A few weeks back I was invited by a friend to attend a regency and renaissance dance class. Whilst I enjoy dance I admit I was mostly lured by the opportunity to cast myself for an afternoon as a romanticised heroine attending a ball in some BBC period drama adaptation – the BBC’s 1995 Pride and Prejudice adaptation to be precise, although the setting was to be less Netherfield Hall and more local community centre.

We began by standing in a circle stretching arms and legs and introducing ourselves. This week the focus would be on the Renaissance period, with dances from the 15th century. But before we started, the teacher paused and offered up a polite apology and clarification for those new to the class… that the steps of the dances that were to follow might differ from how others may teach or perform them.

In that moment, I was confronted by a very ‘oh, of course!’ realisation about historical dance. Their movements were never captured on video, nor was their choreography consistently passed down through generations. Instead their memory lay in notations, within which there is room for interpretation and misinterpretation. Everything we were about to perform that afternoon was a considered but contested attempt to recapture something embodied that lay just out of reach.

To play a videogame is also to perform. To each game a player brings skill, intention and a knowledge of the physical language required to operate a controller. That language is of course not static, it evolves. As technology progresses controller hardware changes, and so too do standard input formats, button combinations, meta games and playstyles.

Even if we were hypothetically able to resolve the many complexities of being able to preserve a playable game alongside what we might agree to define as its ‘original’ hardware, and invite someone to play it 1000 years from now, the way a player would approach that experience is different from how they would experience it today.

Just like those historical dances the physical performances of players can be a transient and fragile thing.

When is Bloodborne? Where is Bloodborne?

In my work as a videogame curator I create installations and displays that capture, interpret and communicate aspects of videogame design and culture to audiences. Looking at videogames through the lens of a performance is a critical part of this work.

computer based representation without the human participant is like the sound of a tree falling in the proverbial uninhabited forest

Laurel, B. (1991). Computers as Theatre 1st Edition. Pearson Education.

The holistic whole of what ‘a videogame’ is for me is inseparable from the intention of interaction. No videogame is an easily definable tangible material object that can be exhibited. They are instead the potential of an immeasurable number of performances, each uniquely defined and changed in response to the intervention of a player and the context of where and when they find themselves, each bringing different intentions, knowledge, and skills.

“When the itch to ask “What is [insert object]?” arises, we would do well to also ask “When” and “Where” is that object before we scratch too hard. “What is Space Invaders?” can be replaced with “When is Space Invaders?” and “Where is Space Invaders?””

Guinns, R. (2014). Game After: A Cultural Study of Video Game Afterlife. MIT Press

Capturing and conveying the fleeting physicality of a player’s performance was a core aspect of one particular multichannel installation exhibited as part of the 2018 V&A exhibition Videogames: Design, Play, Disrupt.

The installation focussed on Bloodborne (FromSoftware, 2015) a popular role playing action game set in the Victorian gothic inspired setting of Yarnham. Alongside the back catalogue of other FromSoftware titles it is a game notorious for its unrelenting difficulty, and as far as performances of videogames go, those elicited by Bloodborne are some of the most challenging to undertake.

Inspiration for the display came from the ways in which player communities had responded to the game’s challenges by supporting each other through the creation of video guides and tutorials shared on sites such as YouTube. Their videos documented fight sequences, play styles and combat, passing along tips, training and guidance.

In the installation we wanted to present a playstyle that felt like that of a ‘skilled average player’. Whilst the type of performance we aspired to present might appear simple there were a lot of factors to consider…

…the fight needed to be successful, it can’t be too short or last too long, it needed to demonstrate key moves and modes of combat, the choice of weapons used and dress of the player character shouldn’t be too niche, the camera should be angled and moved in a way that creates an optimal viewing experience for a spectator…

The brief needed a choreographer and performer, for which we collaborated with game critic, YouTuber and skilled Bloodborne player Matt Lees.

