Earlier this year, we at the HGN were very fortunate to work alongside several other partners, including historian Dr Chris Kempshall, the University of Glasgow Games and Gaming Lab, and sponsored by World of Tanks to co-host the Imperial War Museum’s War Games Jam.

The War Games Jam asked participating teams to create an innovative war video game inspired by IWM’s collections and stories of conflict from 1914 to the present. We hoped that participants would create games or gaming concepts which featured unexpected and under-explored stories of conflict, embracing creativity, empathy and diversity in their design and challenging expectations of what video games based around war and conflict can be (and all the teams certainly delivered this!). Each video game was inspired by one of several specially-selected IWM collection items from the First World War onwards. The War Games Jam formed part of IWM’s War Games season and all the submissions are available to play here.

The IWM team were fantastic and encouraged two types of competition entry: one for Best Playable Game and the other for Best Game Concept. In each category the competition was incredibly close – the judges’ scores attest to the closest of contests. “Phantom of the Battlefield” came runner up in the Best Concept judging category, and was designed by Leif Gay, Michael Ghose, Gwydion Hir, Ryan Holman, and Adam Weinstein, all MA History Students at Cardiff University. They have written the following post, reflecting on their process.

Our team was composed of several different students with various historical areas of interest, who all attend the Cardiff MA History course. We all volunteered to participate following an email from Esther Wright, as we all shared an interest in the history and evolution of Video Games.

Target Audience

Our main goal was to create a game for mature audiences over the age of twenty. We wanted to focus on the people who would play games such as This War of Mine (2014), Life is Strange (2015), or Valiant Hearts (2014). These games provided emotional experiences akin to books or movies, and we aimed for an audience which appreciated the cinematic nature of video games. Just like these games, our focus was to create a compelling game experience rather than one that needed to be fun. Furthermore, these games were aimed at an older audience as a means to encourage intergenerational conversation about wartime stories, thus making the game an act of community creation.

Ideation Process

Multiple ideas floated through the group before selecting our chosen idea. These ideas included a horror game centered around the horrendous nature of warfare, and another game in which the player would play an engineer working on Spitfires. Eventually, we chose to pursue a concept inspired by the prosthetic mask.

Following on from the successes of grittier and more realistic games, such as This War of Mine, we aimed to create an evocative piece that would appeal to a more serious audience, as opposed to the traditional escapist games. We decided to take inspiration from narrative and character driven games, such as Mass Effect (2007-) and Red Dead Redemption (2010-2018), to provide an interactive experience that would aim to express the values of empathy, understanding, and charity.

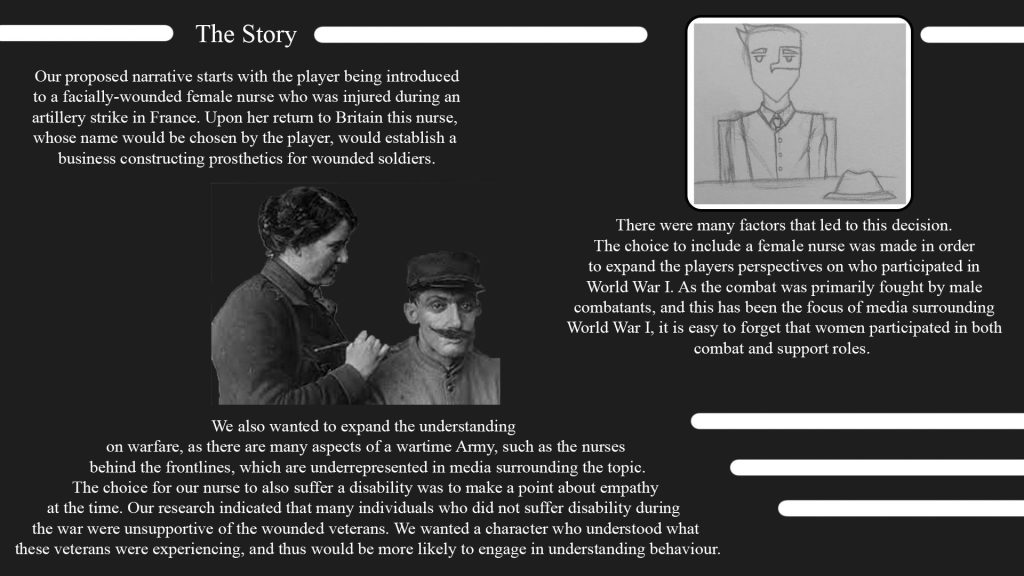

We decided to expand on our personal experiences either being associated with the military or with the struggles of mental health. Given the mental health crisis gripping men across the Western world, we expanded upon the idea of exploring the impact that physical disability from combat would have on a veteran’s mental health.

