From the classic ‘super shotgun’ of DOOM 2 (1994) to the non-lethal ‘Portal gun’ from the game series (2007-2022) of the same name, the gun is an important piece of technology represented in countless games and one of the primary means by which the video game player interacts with their world. Famously, it has spawned whole genres of games under the umbrella “shoot ‘em up” and later, simply “shooter”. Those more familiar than I with the relevant academic literature can perhaps comment upon the extent to which this emerged from the existing fascination with the firearm as a killing tool (especially in movies and TV) and a desire to replicate that act in a harmless environment, versus the need for a simple way for the player to project their intent and actions into a virtual world.

However, despite the pioneering game Pong (1972), relatively few best-selling games depict the use of a table-tennis bat/paddle, so I suspect that the power fantasy and ‘cool’ aspects figure pretty strongly here. In any case, this is a boon to me as a firearms curator and historian because, along with other media depictions, it sparks a great deal of interest in my own area of expertise and in the collection of technological objects – guns – for which I am responsible.

Despite 15 years of occasional documentary appearances and enquiries from the film and TV industry and even public talks on topics as exciting as vampire slaying kits, by far my most successful public engagement has been on the GameSpot YouTube series ‘Firearms Expert Reacts’ from 2020 to 2024. Over four years and 200 episodes, I analysed depictions of firearms and their usage in a wide range of video games from the last 20 or so years. These were mostly first and third-person shooters but even a few real-time strategy games and on one memorable occasion, the ‘casual’/‘party’ game Splatoon 2 (2017)! This, coupled with more decades than I care to think about playing video games myself and 15 years studying and shooting firearms, has given me an unusual level of insight into how and why guns have been depicted to varying degrees of verisimilitude in computer and video games.

Initially, I followed the typical ‘Expert Reacts’ path of straightforward critique. In most videos the subject matter specialist applies their real world knowledge to the virtual depiction presented to them – compare and contrast. In my case, the cocking handle on that rifle is in the wrong place, the cartridge cases are ejecting from the wrong side, the name of that gun is made up – that sort of thing. I think this follows naturally from the premise, and as far as it goes is fine. An ‘expert’ is there to tell you things that you don’t already know, and even if they are personally interested in (or like myself, consumers of!) pop culture depictions of their subject, there is always a measure of professional distance, especially if representing a public institution.

Like good comedy, a good ‘reaction’ video thrives on incongruity and the subverting of expectations. It clashes academia with pop culture, deliberately (if not always consciously) holding the unreal to the impossible standard of the real, or at least to what Pötzsch termed “selective realism”.[1] For the content creator, this amusing juxtaposition gleans views and income. For the participant, it’s an opportunity to educate. They seek to address specific popular misconceptions, to make viewers aware of the likely inspirations behind their favourite media, to persuade that verisimilitude is worth striving for, and of course to promote their own research and/or institution.

Most experts only get one or two ‘shots’ (sorry) at appearing in such videos, so they focus on what’s ‘wrong’ with a given depiction. That’s fine as far as it goes – people are curious to know how close a piece of media gets to being ‘correct’, and those looking to see a film director or game studio knocked down a peg or two will enjoy such criticism. As another museum curator who featured in one of these videos discovered, though, when engaging with other specialists – in this case avid gamers – we run the risk of merely pointing out why someone’s favourite game sucks over and over again.

This risk increases dramatically over the course of a weekly series like ours, to the point of the same guns coming up and a feeling of being something of a stuck record on certain errors and tropes. On the plus side, I always tried to moderate and caveat my criticism to spare the poor artists and animators (often under tremendous external pressure) from blushes, and some really did enjoy just this aspect – several developers took my comments as the constructive feedback that they were intended as, and some even made changes to their game as a result. This fed into the consultancy service that we offer and resulted in more studios visiting to achieve a higher degree of accuracy in models, textures, animations and depicted capabilities. However, we couldn’t sustain a whole series of ‘reaction’ videos on ‘rivet-counting’.