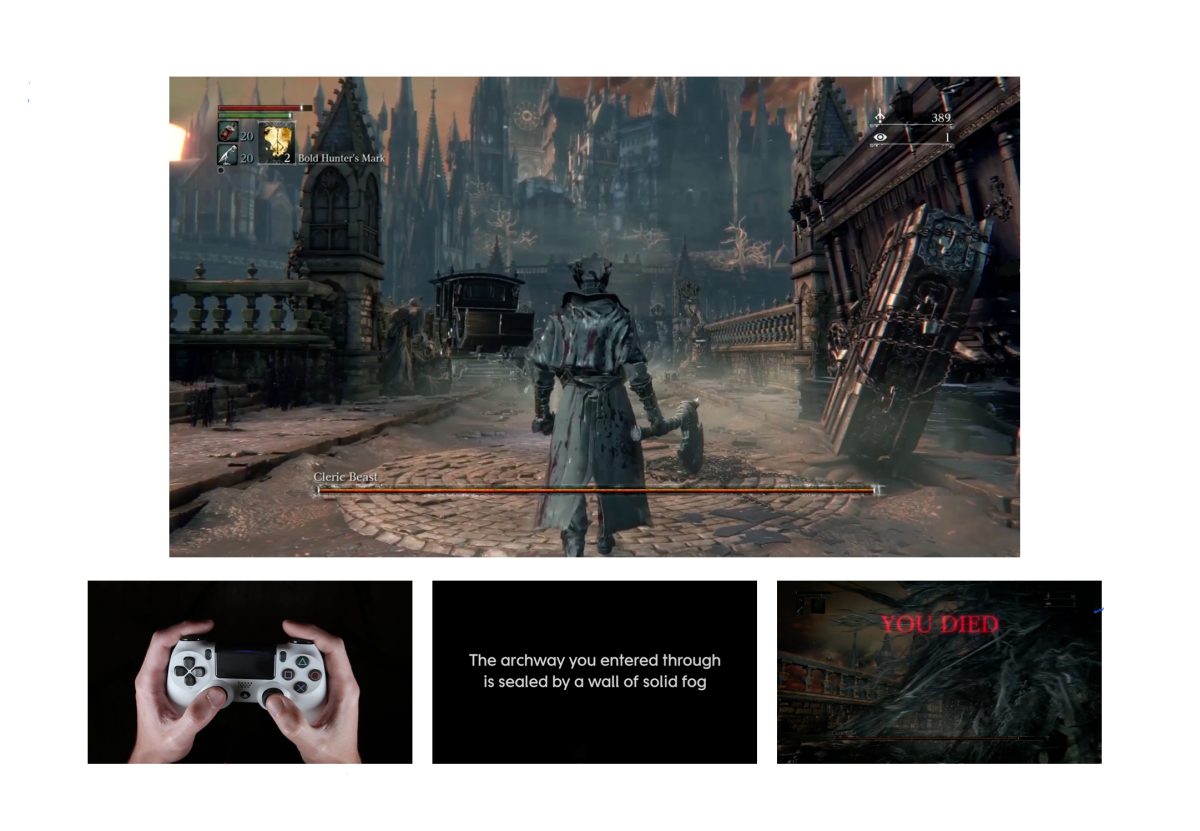

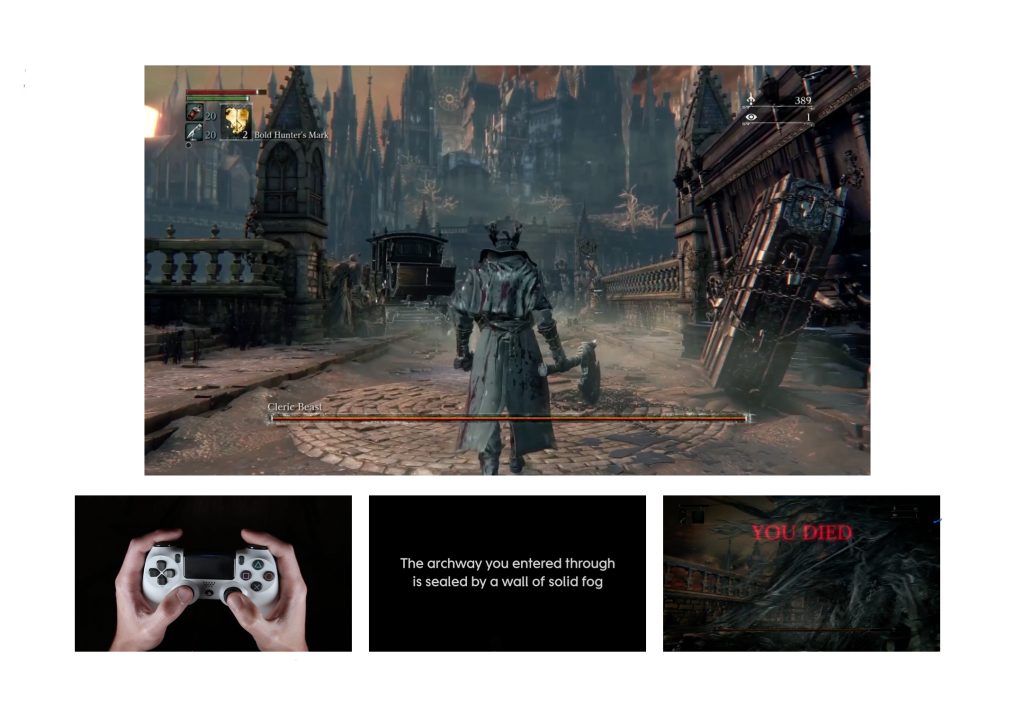

The resulting installation consisted of four synchronised video screens arranged in a formation similar to a religious triptych, echoing the game’s gothic setting. Each screen presented a different perspective on just one fight sequence, that of the Cleric Beast.