Historiography

The relevant historiography for our study is, to a certain extent, divided between the work of social historians studying twentieth-century society, and the specific studies of masculinity in war by gender historians. The former body of literature follows various themes. Most notably, the notions of “mental-health” and “emotion”, central to any exploration of the manifestation of trauma as a result of war, have been the subject of study in several works of Caroline Alexander (2007) and Andrew Bamji (1996), and are prominent concerns of Suzannah Biernoff (2011) and Katherine Feo (2007) in their studies of “shell-shock” in the First World War. “Self-actualisation” is also a central concept in the literature on the perception of soldiers after the war. This study has focused on the propagandization of the First World War and, by extension, the rhetoric of disfigurement in wartime communities. We have drawn especially from Jacob Benjamin Newton’s (2013) study of facial disfigurement, the understanding of which is a key methodological concern in this article.

Those emotional dimensions expand earlier works of Historical games scholarship – most notably, Adam Chapman’s (2016), whose methodological and theoretical framework can offer an answer to the well critiqued trap of representation. At the core of this visceral, conceptual approach is a special focus on (i) the collaborative environment that game developers should operate in and (ii) the role of the “developer-historian” (Chapman, 2016) who must occupy a diminished role in favor of emphasizing authenticity. It is an impassioned plea for a paradigm shift in the way we portray the experience of disfigurement, its many victims, and the institutional systems that supported the reintegration of veterans into society.

Aims

Our aim was to explore the impact war had upon the mental health of World War One veterans. These themes have been deeply explored in other media which are not as participatory as video games, but we wished to create an experience where the player could better understand the impact of “shell-shock” on both the veteran and the people surrounding him. This would also be one of the first times a game that centered on WWI was not focused entirely on combat. Instead of creating a fun first-person shooter simply set in the era, we aimed to explore the deep psychological impact endured by British communities. Within that complex web of social relations lies artwork that focused on the impact that WWI had on the individual, instead of the broader ramifications that led to WWI.

Given the broader debates surrounding masculinity and identity, we aimed to explore this in our idea. Our game would analyze the impact that being wounded had on a man, but also how war in general was connected to the masculinity of the era. We aimed for this to be a reflective piece on the masculinity of today, and how one should be empathetic to the struggles faced by young men with their mental health.

Inspiration

With the rise of games in which violence is not the primary focus, particularly in war-related video games such as Papers, Please (2014), we wanted to create a game that further delved into the emotional/traumatic aspects of war. Masks are synonymous with not only theater and the expression of emotion, but also with prosthetics and the desire to appear “normal” (whether they are physical or social). Masculinity, and the crises surrounding it, was at the heart of our motivations. We were drawn to exploring what remained of a man and his masculinity when physical parts of him were no longer there.

We also wanted to portray the consequences of war, rather than the active violence during World War I, and were inspired by the less glorious realities of service. Heroism is heavily romanticized in contemporary media, especially relating to both world wars by Britain, creating a glamorous illusion to cover the tragic consequences of conflict such as bodily disfigurement and PTSD.