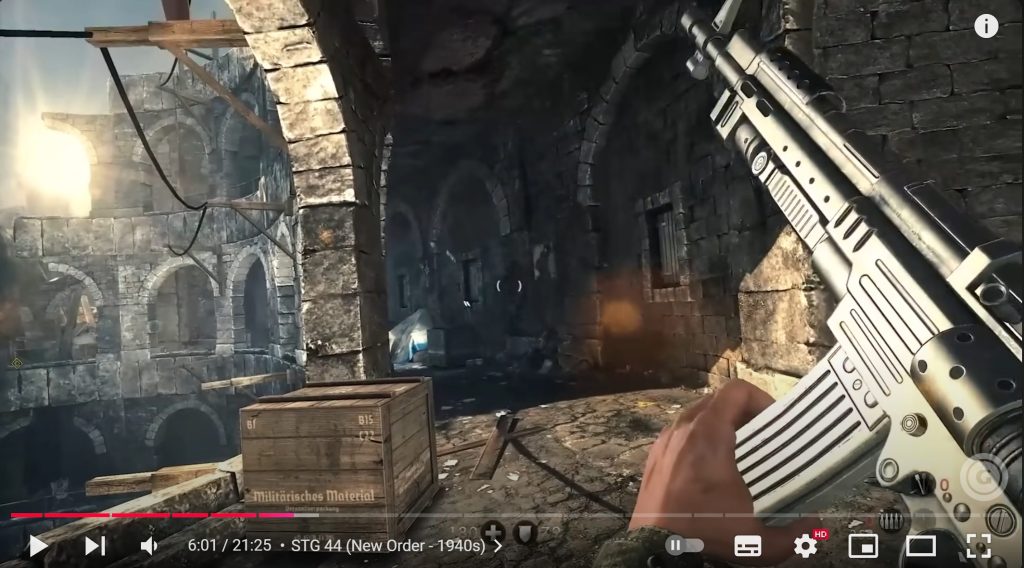

Fortunately the producers understood this and introduced more and more unusual games and guns. I might go from making a straightforward comparison of an M1 Garand from Hell Let Loose (2021) with a real example, to a sort of functional realism assessment (could this thing really work?) of sci-fi weapons from the alt-history Wolfenstein series (1981 to date), to essentially a design appraisal of pure fantasy weapons in the Destiny series (2014 to date). This turned the series from a potentially stuffy griping session to a celebration of ‘the gun’ in video games, whether intended to look and function as a ‘real’ piece of technology, or technology as an expression of art and design.

Even the outlandish-looking (and functioning!) so-called ‘cursed’ guns enabled what I felt was a more ‘relatable’ form of negativity that I think was more palatable to the audience and certainly more entertaining. Whether the mechanically impossible but creative Borderlands 2 (2012) gun that screams as it’s being fired, or the income-driven but strikingly designed ‘legendary’ guns of more recent Call of Duty games (such as this year’s Black Ops 6 entry), because these virtual weapons were intended to subvert conventional firearms design, it was possible to criticise or even visibly despair of them, while acknowledging the skill and creativity that had gone into their design, and the undoubted fun of using them.

The perpetual touchstone for me was to look for historical or other real-world parallels. I would point out design cues or run off to grab a real gun to wave in front of my webcam in reaction to the virtual version in front of me. Even the wildest weapons often had some relation to the real world, and thus relevance to my expertise and to the Royal Armouries collection. This, of course, was ours and my primary reason for taking part.

The series began during the COVID-19 pandemic, when the public could not visit our museums and we struggled for digital content to maintain some level of engagement. This series not only gave us unprecedented engagement but allowed us to direct a huge audience to our own YouTube channel (which went from 37,000 subscribers to 350,000), to our social media accounts, our website and, after the final lockdown lifted, back to our museums once again. Beyond ‘historical accuracy’ or unattainable realism, the greatest hope of curators like me is to see viewers, especially the younger generation and new audiences, engage with the subject, to expand an existing interest or even to take an interest for the first time. Some of these viewers seek out more digital outputs from the ‘expert’ or their institution, perhaps even read in-depth articles, buy books, or even be moved to visit a museum thousands of miles away.

I have been very fortunate to see a lot of this in response to the videos that I appeared in for GameSpot, and will be forever grateful to their former producers – Dave Jewitt, Adam Mason and Chris Morris – who did so much to promote the Royal Armouries, the collection, and the work that we do. I was already aware of the contemporary relevance and potential for new audiences that engaging with video games could offer, but it took a global pandemic to realise that potential.

I will continue to devote a chunk of my working week to this kind of engagement work, and will work with my colleagues here to try to reflect this aspect of arms and armour as a subject within the galleries. Way back in 2012 I curated a ‘pop-up’ exhibition of video game guns, and it is high time that we did something similar again. Failing that, it is being factored into our long-term masterplan for the redevelopment of the Leeds galleries. There will be challenges, notably the lack of the physical 3D objects that we typically require as a museum, although we do have one prop pistol from Assassin’s Creed: Syndicate (2015). 3D-printed assets are a promising avenue, alongside audiovisual display aids, and of course real weapons and armour which have parallels to those in games, or which even served as direct inspiration for them, such as the ‘EOKA’ pistol from Rust (2013). On the income-generation side, this series has attracted more developers and artists to make use of our consultancy services, something that will hopefully continue as we become increasingly recognised as the ‘go-to’ for those seeking that selective realism in their work.

Jonathan Ferguson is Keeper of Firearms & Artillery, based at the Royal Armouries Museum in Leeds. His publications include the book ‘Mauser “Broomhandle” Pistol’ (2017), a contribution to ‘The Right to Bear Arms: Historical Perspectives and the Debate on the Second Amendment’ (2018), and ‘Thorneycroft to SA80: British Bullpup Firearms 1901 – 2020’ (2020). He has published several articles including ‘Trusty Bess’: the Definitive Origins and History of the term “Brown Bess” (2017) and (with Terence Smith) “One in the breech, five in the magazine”: British Aircrew Armament of the First World War, ARMAX Vol. VIII No.I (2022). Jonathan has curated several exhibitions including ‘Firefight: Second World War’ (2020) and ‘Re:Loaded’ (2023). He has also made several media appearances, including the History Channel’s ‘Sean Bean on Waterloo’ (2015), ‘Cunk on Earth’ (2022) and ‘Killing Sherlock: Lucy Worsley on the Case of Conan Doyle’ (2023). Since 2020 he has also appeared regularly on YouTube, notably the Royal Armouries’ own channel and Gamespot’s ‘Expert Reacts’ and ‘Loadout’ series.

[1] Holger Pötzsch, ‘Selective Realism: Filtering Experiences of War and Violence in First- and Third-Person Shooters’, Games and Culture, vol. 12, Issue 2, 156 – 178, First Published May 31, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412015587802