The largest screen of the installation, situated at the top of the display, featured a screen recording of Matt successfully battling and defeating the Cleric Beast. Accompanying this sequence was a dramatic commentary scripted and performed by Matt breaking down the sequence, discussing the game’s design and his responses to it as a player.

Contrasting the success of that main sequence the bottom right screen displayed a montage of failed attempts to take on the Cleric Beast, each preceded by the game’s infamous ‘You Died’ message.

The bottom central screen displayed animated subtitles of the scripted commentary so as not to obscure the game’s UI overlay.

Lastly, but by no means least, in the bottom left screen was a synchronised recording of Matt’s hands on the controller during the fight. Set against a black backdrop his brightly lit hands grip the controller and his fingers and thumbs skip across buttons, D pads, triggers and thumb sticks, moving in coordinated and almost rhythmic sequences.

I’m proud of the installation we created for the game. It was well received in the exhibition, it was successful in capturing a specific type of Bloodborne performance that communicated a significant aspect of the game’s design, and it was a display format fitting for the ‘V&A exhibition’ context it was shown within. But I’m also aware of its limitations as a recording in truly engaging with the physicality and ‘life’ present in Matt or any player’s performance.

Keeping Bloodborne Alive

“As I think about the variable media art in the Berkeley Art Museum/Pacific Film Archive collection, I ask, “Do we want to preserve this art or keep it alive?” The former approach treats a work of variable media like a musical recording, locking in time some masterful performance. The latter approach treats the work more as a musical score, the same piece open to future iterations.”

Rinehart, R (2003). Permanence Through Change: The Variable Media Approach. Berkeley Art Museum/Pacific Film Archive

In 2019, a year after the exhibition closed, I was in New York reflecting on the exhibition and researching ways other museums had approached similar challenges in displaying and collecting complex ephemeral mediums. It was here, in a conversation with Athena Holbrook, a collections specialist in MoMA’s performance department, where her work provided an inspiring provocation that has stayed with me.

In particular she spoke of the museum’ s 2015 acquisition of Simone Forti’s Dance Constructions (1960-61), a series of performances that are part sculpture and part “dances based around ordinary movement, chance, and simple objects like rope and plywood boards”.1

To bring the work into the collection a constellation of materials were acquired: videos, sketches, photos, notebooks, recorded interviews. Whilst the lived performances themselves could not literally be captured, collectively these materials alluded to the holistic whole of the dances.

In addition to those materials though is what the department referred to as ‘body to body’ transmission, a term that expresses an awareness that there is an essential physical and live aspect to the dances for which people are indispensable. For Dance Constructions this came in the form of regular workshops in which teachers pass along the dances to future generations of performers.

Athena herself travelled to document one such workshop with the intent of capturing the ways in which subsequent performances of the work would inevitably evolve. At this workshop she was herself invited to perform.

“In stepping into the role of performer (…) these performances have become part of my physical memory. I am both archivist and archive, documentarian and documented.”

Wagley, C (2018). How MoMA Rewrote the Rules to Collect Chroegrapher Simone Forti’s Convention Defying Dance Construcitons. MoMA.

As Athena notes, through learning these performances she herself has transcended the line between curator and object, which for me is a beautiful and powerful provocation for how we might consider the ways in which we exhibit and archive videogames.

What would it mean to not simply record a player like Matt playing Bloodborne, but to acknowledge and value that he and that skill have the capacity to be part of a living installation or archive that is not just supplemental to a game, but is an intrinsic part of it, and one which can be passed down from person to person across generations.

I cast my mind forward to 1000 years from now. A group of people gather in the local community centre on Mars. They sit in a circle around a large screen, stretching their fingers and thumbs as they introduce themselves to each other. Today, the teacher informs, they will be performing Bloodborne, a game from the 20th century…

Marie Foulston is a leading curator behind exhibitions, installations and experiences that specialise in videogames, play and digital culture. She is co-founder and creative director of Good Afternoon, an experiential design creative agency. Previously she was Curator of Videogames at the V&A where she lead the curation of the headline exhibition ‘Videogames’, was guest director of experimental games festival ‘Now Play This’ at Somerset House and co-founded the UK alternative videogame collective the Wild Rumpus. Across her career she has worked alongside a host of international organisations and leading cultural institutions including the Smithsonian, ACMI, PlayStation, the Design Museum, Netflix, Channel 4 and Nintendo.

- Lim, N (2016). MoMA Collects Simone Forti’s Dance Constructions. MoMA ↩︎