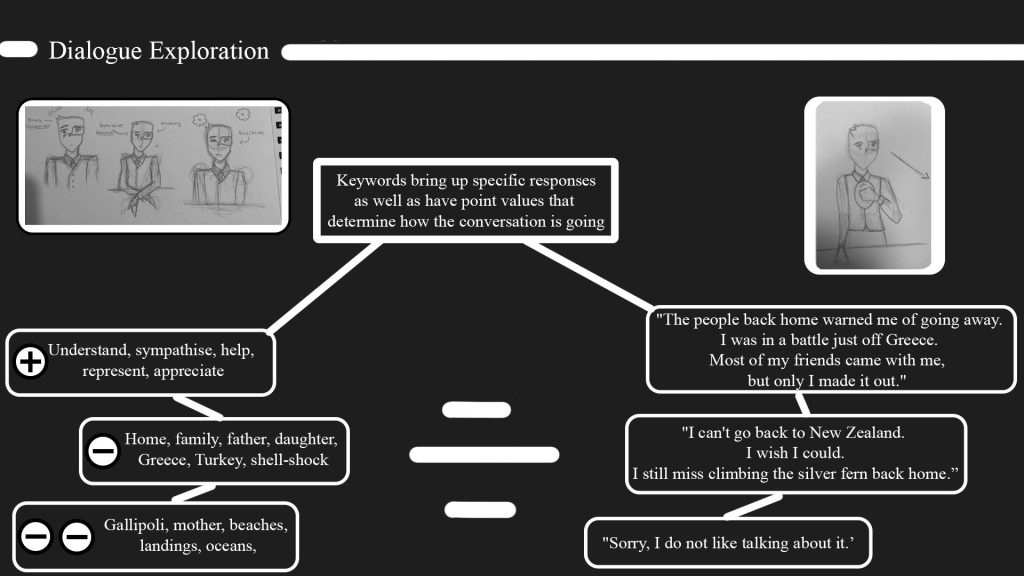

Choice, and the lack thereof, as a core narrative mechanic also inspired us. When the autonomy to choose is given to the player, particularly when it has an effect on the outcome of non-playable characters, it facilitates a bond between them and the realities of the game world. In essence, they become invested through empathy and a sense of responsibility to improve the life of their patient. Games featuring heavy consequences as a result of player choice such as the Mass Effect series and Life is Strange, as well as games with an emphasis on the human experience such as L. A. Noire (2011).

With regards to art style, our concept artist was particularly inspired by Valiant Hearts for its dynamic and readable art style as well as its focus on creating a compelling experience for the player.

The prosthetic itself was based on not only the exhibition piece, but also visual media depictions of facial disfigurements and prosthetics, such as in Amsterdam and Boardwalk Empire.

Roles

Our roles were divided based on our interests and skills. Michael and Ryan were both interested in exploring the renegotiation of British citizenship during the Great War and were thus in charge of research. Their work provided authenticity to the concept, and allowed us to accurately shape our ideas to fit the experiences and perceptions of the wounded veteran.

Leif, who is a skilled artist, was in charge of creating the concept art for the project. They took inspiration from the art styles of Valiant Hearts and other games to create a stylised example of how our game could look.

Gwydion, given his experience growing up within a military family and the Air Training Core, was made the creative director. Gwydion created the ideas from which the game was further developed by the other members of the team. Gwydion further developed the game and helped other members with their work.

Finally, Adam was in charge of the project given his in depth experience with game design. Adam conducted a significant portion of the administration, organizing when we would meet, making documents, etc. Adam further refined the ideas to take our concepts and make them into practical mechanics that could be present in a game.

(From Left to Right: Gwydion Hir, Leif Gay, Michael Ghose, Ryan Holman, Adam Weinstein).

Conceptualization process and overview of game

- Concept synopsis

- Player is making a facial prosthetic for a wounded soldier

- Soldier gradually opens up about his life and his experiences in the war

- How we went from an idea seeing the objects and ended up following up developing this into a concept.

- Issues we had with development (lack of research conduct on veterans with ww1 and how they were or were not able to reintegrate with society)

- Development of concept art where the inspiration for the style and imagery came for the emotions and ideas that these are trying to convey

- Empathy as a game mechanic

- Trigger words

- Modern day counseling techniques

- Highlighting how mental health can be a very pressing issue that continues into this day – mainly men & veterans

United in our passion for gaming, we are a group with eclectic historical interests. Featuring three modern historians, an early modernist and even a medievalist we had a wide range of expertise to employ. As such, our roles and contributions reflected not only our scholarly interests but also our own life experiences. It was because of this approach that we turned our perceived disadvantage into one of our greatest strengths.

Ultimately, we wish that we could have done even more. Oftentimes our group desired to expand the concept with more storylines and features (such as more artwork) that were not feasible within our given timeframe. Hindsight brought with it the feeling of what small improvements could be applied if the game were to make it beyond the initial concept phase. But overall, our struggles with time constraints forced us to be more focused and concise with our ideas.

