships during the early 2000s and ranking as top player in the Samurai Shodown (2019) leaderboards for around 30 seconds. You can find him at @QuijanoPhD on YouTube, BlueSky, Instagram, X, and threads.

References

Cannon, Jonathan William. Women In The Age Of The Hundred Years War. 2019. Florida State University, Thesis.

Cooper, Victoria Elizabeth. Fantasies of the North: Medievalism and Identity in Skyrim. 2016. University of Leeds, Dissertation.

Glancy, John. “Creative Licence vs Historical Authority | Historical Games Network.” Historical Games Network, HGN, 19 May 2021, www.historicalgames.net/creative-licence-vs-historical-authority/. Accessed 16 Mar. 2025.

Green, Monica Helen. Pandemic Disease in the Medieval World : Rethinking the Black Death. Arc Medieval Press, 2015.

Houghton, Robert. “The Digital Dark Ages and the Trouble with Tech Trees | Historical Games Network.” Historical Games Network, 17 Dec. 2024, www.historicalgames.net/digital-dark-ages-tech-trees/. Accessed 21 Mar. 2025.

Janin, Hunt, and Ursula Carlson. Mercenaries in Medieval and Renaissance Europe. McFarland, 2014.

Jorgensen, Kristine. “Game Characters as Narrative Devices. A Comparative Analysis of Dragon Age: Origins and Mass Effect 2.” Eludamos: Journal for Computer Game Culture, vol. 4, no. 2, Nov. 2010, pp. 315–31.

Keegan, John. A History of Warfare. Vintage, 2012.

King, Andy, and Remy Ambuhl. Documenting Warfare. Boydell Press, 2024.

Lambert, Craig L. Shipping the Medieval Military : English Maritime Logistics in the Fourteenth Century. Woodbridge Boydell & Brewer, 2011.

Mansoor, Peter, and Williamson Murray. Grand Strategy and Military Alliances. Cambridge Cambridge University Press, 2016.

Pryor, John H. Logistics of Warfare in the Age of the Crusades. Ashgate Pub. Co, 2006.

Seward, Desmond. A Brief History of the Hundred Years War : The English in France, 1337-1453. Robinson, 2003.

Urban, William L. Medieval Mercenaries : The Business of War. Greenhill Books, 2006.