Final Project

We were awarded first place for creativity and second place overall. We were pleased with the outcome, as we were primarily aiming to create something new and unique that reflected our passions for history.

Ultimately, we all feel that we achieved our aims. Our game focused on the experiences of warfare beyond what is currently marketable, and provided a more nuanced and empathetic approach to a war that changed the world. We are all proud of our work, and grateful to have had the chance to work together on this project.

Reflection

Gwydion: “It was a fantastic experience, and I’m glad to have had the chance to take part in an interesting competition with a brilliant group of people.”

Adam: “Working on this project and with this team was an amazing experience. To me, it was what game jams are really about, bringing people of various disciplines together and letting them try their hands at thinking and creating games. I’m proud to have spearheaded the project, but none of it would have been possible without how wonderful the team was. Even though we were runner up, to me, our project flourished even better than any of us anticipated and I wouldn’t change a thing about it. My only hope would be that we can turn it from concept to game later down the line.”

Ryan: “As our research has suggested, anxieties about the consequences of wartime injury and the integration of soldiers into communities intersected with concurrent concerns about the hierarchical, social and gendered standards of society. The experiences of facially disfigured veterans also shows how savoir faire, having the capacity to take the appropriate action, was crucial to reintegrate into society and avoid societal discrimination.”

Leif: “It was amazing to combine two of my favourite hobbies (art and gaming) with history! And even more so to work alongside students studying different historical disciplines. I am deeply proud of our project and am so grateful to have had the opportunity to participate. I highly recommend students, whether they are historians or artists, to broaden their horizons by taking part in events such as this.”

Michael: “Looking back on this game concept I can appreciate the collaborative process of digital-game creation which can open up spaces for community engagement. The game successfully looks at the reality of post-war veterans to cast light on the functioning of national processes and state power. I think that we were able to highlight how veterans with facial disfigurement were perceived differently from those with other disfigurements. Here, those who had facial disfigurements were seen as ‘monsters’ but those who had other types of disfigurement- such as losing a limb- were seen as heroes. It is this peculiar middling status, halfway between the nation and the wartime community, that allowed us to create a game through the lens of mask-makers in Great Britain. In this way, the creator of facial prosthetics humanized those with facial disfigurement by seeing the player predominantly interact with them throughout the game. It is this ‘way of seeing’ that shone a light on an underrepresented wartime history which was replicated through fictionalized characters rooted in our extensive historical research.”

Bibliography

- Alexander, Caroline. Faces of War. February 2007. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/faces-of-war-145799854/ [accessed 18 February 2023].

- Bamji, Andrew. “Facial Surgery: The patient’s experience.” Facing Armageddon: The First World War experience. Ed. H. Cecil and P.H. Liddle. London: Leo Cooper, 1996. 495.

- BBC. Inside Out: Shell Shock. 4 March 2004. https://www.bbc.co.uk/insideout/extra/series-1/shell_shocked.shtml [accessed 19 February 2023].

- Biernoff Suzannah. “The Rhetoric of Disfigurement in First World War Britain.” Social History of Medicine 24 (2011): 670.

- Bourke, Joanna. Dismembering the Male: Men’s Bodies, Britain and the Great War. London: Reaktion, 1996.

- Chapman, Adam. Digital Games as History: How Videogames Represent the Past and Offer Access to Historical Practice. Oxfordshire: Routledge, 2016.

- Feo, Katherine. “Invisibility: Memory, Masks and Masculinities in the Great War.” Journal of Design History 20 (2007): 19.

- Glubb, John. Into Battle: A Soldier’s Diary of the Great War. London: Cassell, 1978.

- Gullace, Nicoletta. The Blood of Our Sons: Men, Women, and the Renegotiation of British Citizenship During the Great War. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002.

- Muir, Ward. The Happy Hospital. Kent: Simpkin, 1918.

- Newton, Jacob Benjamin. “Facial Disfigurement in Post World War 1 Britain: Representation, Politics, and Masculinity, 1918-1922.” Historical Perspectives: Santa Clara University Undergraduate Journal of History 18 (2013): 139-164.